When elephants fight, it’s the grass that suffers. Few understand this better than Latin America, which has been drawn into disputes between great powers in North America and Eurasia before, and might again. The focal point of the latest standoff between the U.S. and Russia is Ukraine, in Russia’s own front yard, but Moscow sees an opportunity to level the playing field by supporting destabilizing forces in Latin America. Russian diplomats in recent weeks have talked up the possibility of deploying weapons in the region, but the likelier danger is that violence along the Colombian-Venezuelan border could escalate and draw in Moscow and Washington.

Shades of the Cold War

Russia and Venezuela have for years found kinship in their mutual disdain for the United States. Recently, however, there has been a clear shift, particularly from Russia, from a loose friendship to a closer alliance with bellicose undertones. It started when Russia’s deputy foreign minister, Sergei Ryabkov, proposed deploying military infrastructure to Venezuela and Cuba. Two weeks later, Russia’s ambassador to Venezuela again raised the issue of Russian-Venezuelan military cooperation. Venezuela’s constitution prohibits the hosting of foreign bases, the ambassador noted, but it doesn’t rule out collaboration at ports. (He also compared the Venezuelan government’s 2019 political crisis to the sorts of color revolutions witnessed in Russia’s near-abroad, while Venezuela’s defense minister complained – without evidence – that NATO is gaining ground in Latin America and using Colombia – which is only an observer in the alliance and thus does not influence discussions or operations – as a pawn.) The Kremlin has also made it a point to draw attention to high-level talks between the two countries, including a call last week between Russian President Vladimir Putin and his Venezuelan counterpart, Nicolas Maduro.

This shift has not gone unnoticed in the U.S. and Colombia. Though neither has advocated a joint response to Russia’s moves, both have made clear that they reject the Kremlin’s influence in Venezuela’s affairs. Colombia, which closed its border with Venezuela over Caracas’ alleged support for Colombian guerrillas in the border area, said it would not be blackmailed by Russia into reopening the border. For its part, the U.S. said it would respond decisively if Russia deployed military hardware to the area, as Ryabkov suggested. It also warned in December about foreign interference in Colombia’s 2022 presidential election – a favorite Russian tactic. But otherwise, Washington’s response has been subdued. Immediately after Ryabkov’s remarks, the U.S. Air Force flew a reconnaissance aircraft over the Caribbean, but Washington did not widely publicize the move. Similarly, Washington has preferred not to put too much emphasis on Russian activities and collusion with the Venezuelan government and guerrilla groups, instead letting unofficial figures do most of the talking.

It’s all very reminiscent of the Cold War. Ryabkov’s remarks in particular called up memories of the Cuban Missile Crisis. But the idea of Russia moving significant military assets to Venezuela is impractical and should be considered a reminder of American vulnerabilities rather than a specific threat. This kind of deployment would require substantial funding and logistical capabilities that are already tied up in Russia’s near-abroad. Further, Venezuela’s general volatility discourages Russia (or anyone else) from placing major valuable assets there.

But Moscow doesn’t need to deploy major military assets to draw Washington’s attention to dangers closer to home. During the Cold War, the Cuban Missile Crisis was the exception. Most of the Soviet Union’s moves in Latin America involved supporting radical left-wing political and guerrilla movements – the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, the Tupamaros in Uruguay, and the original Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) – that threatened U.S. interests in the region. The strategy was extremely effective, even leading the U.S. on several occasions to sponsor coups in the region to bring pro-American governments to power.

Russia is more likely to repeat this strategy of supporting guerrillas and criminals in Latin America than it is to deploy major military assets. Both would divert U.S. attention and resources and give Russia leverage in negotiations, but the former involves far lower costs and risk.

