Originally produced on Oct. 16, 2017 for Mauldin Economics, LLC

By George Friedman and Allison Fedirka

As the fourth round of NAFTA negotiations comes to an end, the agreement’s survival has once again been brought into question. US President Donald Trump has threatened to strike a new deal with just Canada. Mexico downplayed the threat, saying it would walk away from negotiations if the new terms brought by the US put it at a disadvantage. For their part, the Canadians have been quiet, keeping their cards much closer to their chests.

All this commotion belies the fact that no NAFTA member is likely to walk away from the deal. The economic realities and commercial interests that led to its formation in the first place still incentivize cooperation, no matter how much any side postures.

An Apparent Advantage

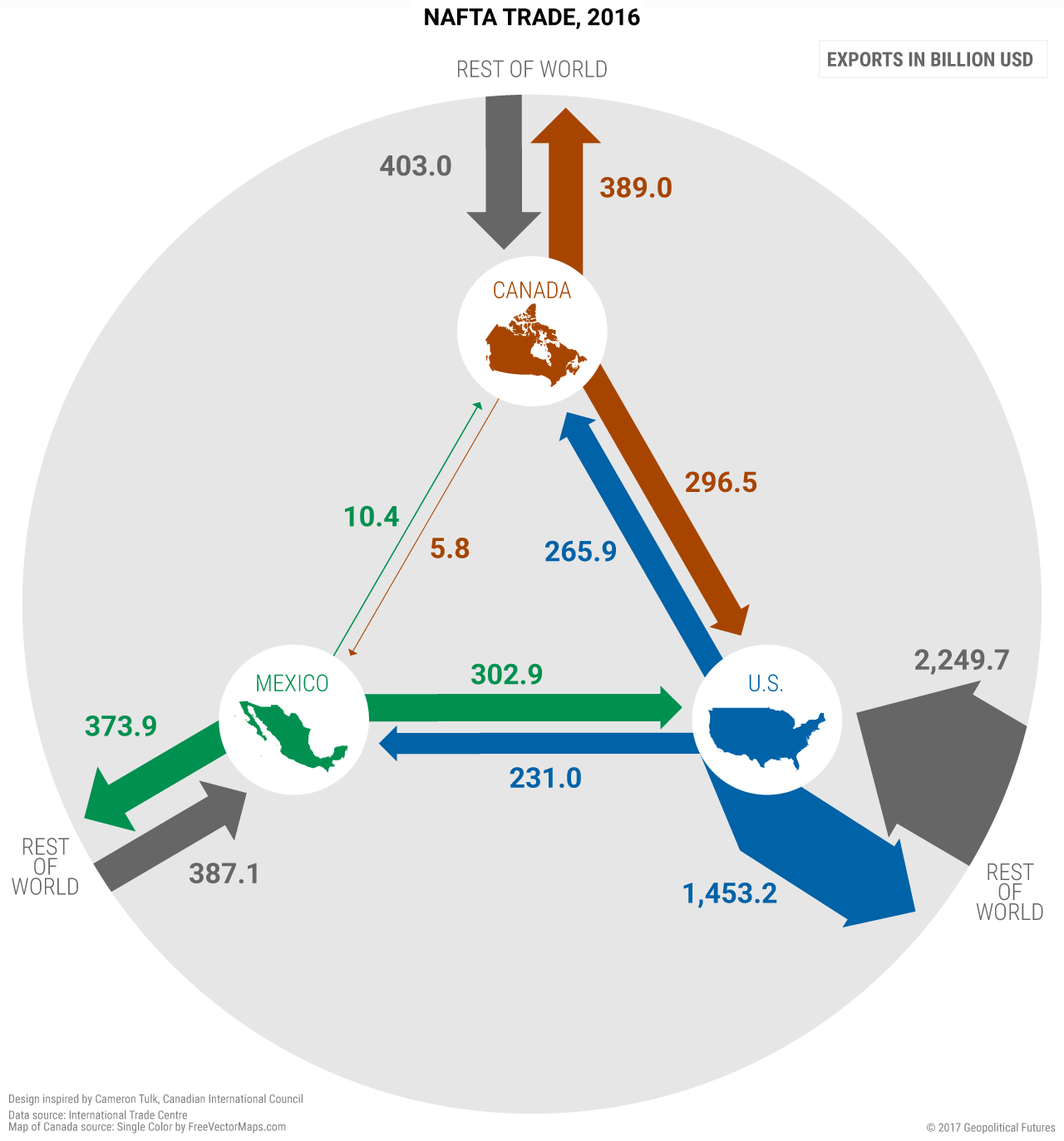

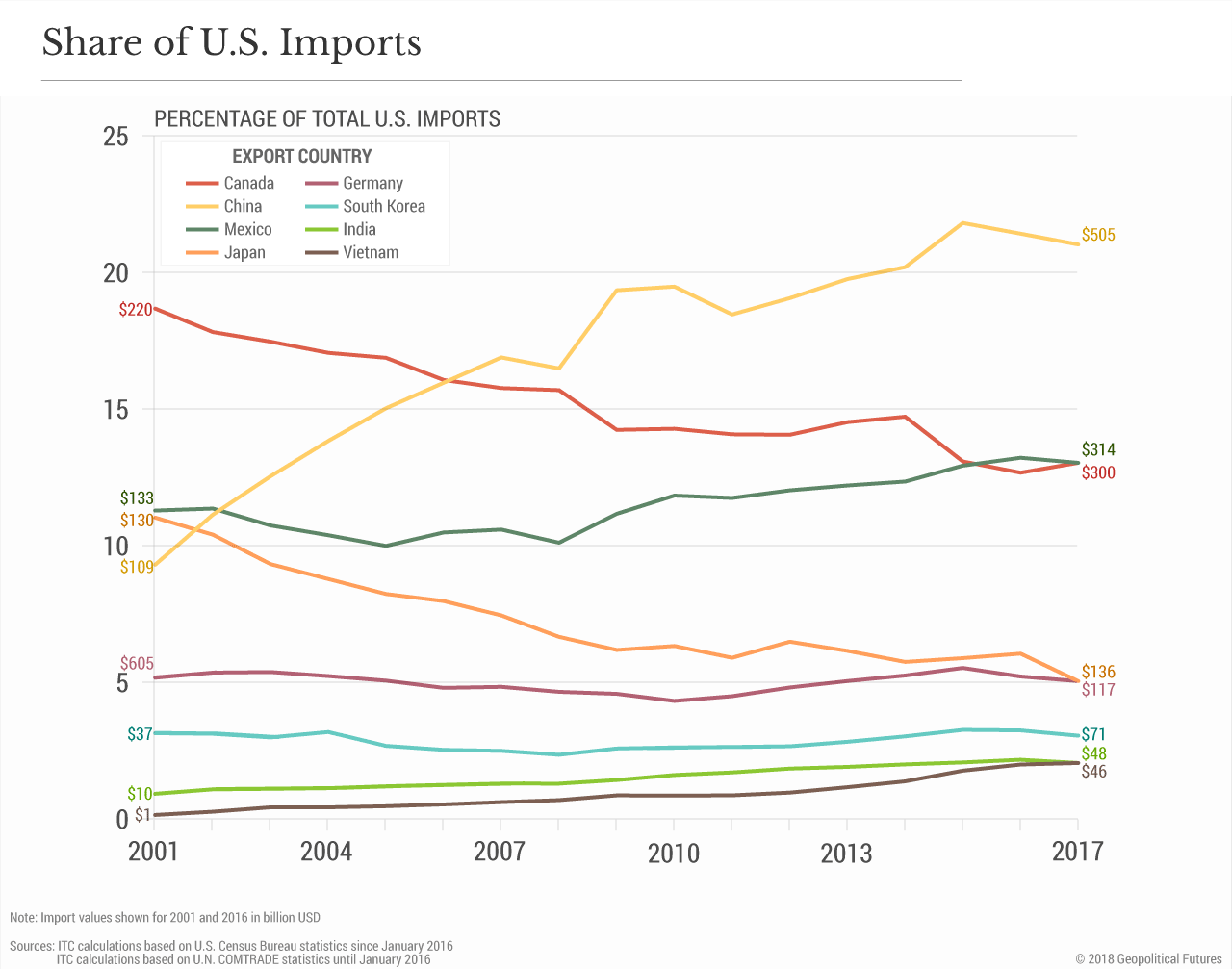

Still, at first the glance, the United States appears to have the upper hand. It boasts the largest economy in the world and accounts for about a quarter of global gross domestic product. Exports account for only roughly 12% of its GDP, according to the Department of Commerce, so the US has the benefit of a strong consumer class to boost economic activity when international demand is low. Easy access to such a large and vibrant consumer market has enabled Mexico and Canada to build up their economies without having to trade much with each other. In Mexico, on the other hand, exports account for about 38% of GDP, and about 81% of those go straight to the United States. Exports account for 31% of Canada’s GDP, according to the World Bank, about 76% of which go to the US. Exports are simply more important to the Canadian and Mexican economies than they are to the US’s.

