By Allison Fedirka

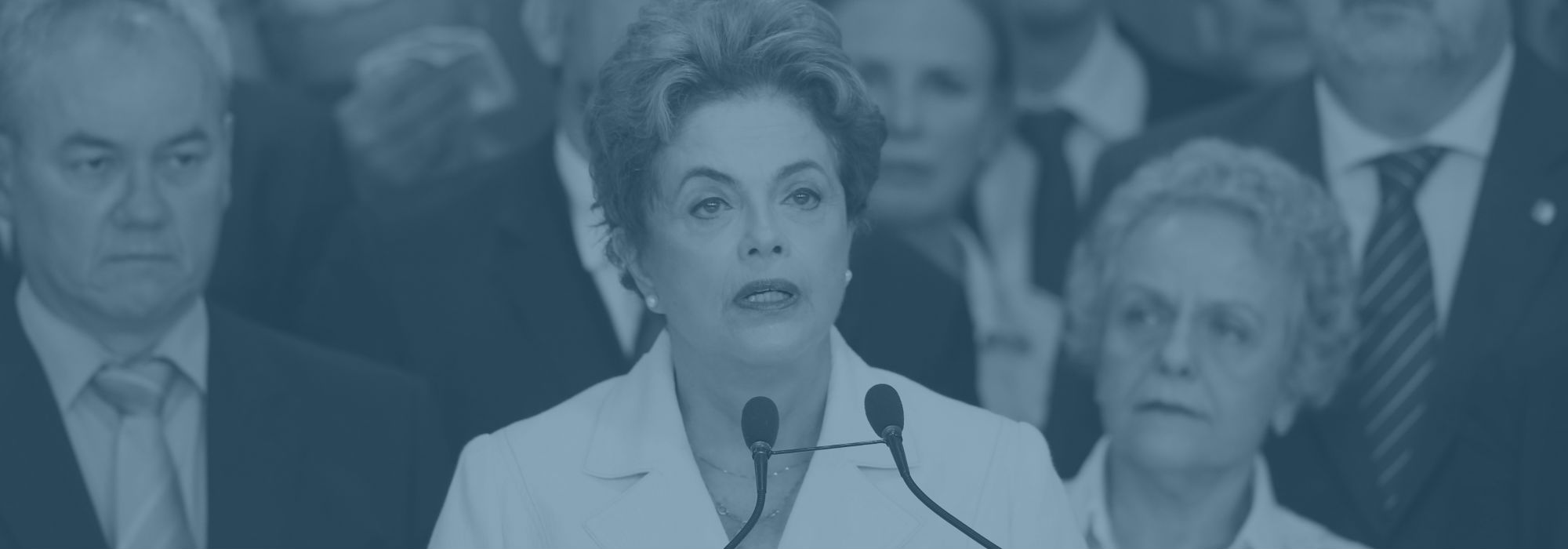

Yesterday morning, the Brazilian Senate decided to move forward with an impeachment trial against President Dilma Rousseff, resulting in her suspension from office. Expectations are high that she will be found guilty, impeached and her exit from office will mark the first step towards a slow recovery in the country’s economic and political crisis. Like most things, this is more easily said than done. There are two fundamental problems related to Brazil’s political and economic crisis today and neither one can be solved by a mere impeachment.

Politically speaking, there is a crisis of confidence among the Brazilian people toward elected government officials. Not unlike other countries, the general public view in Brazil is that the vast majority of politicians holding office are corrupt and cannot be trusted to govern. To be fair, this perception is not entirely misplaced. In a wave of corruption scandals, some of the country’s most powerful and highest-profile politicians, independent of party affiliation, have been suspected or found guilty of corruption or have been under investigation. These include Rousseff, Vice President Michel Temer, former Speaker of the House Eduardo Cunha and former presidential candidate Senator Aécio Neves. At the end of April, a Datafolha survey revealed that 61 percent of the population wanted Rousseff removed from office and 58 percent would support the impeachment of Temer should he take office.

