For years, Turkey has pursued an ambitious agenda, expanding its influence in countries and regions formerly under Ottoman control. It may not be able to absorb these regions as part of its territory as its predecessor once did, but it is increasingly defending its economic, political and strategic interests in areas far beyond its own borders, including in parts of North Africa and the Horn of Africa. Here, Turkey’s goals are wide-ranging. It needs to secure access to vital maritime routes through the Red Sea and to energy resources in the eastern Mediterranean. With economic expectations among average Turks rising, Ankara also sees these regions as a gateway to emerging markets and resource hubs in the Sahel – which can encourage further economic growth. But it also faces a number of constraints, particularly competition from its rivals in the Middle East, that may limit its influence in the Arab world.

Turkish Imperatives

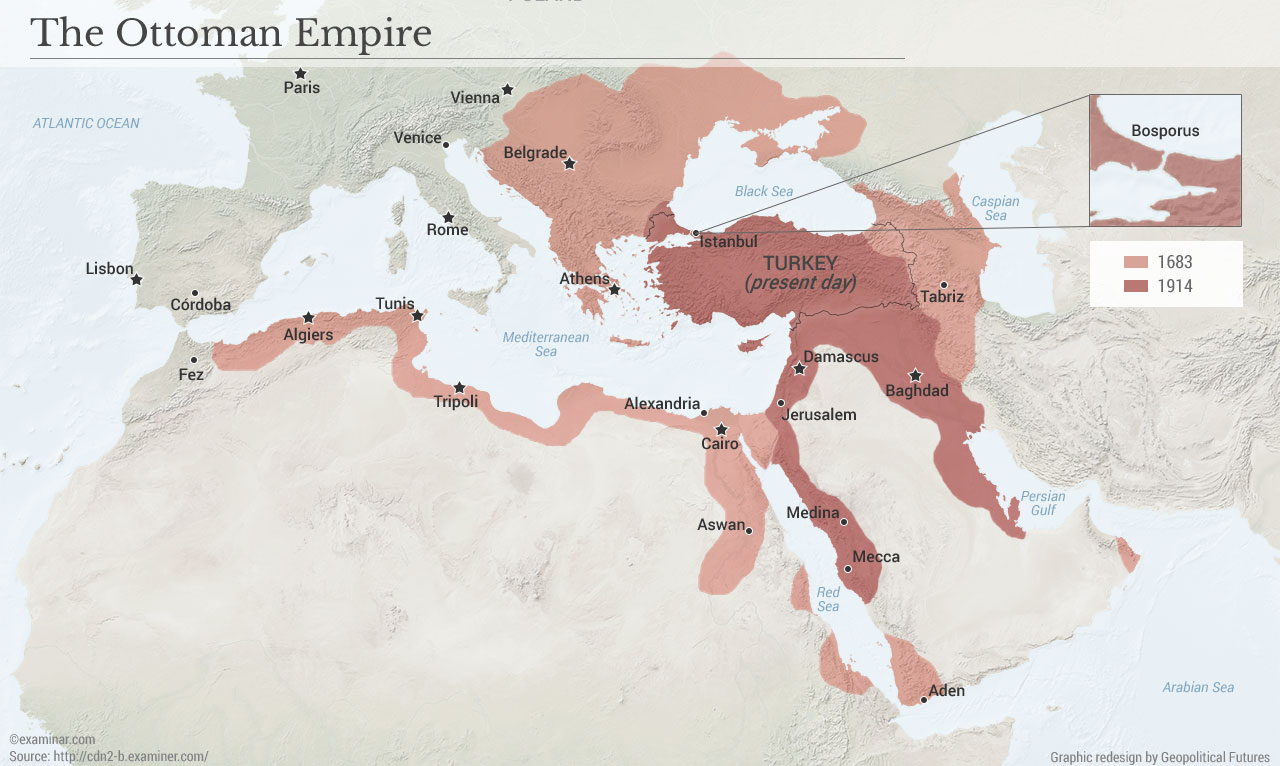

Turkish history seems to give its leaders good reason to set their sights high. The Ottomans, after all, oversaw an empire that, at its height, ruled parts of Europe, the Middle East and North and East Africa. This effectively gave the Ottomans control over many of the world’s most important trade routes and some of its most resource-rich regions. However, the empire crumbled in 1918 after the First World War, in which it backed the losing side, and its territories were divided among Britain, France and Russia. Following the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, Turkey seemed to accept its fate as a far more modest power, but memories of its past glory never faded completely.

