By Antonia Colibasanu

Several countries in the borderlands between Russia and the rest of Europe are changing leadership – but not their foreign policy. Russia-friendly politicians won presidential elections in Bulgaria and Moldova. On Nov. 9, the Estonian parliament passed a no-confidence vote against the government that may lead the pro-Russian Center Party to head a new coalition government. In Montenegro, the pro-Western Democratic Party of Socialists is still negotiating to form a governing coalition after winning the most votes in last October’s election but failing to secure a majority.

While elections are mostly about socio-economic policies, in the Eastern European borderlands, campaigning is also about geopolitics. The international media often focuses on the pro-Russian or pro-Western approaches these countries will take following elections. These campaigns often highlight the level of influence that particular external actors have within a country. Russia has maintained a high level of influence in Moldova and Bulgaria following the end of the Cold War. It has invested in maintaining good economic ties and influence in Montenegro and has worked to increase influence in the Baltics. The West has also worked to increase its influence in these borderlands. While these ties influence decision-makers, their foreign policies are more often dictated by national interests.

The borderland countries have always looked to balance the West against the East, making sure security risks remain low. The region has always faced the possibility of invasion. At the same time, these countries see Russia’s weakening as a sign that it could become more aggressive. As Moscow deals with economic problems caused by low oil prices and tries to contain any potential societal stress, the borderland countries are also in distress – for different reasons.

Estonian economic growth has been modest during the last few years, as it continues to recover from the 2008 financial crisis. Until 2014, Russia was one of Estonia’s largest export destinations, and the Baltic country was profoundly affected by EU sanctions imposed on Russia in 2014. Prime Minister Taavi Rõivas and his Reform Party have been in office since April 2015. But economic stagnation has led to conflicting views between the governing parties on taxation and other economic policies. This led the Social Democrats and the Res Publica Union to team up with the Center Party to oust the Rõivas government on Nov. 9. The Center Party is historically pro-Russian and represents the country’s Russian minority, about a quarter of the population.

Before the no-confidence vote last week, the Center Party’s openly pro-Russian leader Edgar Savisaar was replaced by the moderate Jüri Ratas. The Social Democrats have hinted he could become the next prime minister. This is a key change, because in 2010, Estonia’s intelligence agency, Kaitsepolitsei, labeled Savisaar an “agent of influence” for Russia and a “security threat” after he received 1.5 million euros (about $2 million) from a Russian nongovernmental organization. Estonian media report that political leaders have reassured the public that the political crisis is a domestic issue and will not lead to a change in foreign policy.

Ratas acknowledged that while a cooperation protocol signed in 2004 between Russian President Vladimir Putin’s United Russia Party and the Center Party still exists, it has been frozen for many years due to “very difficult and complex relations” with Russia. Ratas is an outspoken critic of Russian foreign policy and has already said that Estonia’s stance regarding NATO and the EU will not change. So, even if the Russian minority party forms a government, Estonia is unlikely to become pro-Russian.

In Bulgaria, former air force commander Rumen Radev and the Socialist Party won the elections. As a result, Prime Minister Boyko Borisov handed in his resignation, as promised if the governing party’s candidate didn’t win presidential elections. Radev won the elections on a wave of discontent with the ruling center-right party’s progress in combating corruption and disappointment with the EU. Initially presenting himself as an independent candidate, Radev has spoken out against the resettlement of refugees in Bulgaria. He also has argued that a more pragmatic balance between EU and NATO membership requirements is needed while the country seeks benefits from its relationship with Russia.

This is no different than Borisov’s approach. Borisov didn’t agree with Romania’s proposal to establish a permanent flotilla in the Black Sea, even if Bulgaria later agreed to participate in the multinational NATO brigade stationed in Romania. Borisov also restarted dialogue with Russia, discussing with Putin last August major energy projects in Bulgaria, including the Belene nuclear power plant and the South Stream natural gas pipeline. The two sides agreed “to step up interaction within the framework of the Russian-Bulgarian Intergovernmental Commission on Economic, Scientific and Technical Cooperation.”

Radev’s election will have no impact on Bulgaria’s stance on Russian sanctions as it will be up to the incoming prime minister to discuss them in Brussels in December. Radev will take office in about two months, after the current president’s term expires. The interim government will remain in place until spring 2017, when early elections will be held. Little to nothing will change in the short term.

In Moldova, while the president has limited powers in establishing the country’s policies, it is the first time in more than two decades that the president was elected by popular vote. A sense that the vote was the will of the people gives more legitimacy to the president. Pro-Russian candidate Igor Dodon won the election against pro-European candidate Maia Sandu. While campaign propaganda showed Dodon shaking hands with Putin, his electoral platform stated that he hopes to “restore relations with Russia while maintaining good relations with the EU.”

Dodon was deputy prime minister and economy minister in the last Communist administration led by former President Vladimir Voronin until 2009. Voronin announced in 2008 that Moldova would start negotiating an Association Agreement with the EU. The goal for Chișinău back then was to obtain a visa-free regime and enhanced free trade with the EU. As part of the team beginning to negotiate Moldova’s enhanced relations with the EU, Dodon understands the strategic advantages of a Moldovan agreement with the EU. Dodon’s claims of rapprochement with Russia refer to restarting exports to Russia, one of Moldova’s most important markets closed by EU sanctions. Even if early elections are called, which the Socialist Party likely would win, Moldova would continue to maintain balance between Russia and the West to gain economic advantages.