Simmering Conflict

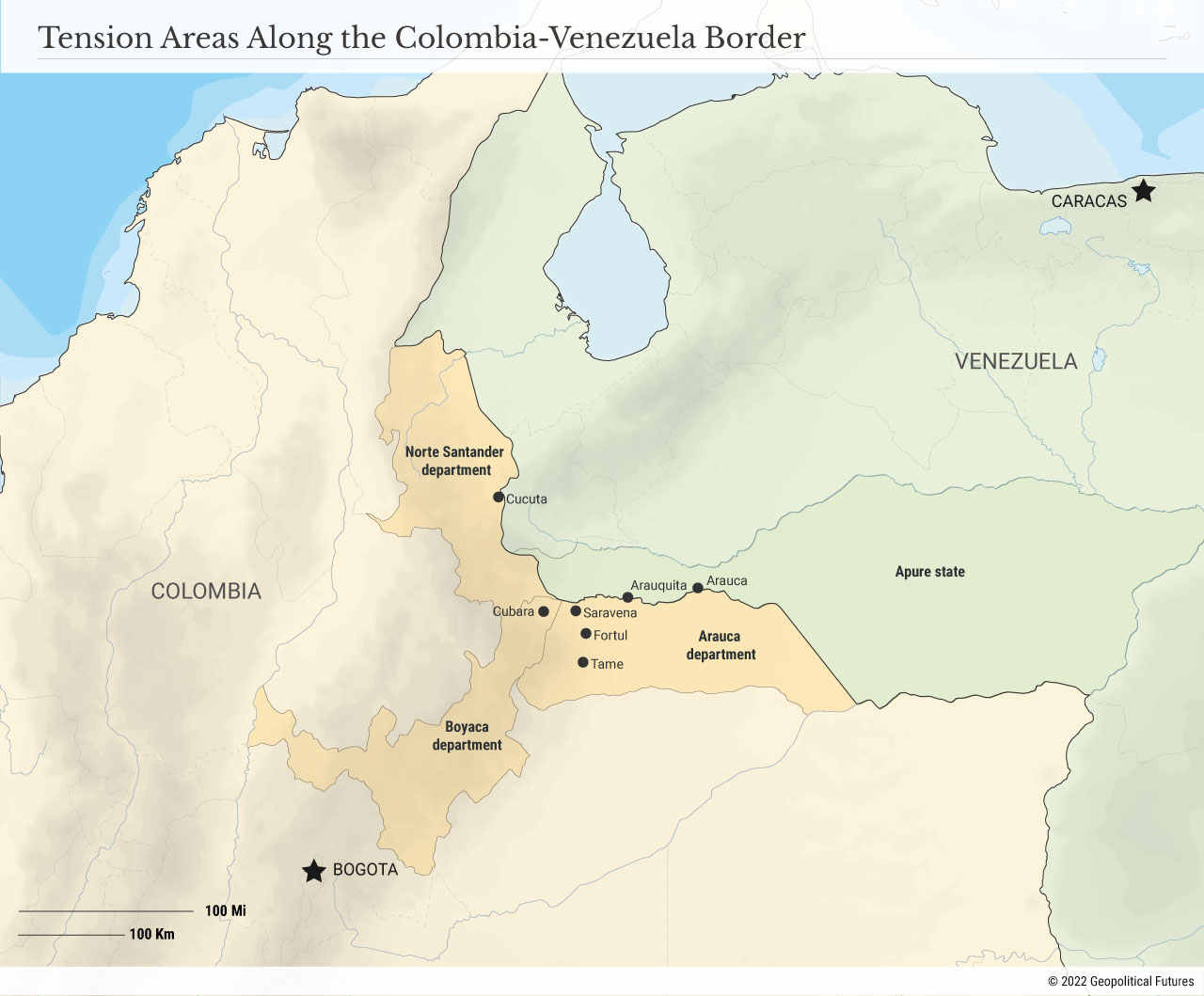

With that in mind, recent clashes near the Venezuelan border between Colombian guerrilla groups, and between those guerrillas and the Venezuelan military, take on new significance. Smuggling and crime is a mainstay of the Colombian-Venezuelan border area. Occasional struggles over territory have been known to occur. But since the start of 2022, the neighboring states of Apure, Venezuela, and Arauca, Colombia, have seen a notable increase in violence. In January alone, Colombia’s Arauca department has registered armed clashes in the municipalities of Saravena, Tame, Fortul, Arauquita and Arauca (as well as Cubara municipality in neighboring Boyaca department). The fighting has left at least 34 people dead and has displaced nearly 1,000 more. In the most notable incident, a car bomb detonated on Jan. 20 in Saravena in an attack the Colombian defense minister blamed on a dissident FARC group. The bombing was planned in and financed by Venezuela, he said.