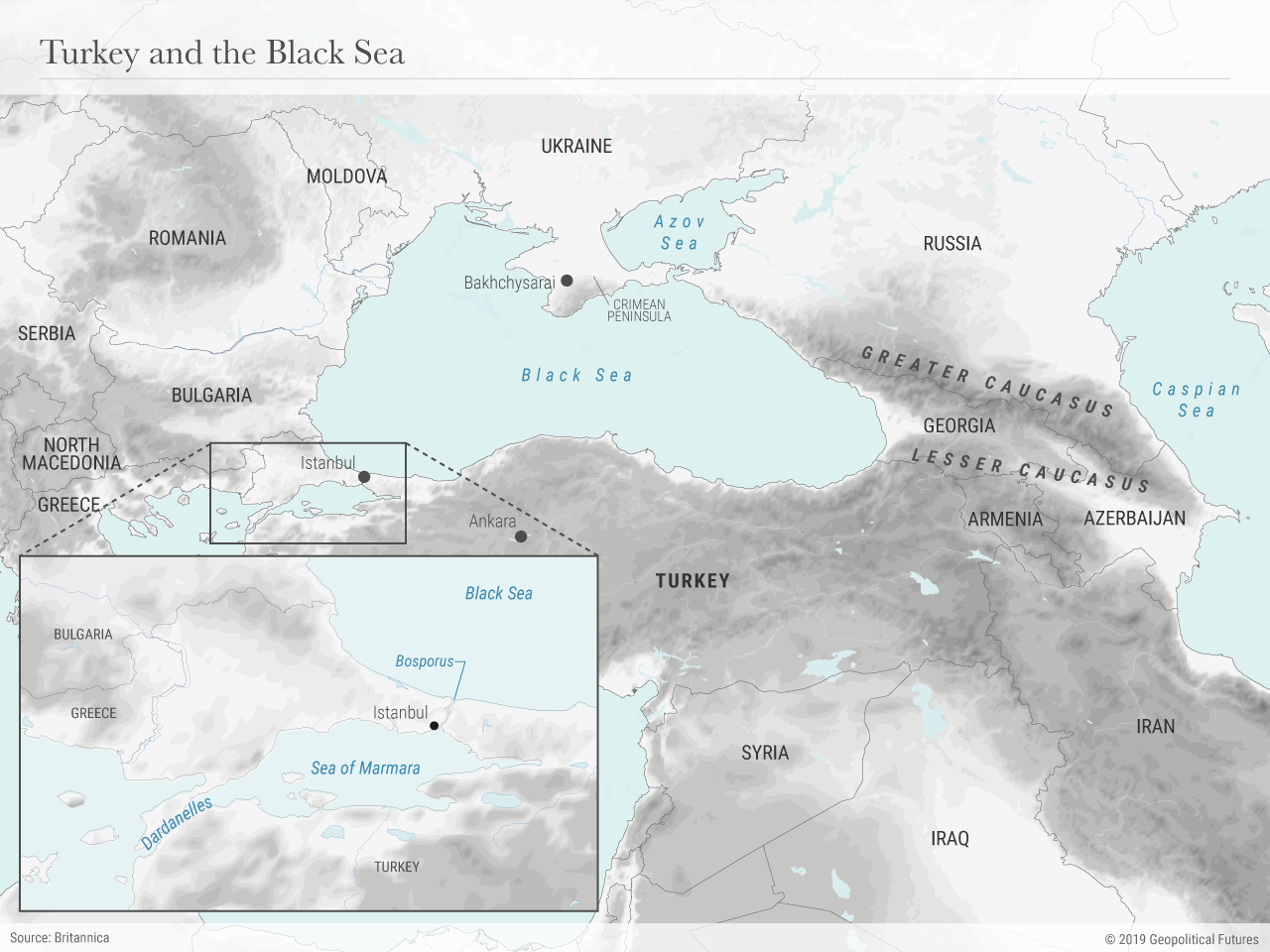

One of Turkey’s biggest sources of strength is its control over the Sea of Marmara, which effectively gives it control over the Bosporus, a critical waterway separating the European and Asian parts of Turkey and connecting the Sea of Marmara to the Black Sea. Access through the strait is key for the transportation of oil, wheat and other goods to Europe from Asia. It forces Black Sea coastal countries, particularly Russia, to avoid direct confrontation with Turkey, or else potentially lose their ability to conduct trade with Europe through the Mediterranean.

