The wars in Syria and Iraq have been drawing in great powers. They have become a pivot in the general crisis of Eurasia that Geopolitical Futures has discussed in detail. At the center of the crisis is the Islamic State and the question of what it is and how much strength it actually has. Many people have been trying to place IS in previous, known categories. But it doesn’t fit into any of these. It differs in one fundamental sense. It has taken and held substantial territories and has managed to hold on to them, administering them, maintaining an economy, extracting taxes, and governing under an authority satisfactory to its rulers and some of its followers, if to few others. Most important perhaps, it has shown itself able to defend the territory it has taken. IS has shown it can be brutal to the people living under its rule, and also engages in terrorism, as we saw recently in Paris, when it deems necessary. However, it is a mistake to see IS as primarily a terrorist group. Thus far, that has been ancillary to their identity. IS is a new state and, in this, it has done something that hasn’t been done in this region in almost a century. It has redrawn the region’s borders, carving two other states, Syria and Iraq, into very new shapes. Many have tried to dismiss the significance of IS, pointing to the fact that they have recently retreated from some areas. Reading media reports in recent weeks, one might get the impression that IS is about to collapse upon itself. These reports say thousands of IS fighters have been killed by U.S., Russian, French and now British airstrikes. U.S.-backed rebels have taken over 200 villages from IS control. Stories of IS defectors and refugees fleeing IS territory abound. However, we believe the retreats are not as significant as they appear, nor do they pose an existential crisis for IS. Whatever may happen in the future, IS at the moment is not trivial.

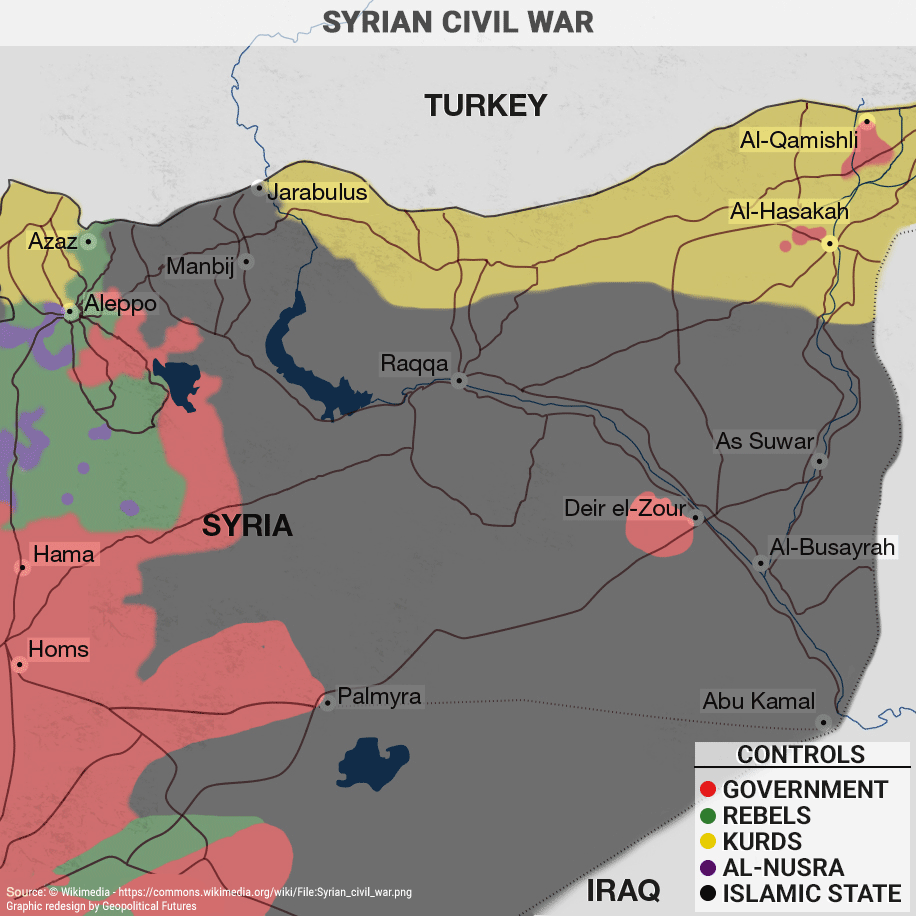

Looking at a map tells a more accurate story than news reports. The lands over which IS exerts direct political control amount to roughly 50,000 square kilometers (19,500 square miles) – similar to the size of West Virginia or Croatia. When one takes into account the sparsely populated deserts and other areas where IS can operate with relative freedom, even though it is not directly in control, this territory expands to approximately 250,000 kilometers (155,000 miles), roughly the size of Great Britain.

