By Antonia Colibasanu

This week began with the release of numerous positive monthly statistics for the German economy. The Munich-based Ifo Institute’s latest German business climate index noted that business managers’ optimism has risen, considering that the index value for October is not only higher than last month but at its highest level in more than two years. At the same time, the Purchasing Managers’ Index, compiled by IHS Markit and used by the European Central Bank to assess the health of the region’s economy, indicated an accelerated increase in German business activity in October compared to September.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel speaks at the Christian Democratic Union Economics Conference of the Economic Council on June 09, 2015 in Berlin, Germany. The Economic Council (Wirtschaftsrat der CDU e.V.) is a German business association representing the interests of more than 11,000 small- and medium-sized firms, as well as larger multinational companies. Axel Schmidt/Getty Images

In addition, the Cologne Institute for Economic Research forecast that German exports to the U.K. will fall by just 6 percent next year due to the devaluation of the pound in relation to the euro following Brexit and that this decline will only marginally affect Germany’s economic performance in 2017. Lastly, the German development bank KfW released its latest report on the German middle class and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) on Oct. 25. It noted not only that the middle class is in “excellent shape” but that SMEs are continuing their strong performance, with stable sales growth of 3.3 percent and an equity ratio of 30 percent. All these developments seem to indicate that Germany has again become the driving force of the European economy.