One of Turkey’s biggest weaknesses, however, is the presence of countless Greek-controlled islands that lay in the Aegean Sea beyond the Sea of Marmara and another critical waterway, the Dardanelles. These islands could restrict Turkey’s access to major sea lanes, making the country vulnerable to a possible blockade or even an attack by other maritime powers. Its other major weakness is its lack of domestic energy resources that could sustain its industrial power ambitions, making its economy highly dependent on energy imports. This is why Turkey has in recent years become increasingly forceful in asserting its claims to hydrocarbon deposits in the eastern Mediterranean.

Turkey in North Africa

Turkey’s expanding interests in the Mediterranean led to its growing involvement in North Africa. Ankara relies primarily on political engagement to increase its influence there. Though it has a naval presence in the Mediterranean, the Turkish navy is weak compared to the navies of other global powers that patrol the sea. It’s currently undergoing an ambitious modernization drive, but any progress will be slow, especially considering Turkey’s weak industrial base and procurement budget. Moreover, many of its Mediterranean rivals have the backing of more powerful allies that can help defend their competing claims in the sea. Greece, for example, has maritime defense pacts with France, Italy and Egypt. Thus, Turkey’s current operational capabilities are mostly limited to the Aegean and southern Mediterranean.

Since it can’t rely on brute force, Turkey is attempting to expand its influence by taking a page out of the Ottoman playbook. After the Ottomans seized control of parts of North Africa in the 15th century, they relied, at least in part, on local proxies to maintain power. (It also helped that the Ottomans had a comparably powerful navy.) Today, Turkey is trying to build leverage in the region by supporting allied Islamist regimes – some of which rose to power following the Arab Spring, a series of pro-democracy uprisings across the Arab world. In Egypt, for example, Turkey provided financial and technical support to help bring the Muslim Brotherhood to power in 2012. In Tunisia, it provided funding and other support for the Islamist Ennahda party, which won a parliamentary majority in 2011. These moves alarmed its geopolitical rivals, especially Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, which see Turkey’s attempt to spread its brand of political Islam to the Middle East and North Africa as a threat to their monarchical systems and leadership over the Sunni Muslim world.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE responded by forming a strategic alliance, at the center of which was a united foreign policy that strived to alienate their main rivals: Qatar, Turkey and Iran. Saudi Arabia and the UAE viewed these countries as threats to their interests – including their desire to stop the spread of democracy in the region, which could lead to the election of Islamist regimes like the Muslim Brotherhood. In Egypt, they took advantage of the Brotherhood’s inability to consolidate power and the worsening economic and security situations in the country, all of which eventually led to protests calling for the ouster of the Brotherhood-led government. The demonstrations culminated in a coup in 2014 led by then-Egyptian army chief Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi, who received financial support from Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The Saudis and UAE deployed the same tactics recently in Tunisia, where protests erupted in July over the economic crisis that has proliferated under the Ennahda-led government. Following the demonstrations, the country’s president, who was supported by the Saudis and UAE, suspended parliament and dismissed the prime minister.

