At that time, access to European funding led to superficial short-term growth in the agriculture sector since growth was dependent on subsidies rather than driven by the market. This created the foundation for inefficiencies. As more countries joined the EU, funding was diverted to poorer nations, and these inefficiencies became more apparent.

In the secondary sector, the U.K. actually had less incentive to participate in trade with other EU nations than prior to membership. A number of non-tariff barriers related to continental Europe’s production standards existed and, later on, barriers stemming from use of the common euro currency, all of which diminished the U.K.’s appetite for innovating to sell on the EU market.

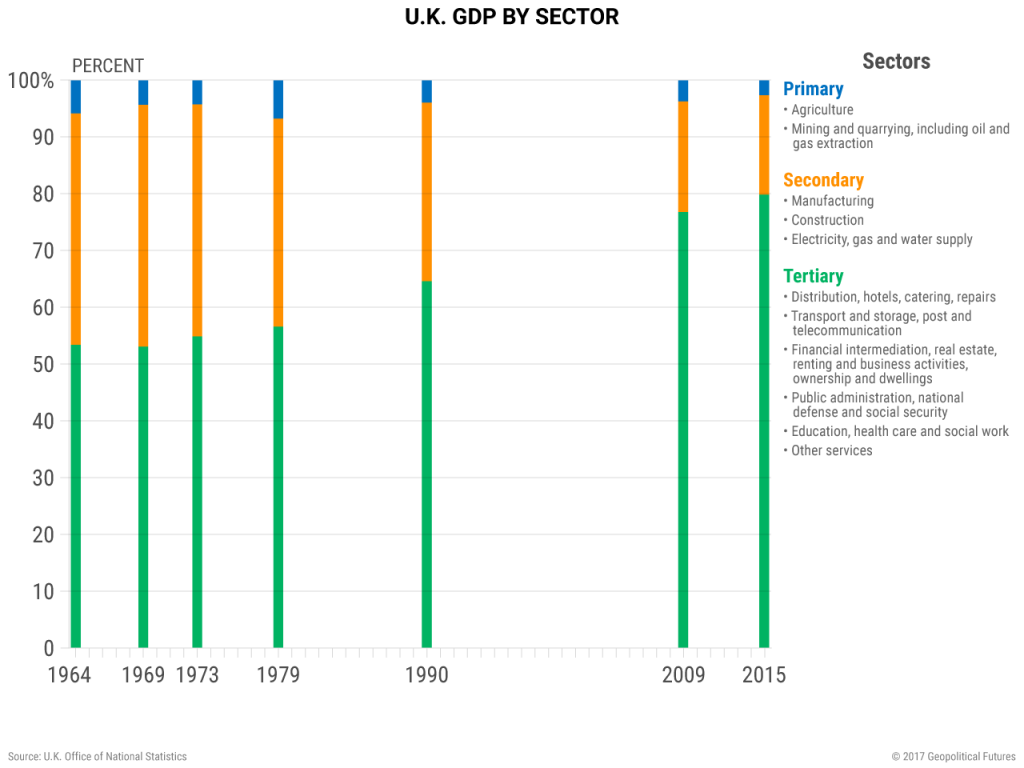

This has resulted in the British economy’s deindustrialization and an increased specialization in the tertiary sector, services. The services sector has seen constant growth since the 1960s. Finances and banking, distribution, insurance, transportation and other services currently account for more than 75 percent of GDP, and their export share is 12 percent. One of the more lasting impacts the EU will leave on the U.K. post-Brexit is this shift in economic structure.