Originally produced on April 23, 2018 for Mauldin Economics, LLC

By George Friedman and Ekaterina Zolotova

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, which governed Uzbekistan as a satellite state, the country had had only one ruler: Islam Karimov, a strong-armed, unapologetically clannish dictator. He died in 2016 and was replaced by Shavkat Mirziyoyev. Shortly thereafter, Mirziyoyev announced reforms meant to open the country up to the outside world economically. He cultivated ties with potential patrons, including Russia, Europe, and China. More important, he began to improve relations with other Central Asian states. Cross-border disputes related to access and usage of energy and water resources are gradually being solved.

Today, Uzbekistan has all the appearances of a country on the rise. It is prosperous and stable by the standards of the region. But appearances can be deceptive. Beneficial though Mirziyoyev’s reforms might be, their uses are merely counterfeit. The cool logic behind them is that they help Mirziyoyev consolidate power and endear him to his subjects. In a place such as Uzbekistan, the tactics a leader use may be liberal or draconian, but the outcome is the same: Uzbekistan is not going to be anything other than a centralized state where the president has great power.

Evaluating the Reforms

What has the liberalization of Uzbekistan accomplished? Economic prosperity? Not really. The structure of the economy is largely the same as it has always been, dependent as it is on materials and extractive industries and on the countries that buy their wares. Inflation is still high and unemployment artificially low, as millions go abroad for work. The state is still active in the financial sector.

The end of strongman rule? Not so fast. Yes, some of Karimov’s opponents have been released from prison and their power curbed. Yes, the National Security Service, which unofficially controlled all spheres of life under Karimov, has been neutered, and its leader, Rustam Inoyatov, has been dismissed. Yes, purges in the defense and finance ministries have rid the system of Karimov acolytes. But the system, which remains vertical and top-heavy, is still largely intact. Mirziyoyev himself was prime minister before he was president. As prime minister, he practiced the same kind of authoritarianism Karimov did and eschewed the same kind of liberal reforms he purports to pursue now. And now that he is president, he faces the very same situation his predecessor did: He must achieve internal political stability from within and ensure security from without. He can only do that if he stays in power, and he can only stay in power if he wins the support of the people.