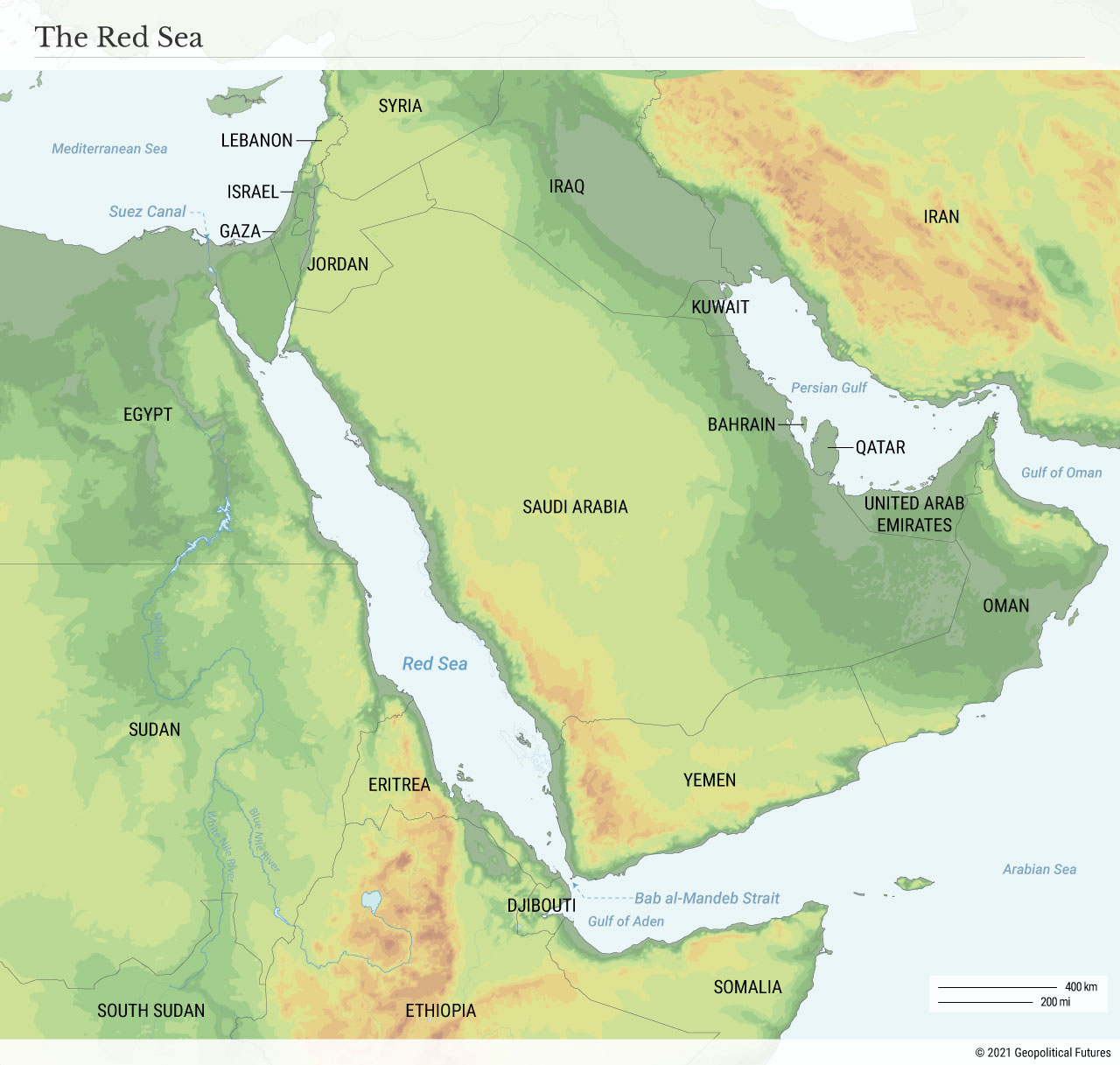

The Saudis and UAE fear Islamist groups like these, when put in positions of power, could provide a safe haven for Islamists and terrorists groups closer to home, particularly in Yemen, where Riyadh is already at war with the Iran-backed Islamist Houthi rebels, who seized the capital, Sanaa, in 2015. Turkey, on the other hand, viewed the elections of Ennahda in Tunisia and Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt as an opportunity to gain a foothold in strategic countries along the Mediterranean coast.

Turkey in the Horn of Africa and Sahel

Turkish influence has also been growing in the Horn of Africa. The Horn of Africa is adjacent to one of the busiest trade routes in the world, from the Indian Ocean to Europe through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal, passing the Bab el-Mandeb strait between Djibouti and Yemen. This means, if it wants to control its fate, Turkey will likely eventually have to maintain a robust naval presence here to secure the passage of its commercial and military vessels from the Middle East and Europe to North Africa in addition to power projection in the Horn of Africa.

