By George Friedman

Since World War II, the foundation of Japanese national strategy has been reliance on the United States to protect Japan’s national interests. The U.S. ensures that sea lanes supplying Japan with essential raw materials stay open. It guarantees Japan’s physical security – against threats from the Soviet Union during the Cold War, and from China thereafter. And it gives Japan access to American markets, first during its financial recovery from the war and then as part of its development into the world’s third-largest economy. In return, the Japanese accepted the presence of American forces in Japan, providing a base of operations designed to preserve the control of the Northwest Pacific that the U.S. attained during WWII. From those bases, the U.S. could block the Soviet fleet in Vladivostok, support operations in South Korea and so forth.

Those were the direct benefits, but indirectly Japan received an additional perk: absolution from participating in U.S. conflicts. The U.S. had crafted a post-war constitution for Japan that prohibited it from developing a military. Much as with Germany, the sense was that the permanent disarmament of Japan was essential to prevent the re-emergence of a militaristic country. And as with Germany, the U.S. came to regret this principle. As the American strategy of containment took shape against the Soviet Union, the U.S. wanted a rearmed Germany to block Soviet moves in the west. Similarly, as the Korean War broke out, the U.S. wanted Japanese military force to assist it. Japan helped with essential military production – trucks, for example – but it held on to Article 9, the provision in its constitution that prevented it from forging a military to fight in Korea.

Later, Japan reinterpreted Article 9 from an absolute prohibition on military force to an absolute prohibition on an offensive military force. Then, as its military force developed, Japan redefined the meaning of an offensive force to focus not on the nature of the force but on the nature of its utilization. A destroyer or fighter plane is by its nature an offensive weapon, but Japan decided that so long as such weapons were not used offensively, their existence was constitutional. Using this logic, Japan has developed a substantial military force that it withholds from any offensive operation, although it has used it in some peacekeeping operations.

Japan has therefore avoided operational deployment in U.S. wars, from Korea and Vietnam to Iraq and Afghanistan. At the same time, it has developed a significant naval and air force, and it is capable of becoming a nuclear power at will, given that it has one of the most sophisticated civilian nuclear programs in the world. One joke goes that Japan does not have a nuclear weapon because a single screw needed to enable it has not been tightened. That may overstate the hurdles but it captures the principle. The limit of Japanese military power is Japan’s will.

On the whole, the U.S. has been content with this arrangement, even if it is occasionally frustrated by Japan’s posture as an ally. The strategy worked great for Japan for more than 70 years, until the balance on the Korean Peninsula showed signs of changing. At first, as the nuclear threat in North Korea grew, the United States became more alert and aggressive toward the threat. The South Koreans supported an aggressive American policy, and the pro forma call for the Chinese to reason with North Korea did not yield a solution. The U.S. threatened military action to destroy the North Korean weapons, and though Japanese bases might be used, Japan would not be involved militarily.