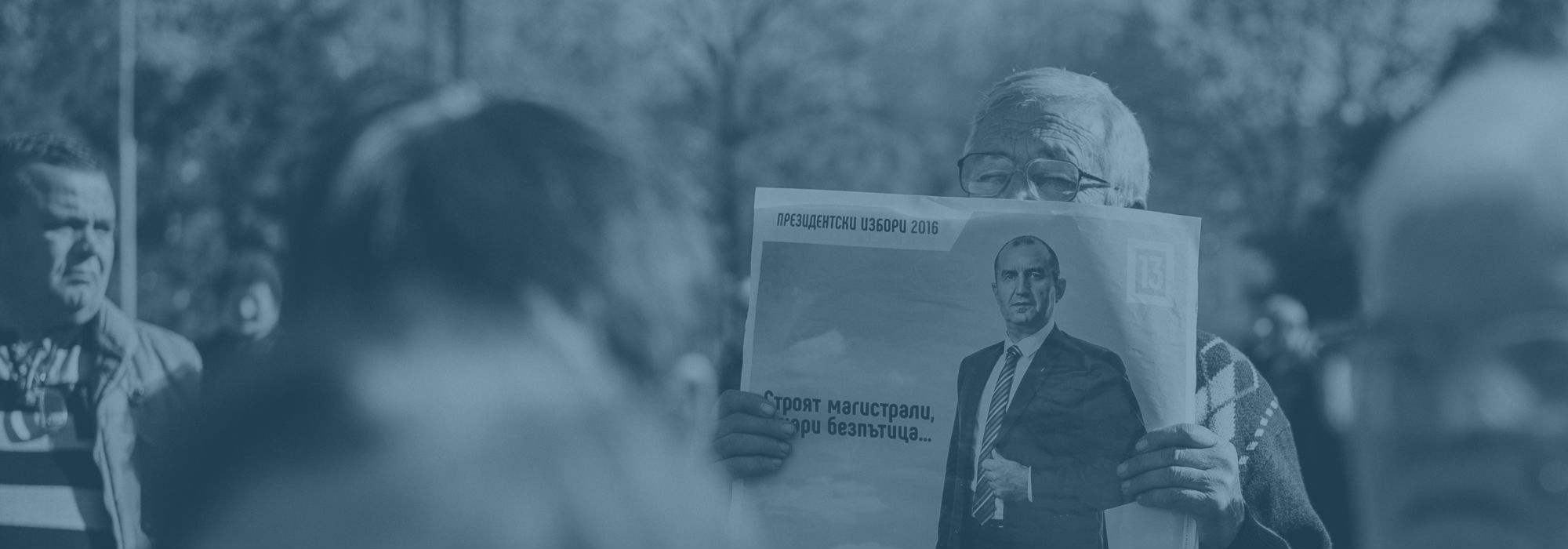

A supporter of the Bulgarian Socialist Party holds a picture of former air force commander Rumen Radev during a pre-election rally in the town of Byala Slatina, on Nov. 2, 2016. DIMITAR DILKOFF/AFP/Getty Images

Montenegro was invited to join NATO in December 2015 and is continuing accession negotiations with the EU. But Montenegro’s economic links to the West are limited as the country’s economy has grown mostly due to Russian investment in mining, energy and tourism. Russia does not support Montenegro’s accession to the EU or NATO. Montenegro’s independence stems from the country’s national imperative of aligning itself with the West. After the Balkan violence in the 1990s, Russia saw its regional power diminished as it faced internal problems following the collapse of the Soviet Union. As Western tutelage became the organizing principle for the region, Montenegro obtained its independence from Serbia in 2006 – despite the vast majority of the population being Serbian – in order to access NATO and EU expansion. The Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS) has been in government since 2006, and Prime Minister Milo Đukanović has consistently worked to advance EU and NATO accession.

The 2016 elections marked the first time the DPS leadership was challenged. The four pro-Russian opposition parties united over a single common goal of toppling Đukanović by campaigning against his tolerance for corruption. Reports of an alleged coup attempt thwarted on election day, Oct. 16, in which Montenegrin officials claimed Russia played a role, highlighted Russia’s opposition to the country joining NATO. Weapons found near the Serbian prime minister’s home also underscored Russian influence in the region. While Montenegro has maintained close economic relations with Russia, Serbia also has been under Russian political influence. But with Russia’s economic problems growing in the last few years, both Serbia and Montenegro hope to deepen ties with the West. This tendency will continue. A governing coalition the DPS is negotiating with the Social Democratic Party and four representatives of ethnic minorities will continue Montenegrin accession to both NATO and the EU, as they are core to the country’s strategic interest.

Elections matter little, even when campaigning is about geopolitics. Pro-Russian or pro-Western parties may govern, but they can’t shape a country’s geopolitical imperatives because they are embedded in its national interest. The current most stringent Russian imperative is to maintain internal stability. While working to reform its economy – a long, difficult process – Russia needs to act internationally. Russia is lobbying the EU for an end to the sanctions while working to maintain and expand its influence in neighboring countries. Russian concerns and moves are felt in the borderland more acutely than elsewhere. The platform for winning elections in these countries, while targeting socio-economic problems arising from the 2008 crisis, includes the divide between Russia and the West. As EU fragmentation increases and Brussels loses power, pro-Russian rhetoric gains ground. However, considering the strategic economic interest in remaining close to the West, borderland countries will not shift their foreign policy to fully embrace Russia.

To learn more about the future of Russia, read our free special report Putin and Russia’s Illusion of Power.