Despite its current limitations, Turkey is attempting to lay the groundwork for such a force. For example, it tried to revive the Suakin port, a defunct commercial and military base along Sudan’s Red Sea coast. Suakin was a major port for the Ottoman Empire when it ruled Sudan in the 15th century. However, after Sudan’s military ousted pro-Turkish leader Omar Bashir following widespread protests against his autocratic rule, the new Sudanese regime suspended the revival project in April 2019. The new regime did not want to be viewed as puppets of Ankara. Nevertheless, Turkey and Sudan still have warm ties, and the two countries signed a memorandum of understanding to boost cooperation in banking, energy and defense in August 2021.

Ankara has had to focus mostly on soft power to advance its interests in the Horn of Africa, but even this approach has its limits. Turkey has prioritized trade and investment relations with the region’s largest economy, Ethiopia, with Ankara being the third-largest foreign investor in the country behind China and Saudi Arabia. But when Turkey tried to wield its influence and offered to mediate a border dispute between Ethiopia and Sudan, presenting itself as an alternative to the U.S. in the Horn, Addis Ababa rejected the offer.

Somalia represents the only success story so far for Turkey in the region. Ankara is the dominant foreign actor in Somalia and has been able to ward off attempts by the Saudi-UAE anti-Turkey alliance to displace it. Ankara’s extensive economic aid to Somalia when it was facing a devastating famine in 2011 earned it goodwill in the country. Ankara used this political capital to support local allied groups, particularly Islamist groups. Turkey opened a military base in Mogadishu in 2017, the largest of its kind outside of Turkey, to train Somali troops. It has also established a firm foothold in Somalia’s airports and seaports, which it views as critical for power projection across the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. Thanks to its efforts, when the UAE made financial overtures to try to convince Somalia to cut ties with Turkey and Qatar, the Somali leadership refused.

Nevertheless, Turkey’s economic problems are still a major constraint on its actions in the Horn. Its main problem is that its currency, the lira, is in continuous freefall, resulting in rapidly rising inflation. Turkey’s adventurism has also made it the target of U.S. and EU sanctions. In October 2019, Ankara launched military offensives against U.S.-allied Kurdish forces in Syria. It also detained an American citizen whom it accused of supporting a 2016 failed coup against Erdogan. And its illegal gas drilling in Cypriot waters prompted sanctions from Brussels. Western sanctions directly affected Turkey’s steel and aluminum industries. Exports plummeted, and the Turkish lira fell by 10 percent.

The prolonged economic struggles have alarmed investors, who worry about political interference affecting monetary policy as well as the country’s rising foreign debts. This is a problem for Turkey because it needs outside investment for its industrial economy. Erdogan has therefore been trying to improve ties with the U.S and other geopolitical rivals, notably the UAE, to regain the confidence of investors. Erdogan held a bilateral meeting with U.S. President Joe Biden in June, during which he declared a new era of relations based on positive and constructive ties with Washington. He also said in August that Ankara wants to have a good relationship with the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

