Mexico is one of only two places in the world (the other is off the coast of Peru and Ecuador) that resides on or near the junctions of four tectonic plates. This makes the country a hub for seismic activity, the cause of Mexico’s many mountain ranges and plateaus. The mountainous topography separates the country into regions with unique physical environments. In some areas this hindered the development of population centers, and it has defined the culture as well as which economic activities are viable.

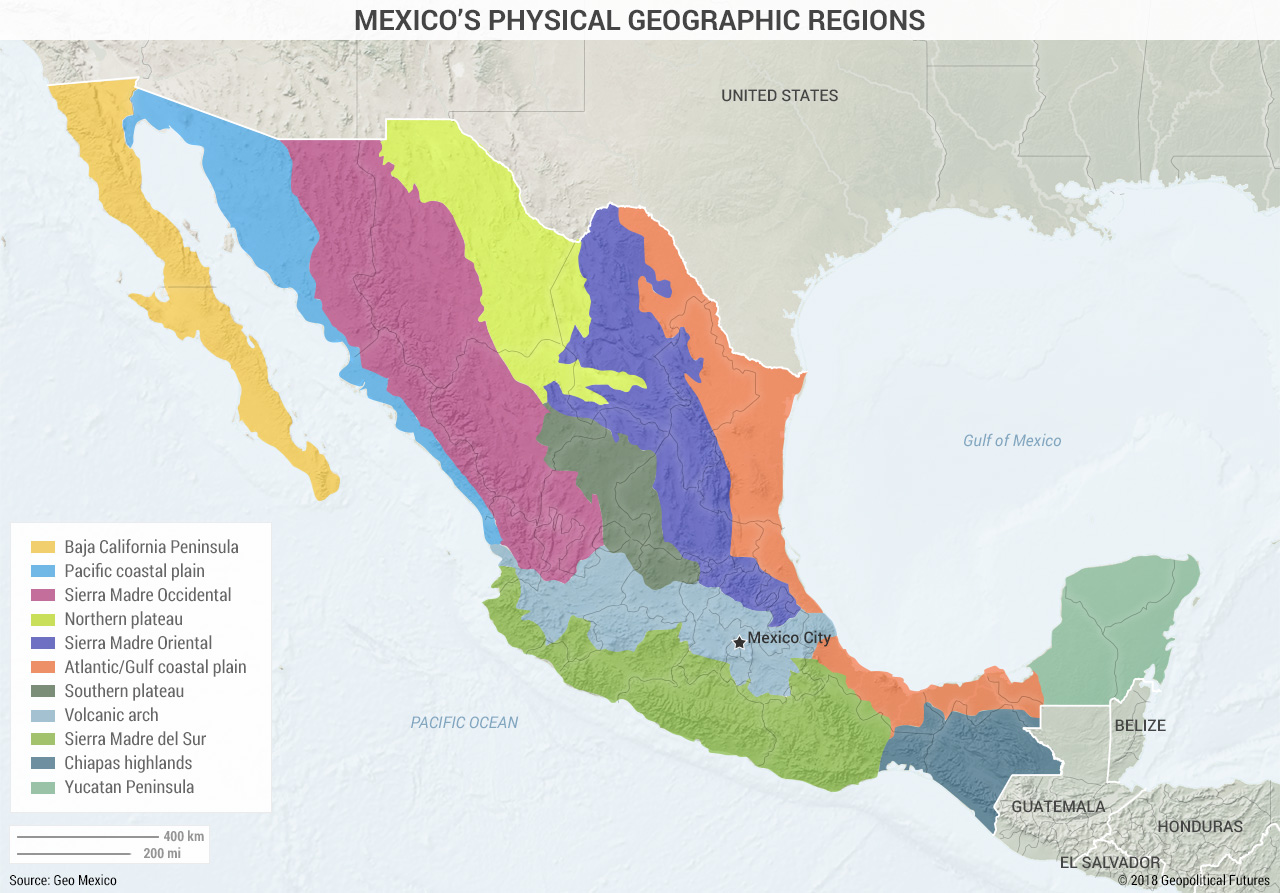

Narrow coastal plains and basins run along either side of the country. To the extreme northwest and southeast are the Baja California and Yucatan peninsulas, respectively. Just a short distance inland, three mountain ranges flank the mainland – the Sierra Madre Occidental in the west, the Sierra Madre Oriental in the east, and the Sierra Madre del Sur in the south. Between the western and eastern mountain ranges is the massive Mexican plateau.

Geographically, the Mexican plateau is a single feature; geopolitically, there’s a clear division between the northern and southern plateau regions. The Chihuahaun Desert dominates the northern plateau. It does not easily support large-scale vegetation, wildlife or human populations. The southern plateau, on the other hand, sits at an altitude 3,000 feet (900 meters), which gives it a much more habitable climate, and its valleys to the south are among the most habitable in the country.

Put these factors together and it makes sense why the valley south of the southern plateau region is the heart of Mexican civilization – the center of the Aztec Empire and still the geopolitical heartland of the country today. Nearly 500 years have elapsed since the Aztec Empire fell, but the situation isn’t all that different for Mexico today. Technology has reduced geography’s impact, but rarely does innovation overcome geography entirely. The mountains and long distances that afflicted the ancient empires of the land are still making it hard for the government in the valleys off the southern plateau to have a strong presence in Mexico’s peninsulas, coastal regions and northernmost states.

Mexico’s topography poses the same challenges to internal security that it does to central governance. Historically, Mexico City could not easily move large numbers of troops over vast distances and treacherous terrain, so it has had no choice but to rely on local forces to augment the national security forces. The Mexican states, in turn, have been conditioned to be self-reliant on security. From time to time, the isolation of some areas and subsequent feeling of alienation has engendered the creation of armed rebel groups hoping to secede from or even overthrow the national government. Combined, these trends have led to a strong belief in homegrown security and skepticism of the national government. This strongly influences the way the state and non-state actors respond to lapses in security in modern Mexico. Where geography and estrangement once fostered rebellion and independence movements, today those factors help explain the rapid growth of organized crime groups and the vigilante groups that have popped up to stop them.