However, there is a select, small number of public officials whose images have improved as a result of corruption scandals – judges and federal police officers. Those championing fights against corruption and not backing down from investigating powerful, corrupt politicians have gained favor among Brazilians. This is true in particular for Judge Joaquim Barbosa and Judge Sérgio Moro. Barbosa handled the infamous Mensalão corruption scandal that encircled former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Moro has led the Lava Jato (aka Petrobras) case that has so far incriminated dozens of CEOs and politicians in office. At the peak of the Petrobras scandal, social media estimates gave Moro a 90 percent public approval rating. Additionally, local media have, on more than one occasion, pitched these judges as potential presidential candidates in 2018. Neither judge has expressed interest in running for office at this time, but even the mention of such an idea reflects how strongly public opinion lies in their favor.

On the economic front, the introduction of Temer as president provides no guarantee that he will address the underlying challenge to Brazil’s national economic policy. His plans for government austerity do little to correct the structural disparities present in the Brazilian economy.

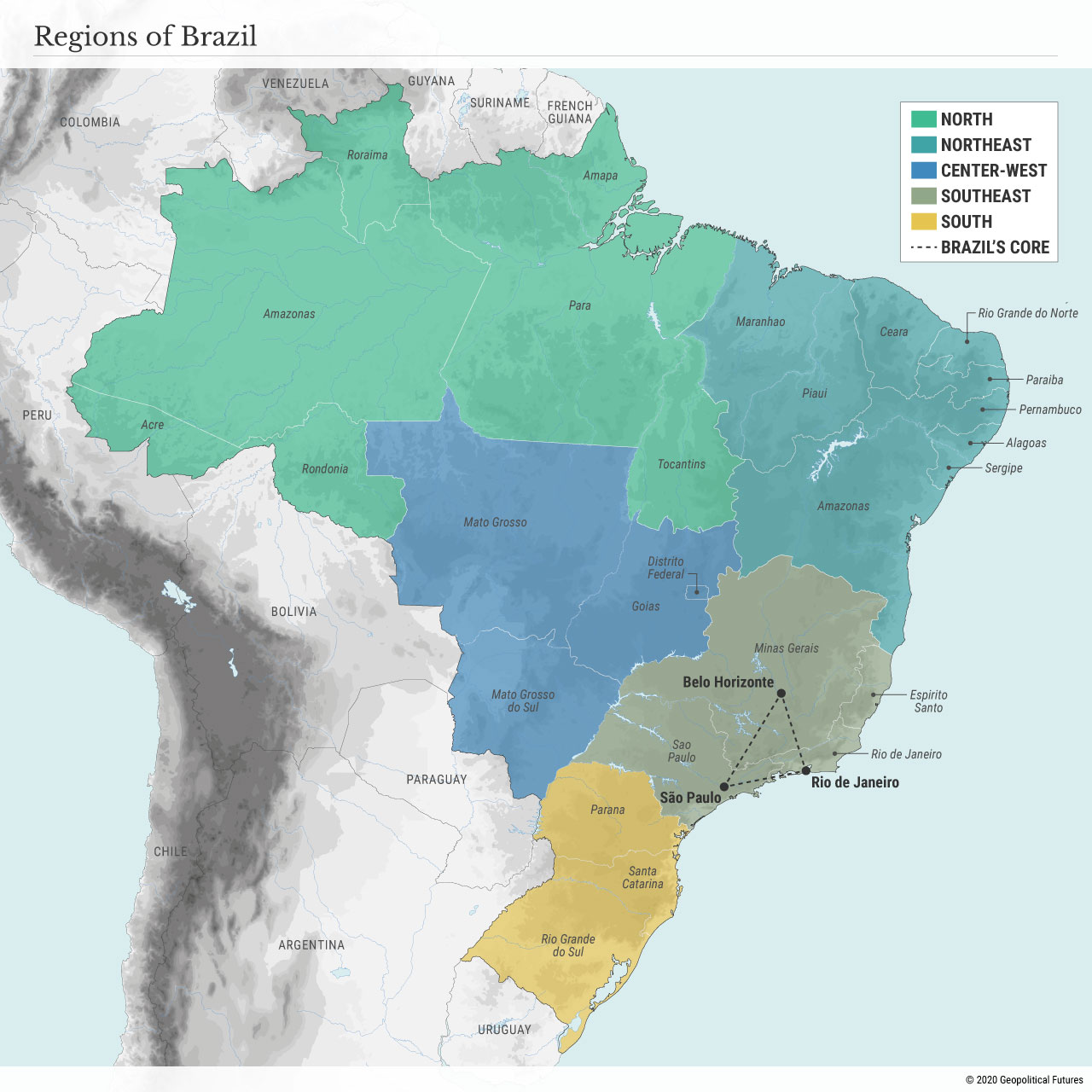

Days after Rousseff won her second term as Brazil’s president, late night talk show host Danilo Gentili used his opening monologue to satirically address political divisions in Brazil. He jokingly promoted the post-election notion that Brazil should be separated into two countries to reflect the division of the popular vote. Electoral results from Brazil’s 2010 and 2014 elections show a rather clear separation of red states supporting Rousseff in the north and blue states supporting the conservative/right candidate in the south. Joke all he wants, Gentili was right on the mark with the idea that there are indeed two Brazils. This duality is precisely what makes running the country – and especially the economy – so challenging.

The northern and southern states in Brazil have competing economic interests. When we say Brazil’s south, we are referring to the country’s South, Southeast and Center-West regions. This half of the country has a far more developed economy than the north with high value-added industrial and manufacturing activities like automobiles and airplanes. It is also home to the country’s major offshore oil deposits, large beef industry and soy-producing farmland. The south also hosts the most developed infrastructure networks and facilities in the country. The north of Brazil – composed of the Northeast and North regions – have economies that rely heavily on tourism, non-cash-crop agriculture, lower-level industrial activity and some mining. Infrastructure development in the north lags notably behind the south with limited and costly transportation routes.