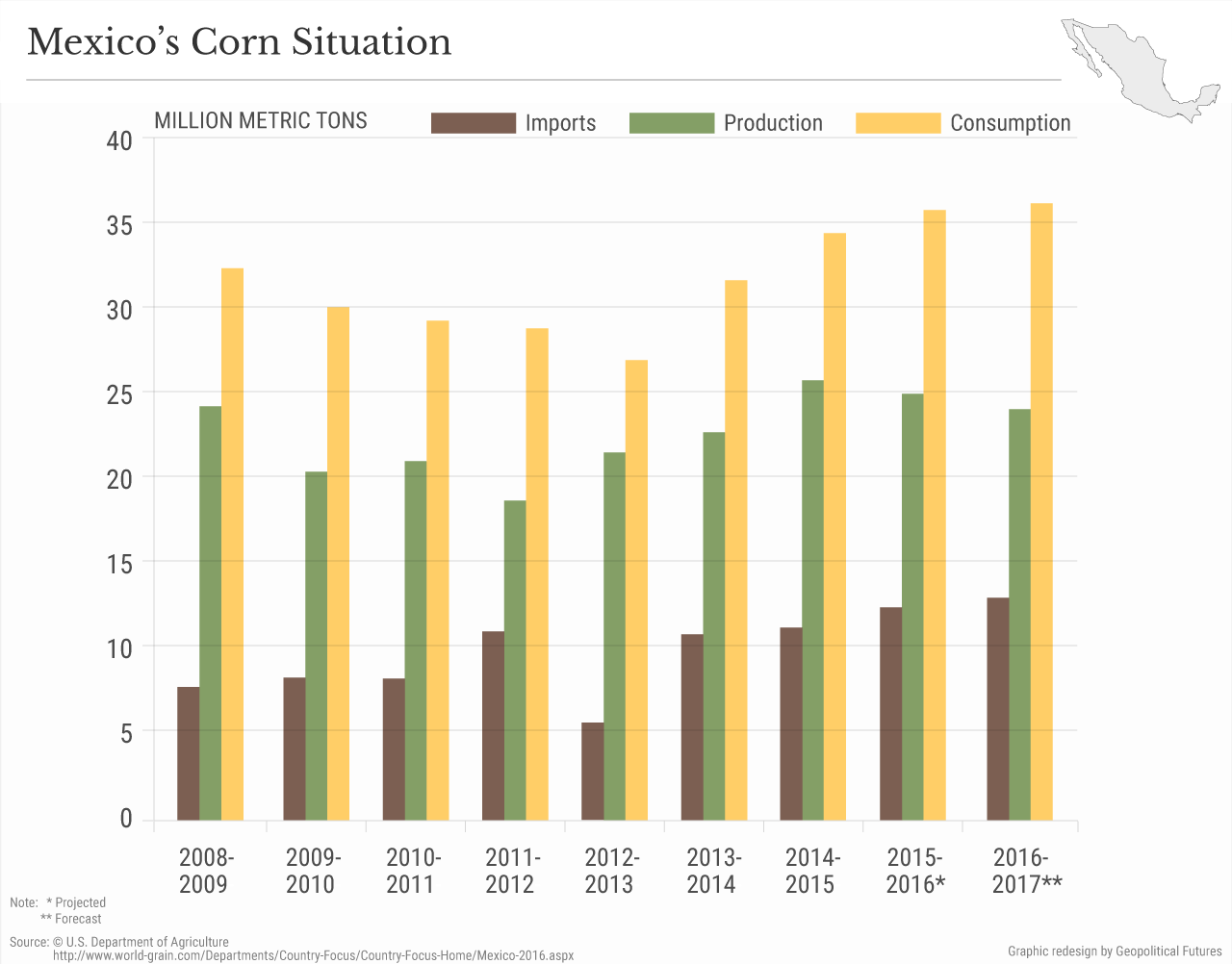

In keeping with this apparent advantage, there are a few areas in which the United States could hurt Mexico if Washington decided to restrict trade or impose tariffs. These include gasoline, steel, agriculture, and automobiles. Though Mexico produces crude oil, it relies on imports for most of its refined gasoline. Last year, according to Pemex, Mexico imported 62% of its gasoline, mostly from the US. Mexico is a net consumer of steel, importing about 40% of it from the US. (By comparison, the US sells just 4% of its steel to Mexico.) Mexico relies on the US for 85% of its total soybean supply and almost exclusively on the US for corn—a staple of the Mexican diet—accounting for a third of the country’s total supply. In automobile production, Mexico and the US have very integrated supply chains such that either one has the potential to disrupt the other.