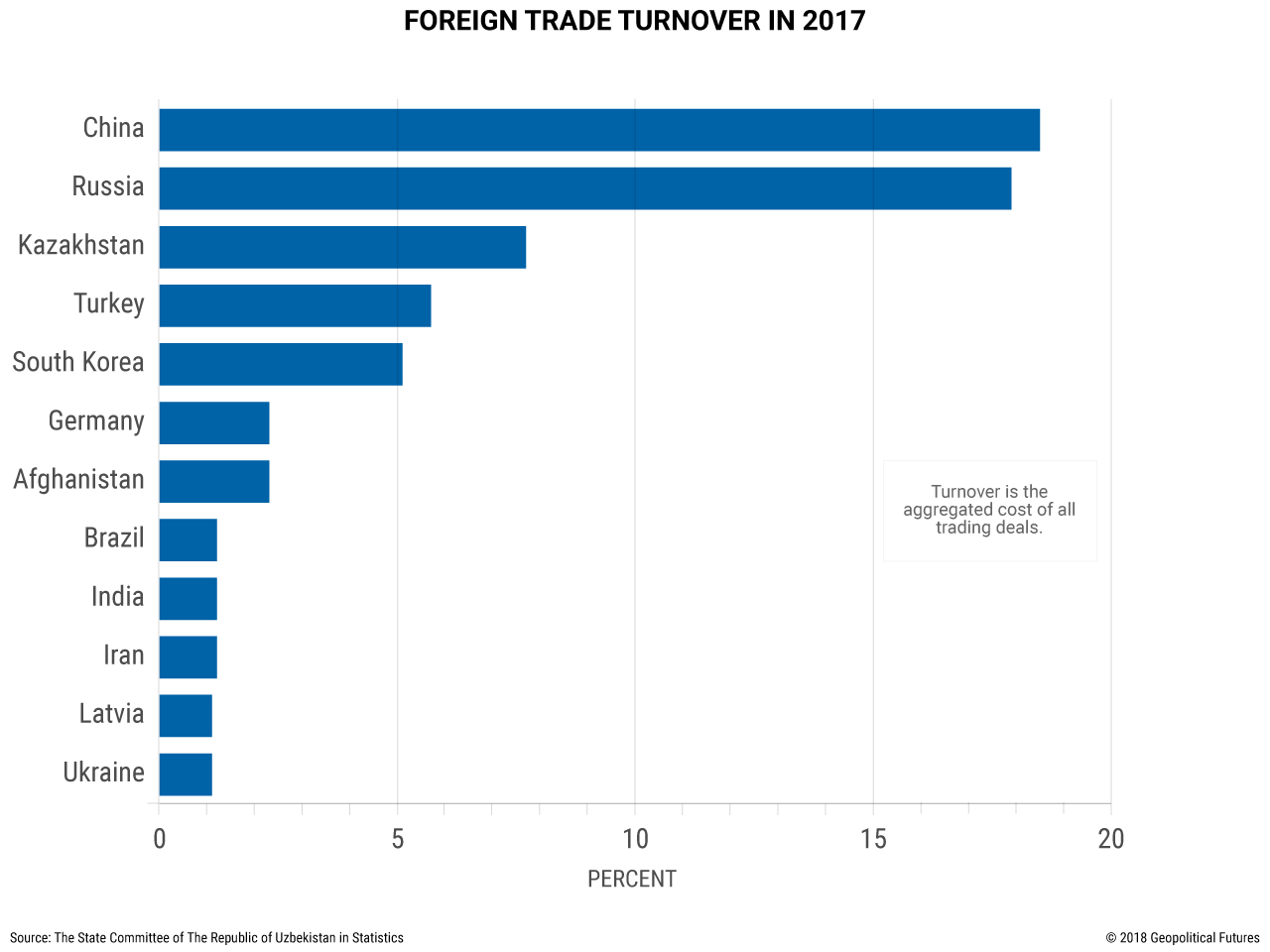

Did liberalization open up the country to external markets? In theory, yes. In practice, no. Mirziyoyev does support trade. He visits the countries with which Uzbekistan trades, provides platforms for solving problems, participates in organizations such as the Commonwealth of Independent States, signs bilateral agreements, and reduces transit fees. But these practices precede him. In fact, Uzbekistan has a long tradition of trade. Like all Central Asian countries, Uzbekistan has no access to the sea but has nonetheless been a major trading center since antiquity. Trade created some opportunities for Uzbekistan, but it also created dependencies on its neighbors and on existing trade routes. China accounts for nearly 19% of Uzbek trade; Russia nearly 18%; Kazakhstan roughly 8%; and Turkey some 6%. These dependencies prevent the government in Tashkent from entering new markets.

Karimov diversified his country’s trade partners as best he could, careful not to rely too much on any one country. Central Asia, after all, is a region in which the interests of East and West overlap. Uzbekistan in particular has recently been courted by countries in the Middle East, including the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, Iran, and Saudi Arabia. Uzbekistan values neutrality above all else and so is careful to find a balance among all its suitors.

Mirziyoyev is following in his predecessor’s footsteps. Having strengthened ties with China and Russia under Karimov, the government under Mirziyoyev has sought to expand contacts with partners such as India, South Korea, and the European Union in an attempt to diversify partners and, more important for his landlocked country, build new transport corridors to other, preferably Western, markets. To that end, Mirziyoyev has already made some changes to convince the world it is high time to invest in Uzbekistan. Government officials have invited several Turkish investors, who were previously expelled from Uzbekistan, back to the country. They have signed contracts with US companies for $2.6 billion, they have come to an agreement on financial cooperation with Germany, and they continue to look for more markets. This is all well and good for Uzbekistan, but it is not especially new.

Cozying Up to Russia?

Has liberalization improved relations within the region? Yes and no. It’s no secret that under Karimov relations with the rest of Central Asia were tense and that Mirziyoyev inherited a number of Karimov’s problems in that regard. There have been territorial disputes, disputes over access to resources, and personal animosities among leaders. The president has indeed endeavored to resolve some of these issues. But his decision to make nice with the region is less of a paradigmatic shift and more of a pragmatic decision. His country is in a precarious position. It is not receiving as much money from Russia as it once was, thanks in part to Russia’s own financial woes. China is viewed with apprehension. Uzbekistan may be able to forsake one but it cannot afford to forsake both. Solidarity among its neighbors helps dampen the blow.

The final question is: Has Uzbekistan under Mirziyoyev cozied up to Russia? The answer is yes, but only for now, and not because of anything Mirziyoyev has done. The reorientation began under Karimov, who, having rebuked the West when he removed a US air base from his country, repaired relations by reorienting trade and investment to Western states, mainly the US, and to South Korea and Japan. He was, in fact, the first Central Asian leader to spurn Russia. But relations between Uzbekistan and the West soured in 2005 when the Uzbek government killed hundreds of protesters (or thousands, depending on the source) in Andijan province. (The West condemned the government and levied sanctions against it.) Without a partner to turn to, Uzbekistan had to turn back to Russia to avoid total international isolation.

Since then, Russia and Uzbekistan have agreed to implement a variety of joint projects worth more than $15 billion. They have also discussed the possibility of increasing trade ties. Russia already buys agricultural products and foodstuffs from Uzbekistan, and Uzbekistan suspended excises on a wide variety of Russian goods.

None of this is to say that Uzbekistan is set to become a full and faithful Russian ally. Uzbekistan’s loyalty is notoriously hard to secure. Russia is buying less natural gas from Central Asia than it once did. And Tashkent still hasn’t joined the Collective Security Treaty Organization or the Eurasian Economic Union.

Mirziyoyev’s reforms are less radical than they appear. He faces the same challenges Karimov did and he has largely responded to them as Karimov did. There is little to compel him to create the institutions necessary for liberal democracy. There are no real steps to develop the institutions necessary for a market economy. The only real reform has been the purge of the National Security Service—the main competitor to the government. The reforms in the financial sector and taxation are aimed at improving the business climate in the country and attracting foreign investments to Uzbekistan, not at opening up to new and better markets. Flashes of liberalization are not the same as fundamental, systemic changes.