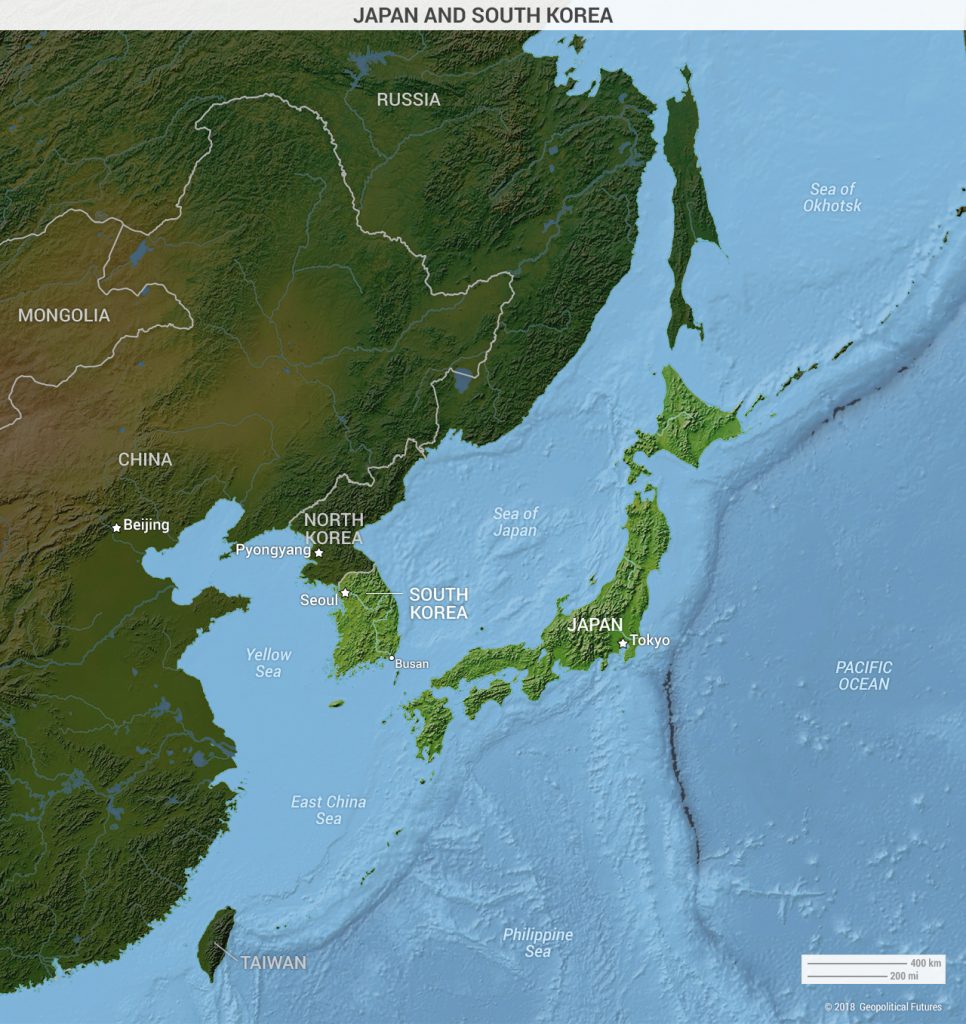

But Japanese strategy began to go off the rails recently with an attempt at rapprochement between North and South Korea. In its pre-World War II strategy, Japan had long viewed the Korean Peninsula as a buffer between itself and the mainland. The Japanese occupied the peninsula to ensure that this buffer remained. After the war, the division of the peninsula and the American presence in the south guaranteed the buffer. But then last year’s Olympic rapprochement happened, and it altered a significant strategic assumption of the Japanese: that the status quo was a given. There suddenly existed the potential for an accommodation between North and South and even potentially, over time, increased Chinese influence there. Even as a distant and unlikely possibility, this was a serious problem for Japan. If the U.S. would accept an understanding between the North and South, and if that understanding included the withdrawal of some or even all U.S. troops from Korea, then the strategic balance would shift.

Japan would lose its buffer against China. The Sea of Japan, not the Yellow Sea, would become the naval focus, and with U.S. interest in the region declining, it would be the Japanese navy that would have the primary mission of controlling the Sea of Japan. North Korea could give up its intercontinental missiles, which threaten the U.S., but keep its shorter-range missiles capable of reaching Japan, and thus Japan would have to openly create its own nuclear deterrent. And depending on the extent of the U.S. retreat from the region, Japan may no longer be able to rely on the U.S. to guarantee its access to raw materials.

And Japan’s concerns are not utterly far-fetched. South Korea has an overriding imperative to avoid another war on the peninsula. The U.S. does not want intercontinental ballistic missiles in North Korea, but it might accept a deal permitting short-range missiles. And though neither North nor South Korea really trusts the Chinese, a U.S. retreat from the region might require some accommodation with China.

Obviously, this scenario has yet to play out, but the Japanese have made it clear to anyone who will listen that the direction of accommodation is unacceptable to them. And this is where Japan runs into the trap embedded in its national strategy. Depending on its relationship with the U.S. to both protect it from major threats and excuse it from significant offensive action, the Japanese force, though far from insignificant, does not give Japan the weight to change the course of the negotiation. China has the potential to do so. The U.S. does as well. Japan does not.

Charles de Gaulle warned the world of this type of problem. The ultimate guarantee during the Cold War was that, if needed, the U.S. would escalate to nuclear war to block Soviet advance. De Gaulle argued, however, that the U.S. would not trade New York for Paris. Now Japan must ask itself how far the United States would go to maintain its position in the Northwest Pacific. The region is important to the U.S., but likely not important enough to warrant a nuclear exchange. The U.S. can exit and survive. Japan does not have the luxury.

For the first time since World War II, Japan must consider whether the strategic reality in its region could evolve in a direction “not necessarily to Japan’s advantage,” to quote Hirohito’s surrender speech in 1945. Such a shift would require Japan to rethink how it sees itself and its role in the world. Nothing may change. Indeed, with less than three weeks to go until the scheduled Kim Jong Un-Donald Trump summit on June 12, the U.S. is already suggesting there’s a “substantial chance” talks won’t happen in June. But if reconciliation happens, Japan may not have time to create the military force it will need to defend its interests. Japan cannot wait until there is clarity, nor can it proceed without a political crisis. Japan is trapped between a new reality and its old strategy.