The distinction between the economic activities in the north and south have also contributed to wealth disparity between the two halves of the country. The three states of Brazil’s Southeast region – São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais – account for 55.3 percent of the country’s GDP. Add on the Center-West and South regions and you have 80.9 percent of Brazil’s economic activity. The remaining GDP is spread out across the 16 states (of 27 total) that comprise the northern half of the country. Per capita income in the south ranges from 25,600 reais ($7,350) to 29,700 reais per month, while in the north monthly per capita income drops down to 11,000 reais to 14,200 reais. This distribution of wealth and economic activity helps explain why the northern states regularly support political parties, like Rousseff’s Workers’ Party, that favor social spending and government assistance programs. Meanwhile, the richer pro-business south tends to support conservative parties that promote market-friendly policies.

The decision to open an impeachment trial against Rousseff is geopolitically insignificant in and of itself. At Geopolitical Futures, personalities rarely matter. However, the impeachment proceedings do bring the political crisis of confidence and economic inequality facing Brazil to the forefront. These two items do have geopolitical significance in terms of the country’s potential for assuming regional leadership. Brazil must physically and economically connect and integrate its regions and then consciously decide to assert itself prior to assuming a strong, leadership role in the region.

While this has been achieved in the south, there are still clear economic divides in the county’s north. While these conditions persist, sustained regional leadership is not viable. An impeachment alone will not immediately restore confidence in elected officials nor resolve the economic disparities between the north and south. Additionally, these proceedings have illustrated a renewed sense of social consciousness and a level of institutional strength in Brazil; the military never intervened, court decisions were respected, constitutional processes were followed, etc. Both of these characteristics help provide a firm foundation from which Brazil can continue working toward its geopolitical imperative of incorporating the north with the south.