IS’ core territory is the stretch of land from Raqqa to Deir el-Zour in eastern Syria. Most maps of IS territory are confusing because they show that the group controls a huge swath of eastern Syria but most of this territory is desert. IS actually controls a narrow strip of territory in eastern Syria on both sides of the fertile banks of the Euphrates River. This territory is surrounded by rocky desert, which makes it difficult terrain upon which to stage an attack. IS then is a very thin river state anchored by Raqqa and Deir el-Zour. The most recent Syrian census done in 2004 estimated that close to half a million people live in the two cities alone. This is the area that IS must defend at all costs. Any analysis of the group must begin by seeing the world from Raqqa’s perspective.

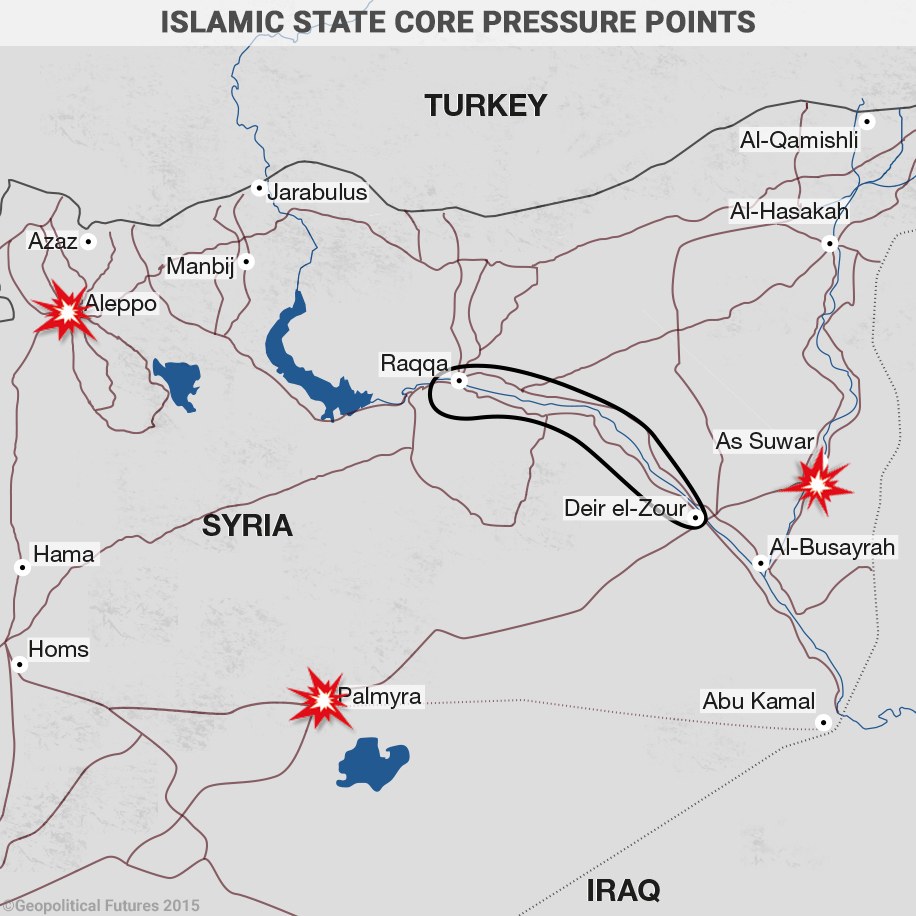

Keeping this in mind, the map begins to reveal some facts. This core region has four key vulnerabilities. The first and most appealing to an enemy would be to drive south from al-Hasakah to al-Busayrah. Rather than attacking Deir el-Zour directly, the goal would be to cut Islamic State in half, effectively making it very difficult for IS fighters to move in and out of Syria and Iraq at will. If an army or militia could hold this area, it could begin to contemplate an assault on Deir el-Zour or focus on blocking IS from moving to and from Iraq. Cut the Islamic State off here and Raqqa and Deir el-Zour will wither. The second vulnerability is to the southwest and its target is similar to the al-Hasakah approach. Advancing from Homs to Palmyra, forces could drive east with the aim of cutting Islamic State’s core off from Iraq. The third vulnerability is from Aleppo and Hama, both of which could serve as staging grounds for a direct assault on Raqqa itself. The fourth is from north of Raqqa in Tal Abyad city on the Turkish border, also a potential staging ground for an assault on Raqqa.

