By Jacob L. Shapiro

China just wrapped up its first ever counterterror military exercises with Saudi Arabia yesterday and also concluded its first ever counterterror military exercises with Tajikistan on the Tajik-Afghan border earlier this week. On Oct. 20, China hosted mercurial Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, promising increased cooperation between Beijing and Manila, while giving Duterte another chance to loudly criticize the United States. On Oct. 19, the mere fear of Chinese anger at the Dalai Lama visiting the Czech Republic prompted a statement from the Czech president affirming China’s “territorial integrity.” On Oct. 9, China’s vice foreign minister said in a briefing that Russia and China held similar positions on the current situations in both Syria and Iraq and were working closely together in both arenas. And the month began with the yuan being officially welcomed into the International Monetary Fund’s basket of reserve currencies, called Special Drawing Rights (SDR).

Chinese workers pose at the inauguration site of a train linking Addis Ababa to Djibouti, 20 kilometers (12 miles) from the center of Addis Ababa on Oct. 5, 2016. The 750-kilometer-long railway, built by two Chinese companies, will link Addis Ababa to the Red Sea port city of Djibouti in about 10 hours, a far cry from the current excruciating multi-day trip along a congested, pot-holed road. ZACHARIAS ABUBEKER/AFP/Getty Images

October has not been an anomaly. The once non-interventionist government in Beijing behaves like a major player on the world stage today. China threw its hat into the Syria ring, promising training and humanitarian aid for President Bashar al-Assad’s regime on Aug. 18, four days after a Chinese rear admiral visited Damascus. In the same month, China hosted the first meeting of senior military officials from China, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Tajikistan to combat terrorism and extremism in Asia. In March, China declared it would build a naval facility in Djibouti and would station “a few thousand” troops there – China’s first permanent overseas operation. In January, China earned a seat at the table in the Afghan peace process with the U.S., Pakistan and Afghanistan after hosting Taliban leaders for talks in 2015. Last year, China provided one-fifth of all soldiers committed to the U.N.’s peacekeeping standby force. It also pledged $100 million to the African Union standby force and $1 billion to the U.N. Peace and Development Trust Fund.

These are all examples of a Chinese foreign policy that extends beyond China’s immediate interests. China’s foreign policy has historically been defined by local and regional imperatives. Squabbles in both the South and East China seas have been a source of great publicity and little practical import this year. The ebb and flow of tensions between China and its Japanese and South Korean neighbors make constant headlines. Every North Korean missile test or high-level Sino-North Korean meeting reminds the world that China is the country with the most diplomatic leverage in Pyongyang. But the laundry list of Chinese activities above goes beyond the issues China faces in its own backyard. At face value, it seems indicative of a China that is strong and getting stronger and willing to assert its own interests at the global level, even if those interests conflict with those of the United States.

The moves China is making are impressive, and I do not dismiss them. But they should not be seen as China attempting to increase its power at the expense of other global powers. China, despite its massive economy and its rapidly improving military forces, has internal weaknesses that preclude it from broadly increasing its power internationally. This weakness is rooted in China’s serious internal economic issues that threaten social stability and the rule of the Chinese Communist Party. For decades, the promise of prosperity was a fundamental part of the glue that kept the Chinese state together. China is now entering a new economic situation, in which the Communist Party cannot make good on promises of extremely high levels of growth and rapid enrichment of wide swaths of the population. In response, President Xi Jinping and the Communist Party have turned to Chinese nationalism as an alternative adhesive as they attempt a major transformation of the Chinese economy.

One overlooked part of this strategy is that it requires China to boost its global prestige. Take Syria as an example. China has no strategic interests in Syria. But the grisly images of the Syrian civil war dominate world headlines, and China can now say that it is playing an integral part. It is the same with many of the other issues Beijing has involved itself in this year. In the same way that China uses North Korea to its diplomatic advantage, China has gotten closer to Pakistan, which has put it at the negotiating table with the United States over the continuing war in Afghanistan. In Central Asia and Saudi Arabia, China appears like a paternalistic big brother, passing on needed skills and information in military exercises that will not stop terrorism. Inclusion in the IMF’s SDR means the yuan can be spoken of in the same sentence as the dollar, the pound, the yen or the euro. The fact that inclusion in the SDR will have little practical import doesn’t matter. The average Chinese citizen can look at such developments and feel pride in his or her country’s position in the world and in the Communist Party’s stewardship.