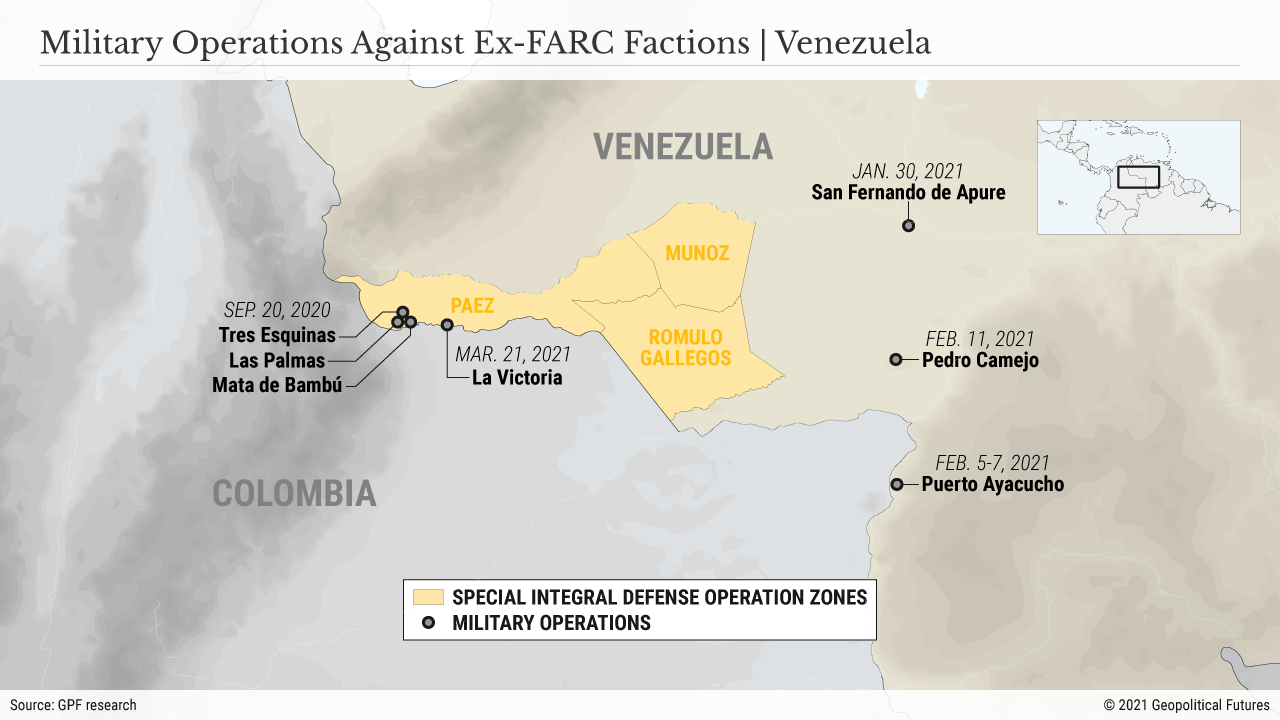

Besides the challenge the guerrillas themselves pose, the Colombian government faces the added difficulty of distinguishing them from the Venezuelan government. Several of the groups have direct ties to Maduro’s government, and many of them profit from illicit trade along the porous border and seek refuge from law enforcement in Venezuela. The National Liberation Army (ELN) has resided in Venezuela for decades and was strengthened by the dismantling of the FARC after its 2016 peace deal. With an estimated 2,500 members, the ELN has a stronghold in Apure and the support of the Maduro government, which not only ignores ELN activities but even supports the group directly via military operations. Former FARC members who rejected the 2016 deal are also still active, numbering about 5,200, and are split between three main groups: Gentil Duarte’s 10th Front, the 28th Front and Ivan Marquez’s Second Marquetalia. According to Colombia’s defense minister, the ELN and Second Marquetalia have aligned in a war against Duarte’s 10th Front and the 28th Front for control of territory and drug routes.

Why does this matter? First, because of the risk that the skirmishes could balloon into a proxy battle between great powers. In March 2021, a Russian soldier was reportedly involved in a Venezuelan military operation against a dissident FARC group in Apure, Venezuela. There are also unconfirmed reports that Russian private military contractors have trained Venezuelan troops. On the other side, the ELN claims that the 10th and 28th fronts are coordinating with Colombian and U.S. authorities, including the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. In November, the U.S. designated both the Second Marquetalia and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army – which includes the 10th and 28th fronts – as terrorist groups, but from Cold War history we know this doesn’t preclude the possibility of collusion.

A second concern is the nature and targets of the violence. Last June, a dissident FARC group attacked Colombian President Ivan Duque’s helicopter with small arms fire at Camilo Daza Airport in Cucuta. Earlier that month, the group detonated a car bomb inside a military base in Cucuta, injuring 36 people, including a few U.S. advisers. In both cases the Colombian government said funding and plans for the attacks originated in Venezuela. But even in the wake of the Cucuta car bombing, the U.S. took no major overt action; its only public response was to send the FBI to support the investigation. Months later, in September, Colombia arrested two Venezuelan soldiers on its territory. Bogota also raised the alarm about Venezuela violating its airspace – a fairly common occurrence.

And yet, both Venezuela and Colombia have kept their emotions in check. The reason is that neither is interested in a larger conflict with the other right now. The most notable action so far came when Colombia decided in October to send 14,000 security personnel to the border, primarily the Norte Santander department. Smaller security reinforcements were more recently dispatched to Arauca. Similarly, Venezuela has deployed more military assets in Apure department to support its allies among the Colombian guerrillas and to quell its opponents. Bogota and Caracas have endured periods of extreme domestic violence and instability, during which the neighboring country proved to be a good recourse for people in search of safety (and economic opportunity). A war would mean rupturing this mutually beneficial arrangement.

Moreover, direct conflict risks drawing in the U.S. and Russia. And while Bogota and Caracas value their relationships with Washington and Moscow, respectively, neither wants to enter a conflict where they would be at the mercy of their more powerful sponsors. Instead of a Colombia-Venezuela issue, it could transform into a new frontline between the U.S. and Russia. This unstable arrangement works for now, but the risk of a proxy conflict grows the longer the Venezuelan-backed guerrilla groups remain active in Colombia and U.S.-Russian relations remain tense.