These are only potential areas from which attacks can be launched – for such assaults to come to fruition, forces with both the will and capability to attack IS in this fashion would need to be readied. Most of the rebel groups and militias in Syria are not interested in conquering the Islamic State or its territory, but rather want to advance against the Bashar al-Assad regime or carve out their own statelets. Turkey is the most significant anti-IS force that could operate in the region, but right now Turkey does not have any real skin in the game in the form of ground forces that could attack IS. This may change eventually, but until it does, IS will remain just as capable as all the enemies that are attacking it on the ground, if not more so.

Islamic State Deployments

Looking at the world from Raqqa’s perspective, IS’ deployments on its periphery make a great deal of sense. Palmyra was not just an opportunity to destroy ancient Roman ruins – it is a critical point that IS must hold in order to prevent an army from moving east to cut IS off from Iraq. The group has a firm hold on Palmyra and is skirmishing with Assad’s forces outside the nearby city of Homs. In November, the two sides traded control over the town of Mheen southwest of Homs, with Assad regime forces currently in control. To the northwest, IS is actively involved in the continuing battle for Aleppo. It is less important for IS to control Aleppo than it is for them to prevent Syrian rebels actively hostile towards IS from controlling the city. Therefore, IS is maintaining forces in this region and, when opportunities present themselves, the group carries out attacks, as it did on Dec. 3 against rebel forces when it took the neighborhoods of Kafra and Jarez, taking advantage of recent Russian airstrikes against rebel forces. Aleppo is being fought over by Syrian Kurds (via the YPG), Syrian rebel groups, including the FSA and Jabhat al-Nusra, and the Assad regime – IS has to maintain enough manpower in the region to help continue to complicate the situation.

As long as the Aleppo battle remains a de facto stalemate, IS will not need to worry too much about the Turkish and American plans to establish a 60-kilometer (37-mile) IS-free zone on the Turkish border from Azaz to Jarabulus. Azaz is too close to the mayhem happening around Aleppo for any one of the militias to attack IS positions, let alone to drive IS back over a distance of 60 kilometers. Furthermore, these rebels have very little incentive, if any at all, to go after IS. Aleppo and Damascus are worth way more than Raqqa and Deir el-Zour to them. To the east, there have been reports and rumors of YPG forces preparing to attack Jarabulus, but IS is in a relatively good defensive position in Jarabulus. The YPG can carry out night raids on IS positions, as they did on Nov. 27, but to do much more than that would involve moving large numbers of forces over the Euphrates River. There are only two possible bridges from which to do this and IS is more than capable of blowing up a couple bridges.

To the east, IS has lost ground in recent weeks, since it retreated from Sinjar on Nov. 13. Sinjar sat on a highway connecting Syria and Iraq but it is not the only link between Islamic State lands so its loss was not crucial. Similarly, while al-Hasakah province is valuable land, it is not Islamic State’s core. The Syrian Democratic Forces, a coalition of at least 13 various Syrian rebel groups dominated by the Syrian Kurdish YPG, has recently pressed an offensive against IS from al-Hasakah city and on Dec. 1 managed to seize Hasakah dam, approximately 25 kilometers (16 miles) south of the city. This, however, should not be read necessarily as a defeat for IS. It is unclear how many SDF forces are involved in this offensive. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights among others estimate that the total number of SDF forces could be as many as 40,000 or 50,000, but how many are involved in this offensive is still unclear and IS seems to be retreating rather than being actively defeated in combat. This is because this territory is not of extreme significance in protecting the IS core. IS is rather pulling its forces back in a defensive posture, from which they will be difficult to dislodge.

The million-dollar question that no one seems to be able to answer is: How many fighters does the Islamic State have? The CIA has estimated between 21,000 and 30,000. This seems unreasonable at this point, as IS would not be able to hold as much territory as it does and sustain the level of operations it is with so few fighters. Kurdish sources talking to the Independent newspaper claim the number is actually 200,000. This also strikes us as beyond the pale, and indeed Kurdish sources would have an interest in inflating the numbers. Al-Jazeera has cited its own IS sources claiming the group has 50,000 Syrian fighters and 30,000 Iraqi fighters.

Whatever the case, it is clear that IS has enough fighters to maintain its core and to defend some of the key places its enemies will seek to attack in order to defeat the group. Furthermore, IS’ forces are divided among its various provinces. IS divides its territory in Syria and Iraq into 12 provinces in both countries. Each province has its own military force that is divided into different groups, such as special forces, air defense, snipers and administration. Furthermore, each province’s force is not supposed to move from province to province. Rather, there is an elite fighting force within IS called the Caliphate Army, which reports estimate is composed of about 4,000 or 5,000 fighters, and this group moves to various regions of conflict as needed. Reports in July suggested that this elite fighting force had pulled back to the Raqqa-Deir el-Zour core in order to shore up defenses there.