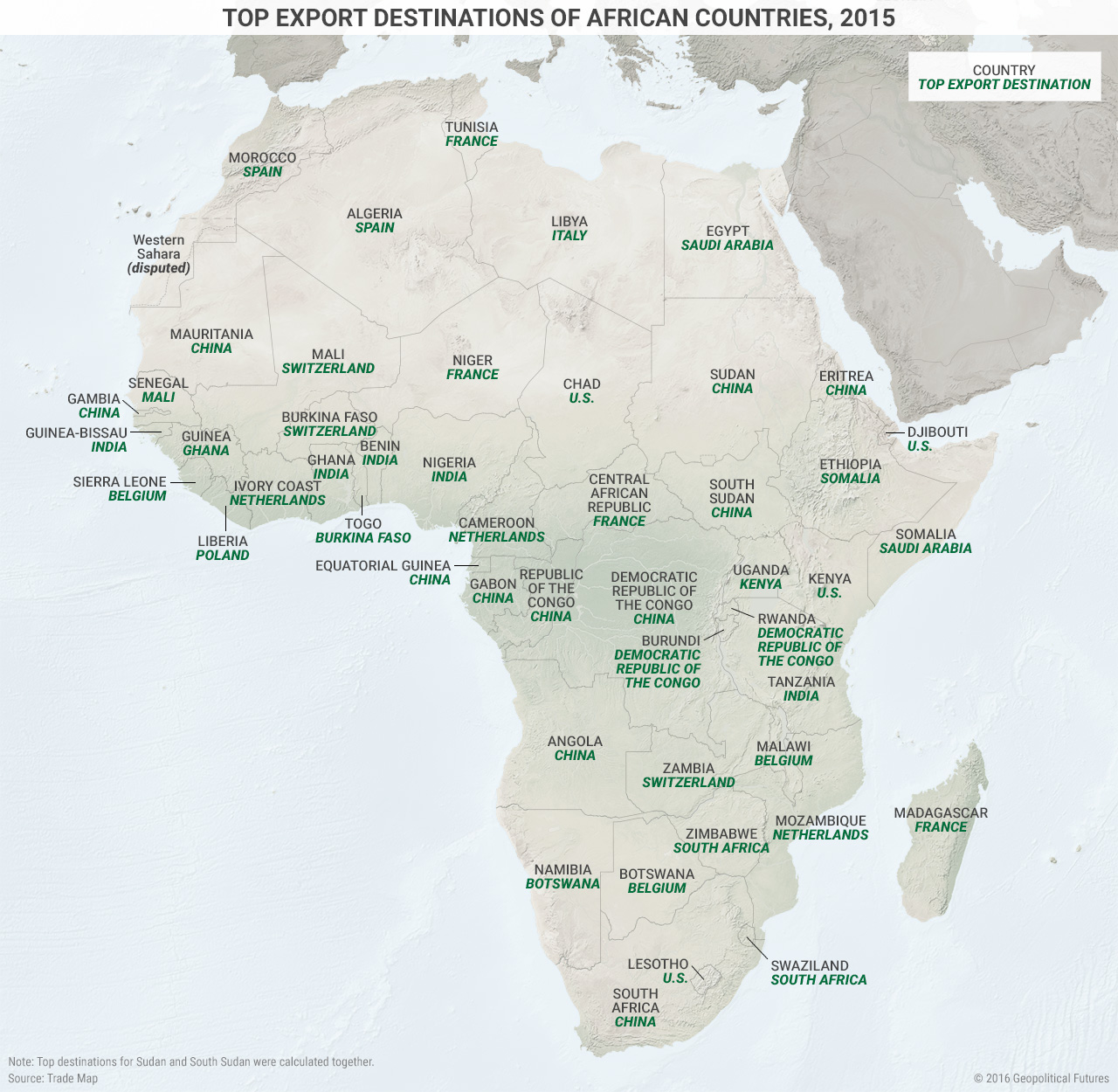

One of the most discussed storylines when it comes to China’s increasing power and influence in the world is its activities and investment in Africa. Taking apart this myth helps show the way this kind of prestige works. China is Africa’s largest trade partner, and according to Trade Map, roughly 12 percent of all exports out of Africa go to China. Speaking at the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation last December, Xi said China had pledged $60 billion in aid to African states. The U.N. has published extensive reports on the “breathtaking pace” at which relations and trade are growing between China and Africa.

China is active in Africa for strategic reasons, namely, access to the cheap raw materials that fuel its economy. But the inflation of China’s power in Africa is an excellent example of the way China is trying to use prestige to establish its international credentials. That $60 billion figure Xi threw around? The Washington Post reported that only $5 billion of that is grants, with the rest coming as loans and export credits. A 2015 Brookings report pointed out that for all of China’s investment in Africa, countries like France, the U.K. and the U.S. invest more in Africa than China does. The map above illustrates the limits of Chinese influence in Africa. Certainly, some countries depend on China when it comes to trade – but the majority are not. China is not even in the top 10 export destinations for Djibouti, where it is building its new permanent naval facility.

China is relatively limited in what it can do to increase its power. It also does not have a very compelling reason to try. The global shipping lanes on which its economy depends are open and protected by the United States. It has secure relationships with the various oil-producing and commodity-rich nations from which it imports raw materials. No one is attempting to invade the Chinese mainland – the biggest external threat to China right now is foreign ships coming within 12 miles of meaningless manmade islands in the South China Sea. Compared to most of Chinese history, the external threats China faces today are insignificant.

China is building up its prestige because it cannot afford to be embarrassed, and if it succeeds in creating a narrative about how powerful it is, it can stop challenges before they materialize. Furthermore, if China can demonstrate that it possesses a certain measure of power already, then the Chinese people will be willing to struggle with the economic hardship that has already started to become apparent, and other world powers will not step on China’s toes for fear of what China might do in retaliation. The key to understanding China’s recent international forays is to remember that China is not aggressively seeking to increase its power. It is aggressively seeking to demonstrate, both to itself and the rest of the world, that it already is powerful.