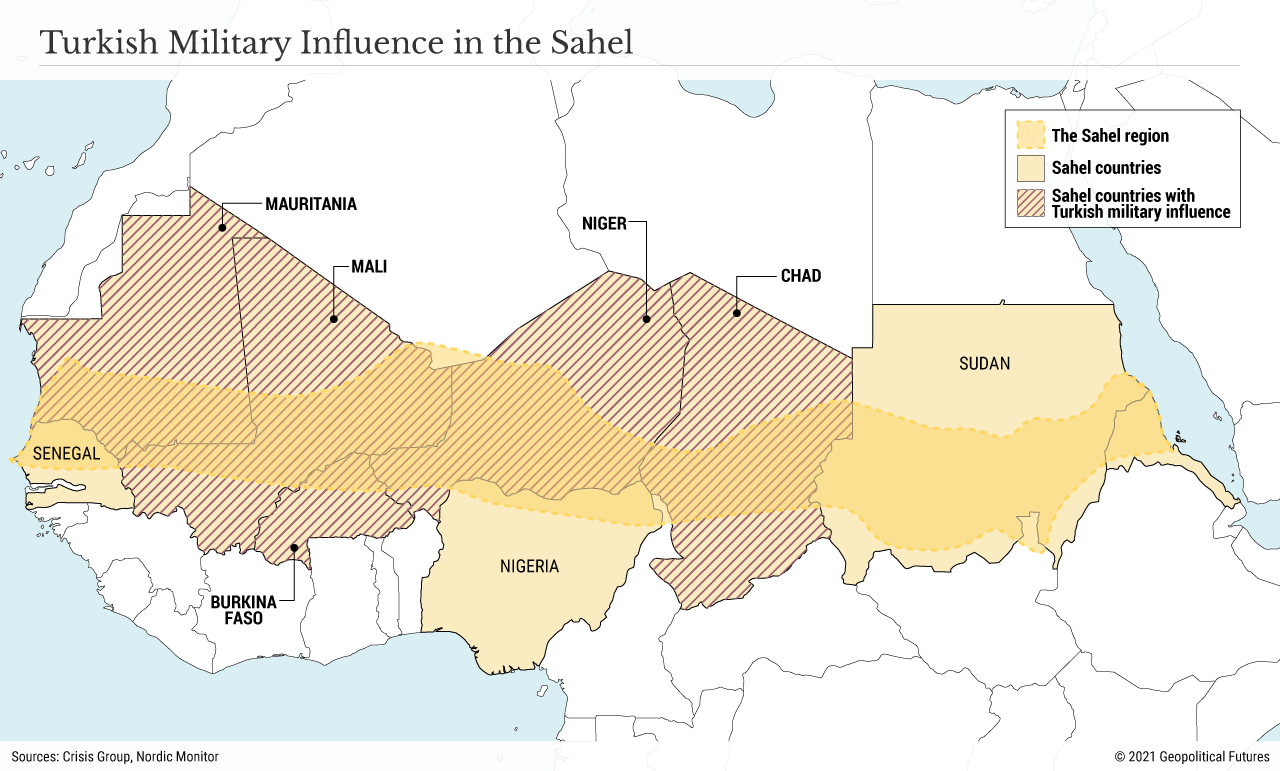

And this is where the Sahel enters the Turkish strategy. Turkey sees the Sahel as a place to expand trade and acquire natural resources needed for its industries. While Turkey’s motives are primarily economic, its strategy includes a significant security and military component. This is necessary because any foreign actor hoping to engage with Sahel countries must gain influence and trust by proving it is capable of helping them address their security challenges. Turkey can do this because of its growing defense industry.

Turkey’s strategy in Somalia provides a blueprint for how Ankara plans to pursue its interests in the Sahel. In short, the Somalia model consists of propping up allied local groups. Turkey hopes to take advantage of growing anti-French sentiment and France’s shrinking presence in the Sahel to present itself as an alternative security partner. It could then use its newfound political capital to partner with local groups and flood markets with Turkish-made weapons and other goods. Such partnerships would also help Turkey access and secure the region’s rich natural resources for its industries. These extractive projects also attract the interest of insurgent and criminal groups, so they often require a strong security component. This is why Turkey pursued military cooperation agreements with Sahel countries like Niger, Mauritania and Burkina Faso.

Turkey’s ability to wield influence in West Africa and the Sahel is significantly constrained by established powers in the region such as the U.S., France and China. Then there are emerging powers in the region like Russia, which has already deployed mercenaries to support friendly regimes and protect the Kremlin’s interests. Ankara hopes to counter this by calling on Islamic solidarity. The majority of the citizens in the region practice Islam, so it would bankroll projects casting Turkey as the custodian of Islamic culture, like building mosques and hospitals in Sahel states like Mali and Niger. This would help Ankara build close ties with local communities, contrary to Moscow’s elite-based diplomacy, which focuses on close ties with incumbent national leaders.

Turkey’s broad strategy in Africa is focused on recreating a neo-Ottoman sphere of influence in North and East Africa. Turkey is eying energy exploration and vital sea routes for trade with sub-Saharan Africa and the Sahel, where it hopes to secure raw materials to bolster its ailing economy and eventually become a leading industrial power. However, Turkey must overcome its ailing economy, relatively weak navy and the activities of its geopolitical rivals in these areas.