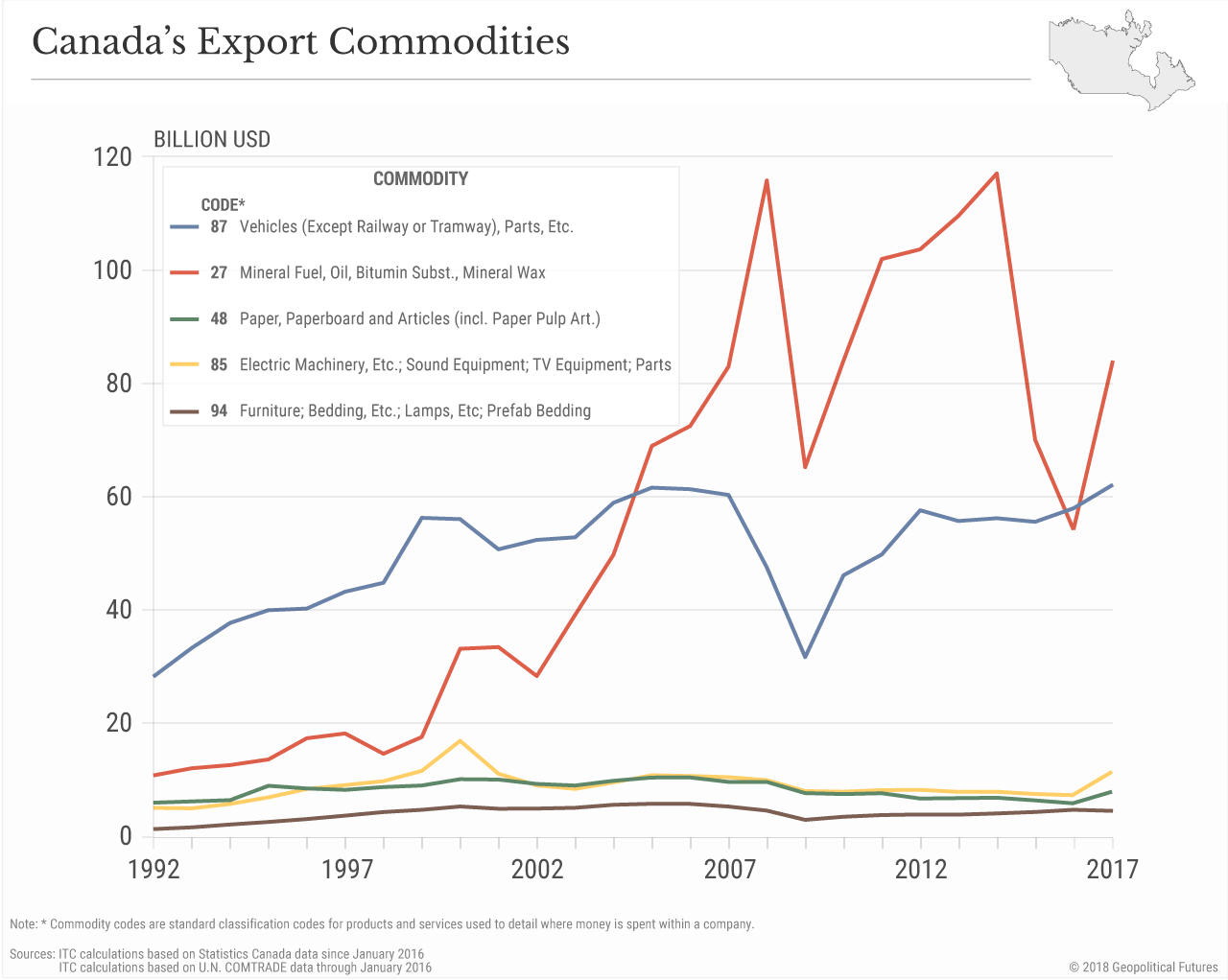

Canada’s major vulnerability is in oil. Oil is Canada’s most important export, and the US is practically Canada’s only customer. Meanwhile, some 40% of the oil the US imports comes from Canada, but that number is declining. Over the past 20 years or so, Canada has been developing oil production capabilities as manufacturing fell. For a few years, before the US shale revolution and the fall of oil prices, oil production was a boon to the Canadian economy. Since around 2014, however, the oil sectors in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador have declined dramatically.

A Closer Look

At a national level, the US dominates its northern and southern neighbors. But a closer look at state economies shows a different dynamic. California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, for example, rely heavily on trade with Mexico. They have a combined GDP of $4.5 trillion, or roughly a quarter of the country’s GDP, according to the US Bureau of Economic Analysis. Mexico, moreover, is among the top three export destinations for 33 of the 50 US states. Canada is the main destination of exports for 35 states and a vital source of oil to the US Midwest.

Similarly, the US business community has warned that major changes or dissolution of the trade agreement would be disruptive. Leading the charge is the US Chamber of Commerce, which has said that a US withdrawal from NAFTA would have catastrophic economic consequences for businesses. The American Farm Bureau Federation, meanwhile, acknowledges that despite competition of some products among the three nations, US farmers still rely heavily on trade for the sale of their goods. US agriculture exports to Mexico have nearly quintupled since NAFTA started, amounting to $17.9 billion last year. Even some members of the US automotive industry have urged caution in the renegotiations and that major changes are unnecessary.

NAFTA is going to be renegotiated, of course. Such agreements tend to be modernized to reflect new business practices, technological changes, different investment policies, and amendments to intellectual property law. But there would be severe political and economic consequences for walking away from the agreement. As talks address the more contentious topics, the rhetoric surrounding the negotiations will likewise become more vitriolic. But this is just one act in the theater of negotiations, and all sides are playing their part.