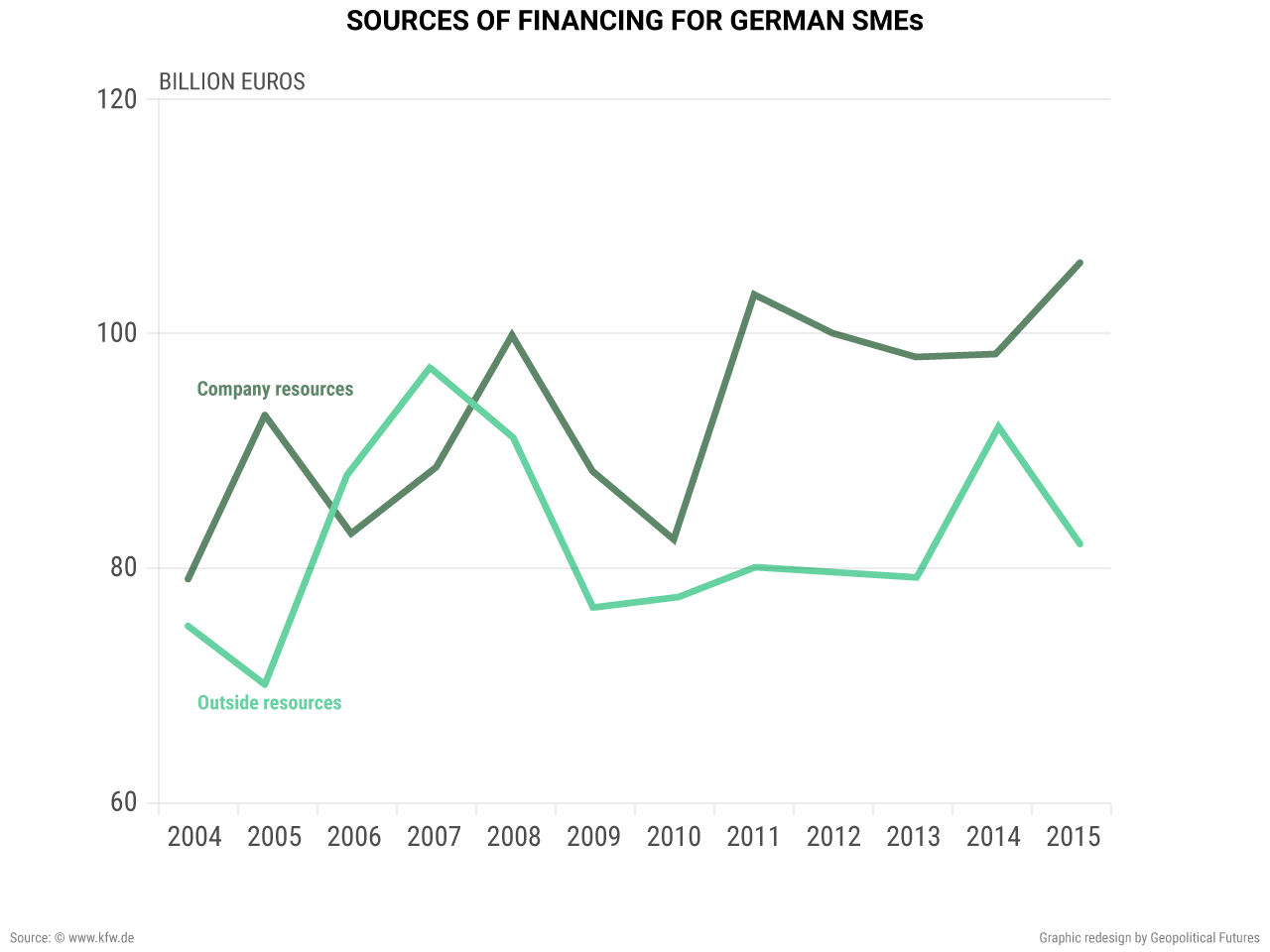

But, according to German central bank data, German companies’ appetite for investment is not picking up. German businesses outside of the financial sector have saved more than they have invested for the past seven years, which totals about 455 billion euros ($500.4 billion) in cash and deposits. The KfW report also points to the fact that most companies prefer to invest in the spot market and SMEs’ demand for loans to finance their investments has continued to decline since 2008, even though the interest rate has fallen. Most companies are turning to their own financial resources that they have built up over the years, rather than seeking external funding. In 2015, capital expenditures financed by the SMEs’ own funds totaled 105 billion euros, and the share of equity in investment financing was at 53 percent, an increase of 4 percentage points over the previous year.

While this may indicate that these companies are stable in the short term, it also indicates that they are worried about seeking external financing. Most German executives blame this trend on the weak prospects for economic growth as well as the fact that the tightening rules for lending after the 2008 financial crisis have forced the banks to become stricter when awarding loans, limiting SMEs’ access to credit. Reports in local German media earlier this month said that harsher rules imposed on the European banking system by the new EU regulatory framework have negatively affected banks’ profitability rates. At the same time, German industry associations have also pointed out that restrictive access to credit is having an impact on their members’ businesses. All this undermines the idea that optimism over the German economy is growing.

SMEs are the backbone of the German economy, making up 99.95 percent of all German companies and employing about 70 percent of the total workforce. Micro-enterprises with fewer than 10 employees account for about a third of SMEs’ workforce. Therefore, news relating to their willingness to invest is an indicator not only of the level of business optimism in Germany but also social stability. Most foreign sales for SMEs are in Europe, a market that is still contracting due to the Continent’s socio-economic problems. However, SMEs’ foreign sales outside Europe have continued to decrease – from 17 percent of total sales in 2013 to 13 percent in 2015. While sales in Germany have been boosted by domestic private consumption and residential construction, both of which have grown due to declining interest rates, the fact that small businesses are selling bonds to individuals and spending their savings reveals that they do not have much confidence in Germany’s economic future.

Complaints about banking regulations are normal, but it isn’t the bureaucracy that stops companies from investing – even if, indeed, there is more bureaucracy in the banking sector following the 2008 financial crisis. SMEs prefer to finance their spending by using their own resources because they are not sure future profits can pay back new loans. Businesses used to accept some risk by taking out loans to finance their projects. But this is becoming less common because the success of new projects is increasingly uncertain, especially in light of stagnant and even decreasing economic growth in Europe.

Instead, as rules for getting a loan have toughened, business managers’ trust in financial markets has declined. Risk aversion has risen due to managers’ worries about new crises affecting their businesses. They believe the benefits of taking out a loan today will be outstripped by the cost of paying it back in the future, especially if the economic outlook for Europe continues to be underwhelming. Such an attitude may work in the short term. While some positive indicators from the German economy relate to seasonality, considering that it is normal for consumption and industrial purchases to increase before the holiday season, investment relates to medium- to long-term prospects. German companies may rely on their own financial resources until better investment prospects become more apparent, but they may be waiting a long time. Until then, Europe’s political instability will continue to translate into cautious German investment behavior. This in turn lowers the ceiling for potential growth, which causes even more political instability on the Continent. And then, the cycle repeats.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East