Assessing IS’ Position

The Islamic State finds itself in a relatively secure position despite its tactical retreats in October and November. Raqqa and Deir el-Zour are being attacked by U.S., French, Russian and now British airstrikes, but these airstrikes are not going to destroy the Islamic State by themselves. There is a limit to what can be accomplished with airstrikes and, unless one were to level all of Raqqa and Deir el-Zour, killing many civilians in the process, Islamic State will be able to withstand them. In addition, it is not obvious that the available aircraft could conduct a campaign of attrition if it were desired. The force is designed to attack specific targets provided by intelligence. It is a finite force dependent on the quality of intelligence available.

On the ground, meaningful threats to the Islamic State core are relatively limited. The first thing to keep in mind is that the Islamic State is located in the middle of the desert. No matter what direction one wishes to attack from, supplying large numbers of troops over a vast desert terrain would be required. This would be a very expensive prospect, even for a country like the United States, but especially for the limited militias currently fighting on the ground. In addition, IS has shown itself to be a very capable guerilla force when retreat, dispersal, regrouping and attack are called for. In many ways, its ability to absorb blows and counter at the time and place of their choosing is the most important characteristic of any military force and thus far IS has demonstrated this capability. IS would not necessarily have to defeat an enemy force head-on, but merely disrupt the supply line or counter attack at its opponent’s weakest point. Such maneuvers require unit cohesion and morale. Thus far, IS has shown it has sufficient amounts of both to absorb defeats.

To the southwest, the Islamic State’s hold on Palmyra is not being threatened. IS’ biggest challenger in this region would be Assad’s forces but the regime has more important priorities to the north in Hama and Aleppo. The regime would likely not push eastwards into the desert, as it would have to commit resources and manpower that it cannot afford with various rebel groups and the YPG continuing to attack regime-controlled territory.

Meanwhile, attacking from Hama, Aleppo or Tal Abyad also presents its own issues. The main problem for each of the three approaches is that they involve not cutting Islamic State off from a vital supply line and choking Raqqa into its demise, but rather a direct assault on Raqqa itself. It is possible that such an assault would be successful, but Islamic State has been ensconced in Raqqa since March 2013. It has had ample time to develop the city’s defenses. Furthermore, its fighters are a highly capable fighting force with high morale, one that has shown time and again that it is capable of retreating, suffering a defeat or high casualties, and continuing the fight with even more tenacity. Taking Raqqa from IS is possible if one is willing to sustain an extremely high casualty rate and it is unclear if any of the various rebel militias and groups on the ground have the appetite for that kind of battle.

Driving south from al-Hasakah and cutting off IS from Iraq, leaving Deir el-Zour and Raqqa to their own devices and significantly curtailing IS’ ability to move freely between the Syrian and Iraqi theaters is perhaps the most attractive line of attack. But here too the realities of ground warfare must be taken into account. It is all well and good that the Syrian Democratic Forces have as many as 40,000 troops in al-Hasakah, but it is another thing entirely to have enough trucks to get their troops from al-Hasakah to As Suwar, let alone far enough south into the desert to cut IS off from Iraq. IS is also used to operating in the desert and the rocky areas around Deir el-Zour give it a defensible position from which to either attack the supply lines of a large force moving south, or make an end-run around such a force and attack al-Hasakah or some other vulnerability created by a force of that size moving away from its base.

Implications

IS is by no means in an easy situation. It will continue to be the subject of air attacks from an increasingly long list of the world’s most powerful militaries and currently it has no real allies on the ground. Its leaders will have to continue to maintain the morale of its fighters in a battle that has turned towards a more defensive posture since its early victories in Palmyra and Mosul that inspired foreigners and locals alike to join the Islamic State’s ranks. IS has captured a great deal of weaponry and armor from the Iraqi army and other opponents it has defeated, but its ability to resupply or acquire new military hardware is dependent on smuggling and continued conquest. IS is also faced with the challenge of maintaining an economy, a topic which we will treat in depth in a future assessment.

The presence of such challenges, however, should not be used to confirm the notion that the Islamic State is simply going to collapse upon itself. The Islamic State is a state in a highly defensible position, with a clearly defined core territory and a sophisticated military that is deployed strategically. Wars are not won by airstrikes, nor are they won by press releases announcing the deaths of thousands of enemy combatants or the fall of hundreds of enemy villages and towns. The war against IS is a war against a coherent state and the coalition’s current strategy is a slow, deliberate military strategy that relies on the ability of disparate rebel forces, often with competing interests amongst themselves, to work together and continue to fight even when sustaining high casualties at the hands of a motivated enemy. Such a scenario is theoretically possible – but a great deal is possible in theory. The geographic reality is much less forgiving.