The Arab uprisings briefly resurrected the idea of Arab nationalism. During the 2011 Pan Arab Games in Qatar, spectators sang the unofficial Arab national anthem, the lyrics of which promote the idea that Arabs cannot be separated by artificial borders or religion because the Arabic language unites them all. But the euphoria of the moment soon dissipated, as the reality of factionalism set in. Despite various attempts at unity, Arab nations have time and again failed to act collectively or agree on common interests.

False Beginnings

The first Arab nationalist movement was launched in Beirut in 1857. The Syrian Scientific Society ushered in a short-lived Arab cultural and intellectual renaissance. Failing to attract a broad audience, it fizzled out as the First World War began. It was essentially an elitist organization of primarily Syrian and Lebanese Christians and a few Americans and Britons living in the area. (Secular Arab nationalism appealed to Christians because it meant they could be integrated as full-fledged citizens.) Decades later, the Young Arab Society was established in Paris in response to the 1908 Young Turks’ coup against Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid. The group demanded a democratic transition, administrative autonomy for Arabs and the designation of Arabic as an official language on par with Turkish.

The repressive policies of the Ottoman military governor of Syria led the Young Arabs to demand independence for the Arab provinces in West Asia, paving the way for the British-backed Great Arab Revolt in 1916. The world order that emerged after the First World War gave rise to the present-day states of the Arab East, while the independent countries of North Africa emerged in the aftermath of the Second World War. Western imperial countries created the Arab states in their current format to ensure their continued fragility and dependence on the West for their security.

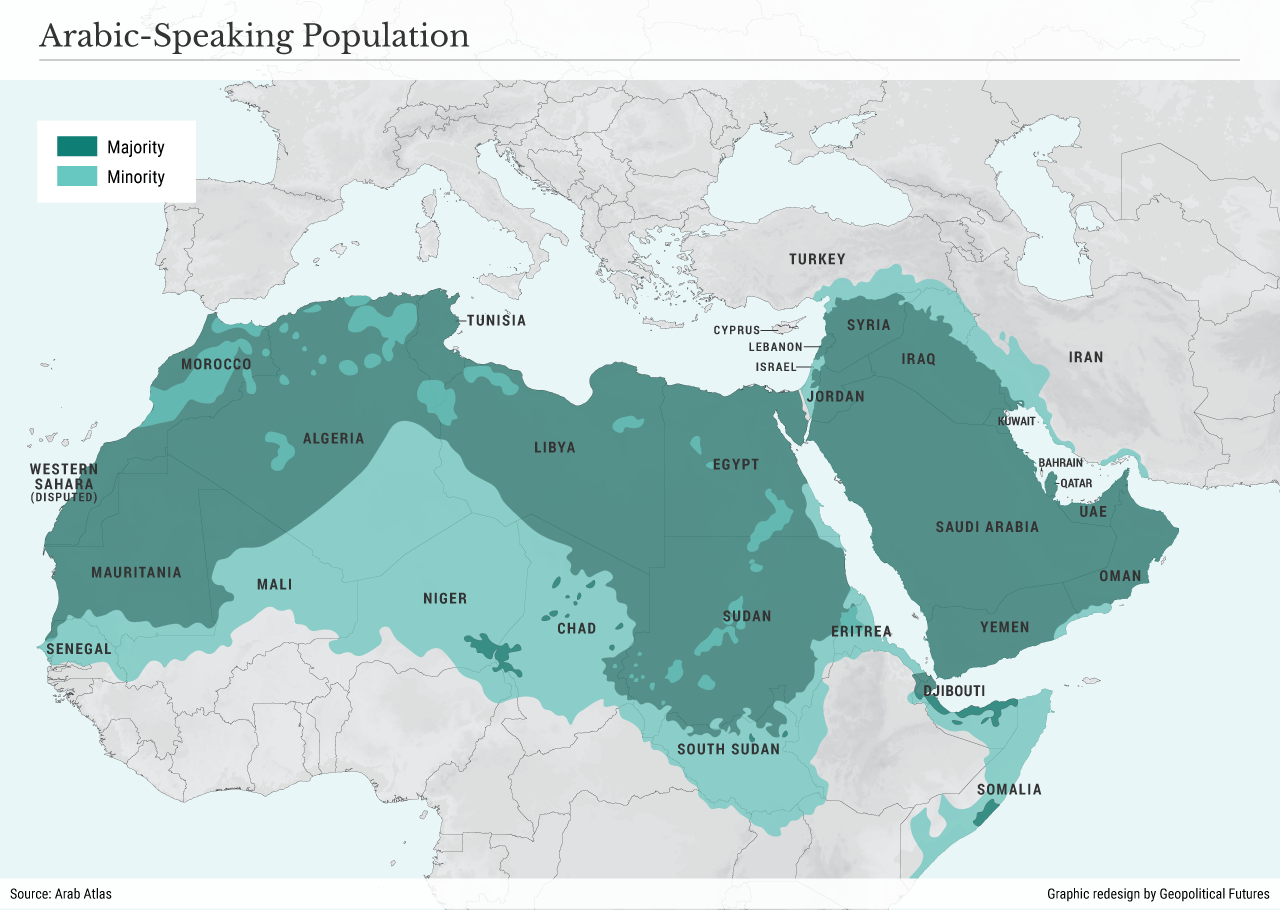

Arab identity is not an ethnic marker. It emerged during the Abbasid caliphate as a political dividing line between Arab caliphs and their Persian subjects in the ninth century. To be considered an Arab, it was sufficient to claim to be one and to speak the Arabic language. Arab nationalism was mostly limited to pride in the community’s achievements, especially the spread of Islam and the Arabic language outside the Arabian Peninsula. Arab regimes’ obsession with staying in power prevented them from cooperating, ensuring that state nationalism superseded pan-Arabism.

The Myth of the Greater Arab World

The idea of the Arab world – a region extending from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Persian Gulf in the east and the Indian Ocean in the south – was introduced in the early 20th century by Sati al-Husary, Iraq’s minister of education during the reign of King Faisal I. At the time, his conceptualization of Arab nationalism remained mostly a sentimental attachment to religion and language. Indeed, Arabs took pride in their identity and culture, but didn’t extend their sense of unity to the economic or political realm.

In 1920, Faisal established the Arab Kingdom of Syria. A few months later, a French force – which also included Moroccan cavalry and two Algerian battalions – defeated the poorly equipped and understaffed Syrian force in the Battle of Maysaloun near Damascus, claiming Syria as a French mandate. This delivered a crippling blow to Arab nationalism, preventing Damascus from becoming a pan-Arab hub and dooming its prospects of functioning as a central state capable of influencing Arabs everywhere.

Unlike nationalism in Europe, Arab nationalism didn’t develop because of a technological breakthrough in production that ushered in an industrial age. It didn’t give rise to an inclusive political community that superseded sectarian, tribal and clannish identities. Arab leaders, hoping to win popular legitimacy, promoted public displays of Sunni orthodoxy instead of treating faith as a private matter – which alienated Islamic heterodox sects and Christians. For example, Egyptian Vice President Hussein el-Shafei, who served under President Gamal Abdel Nasser, tried to attract Egypt’s Coptic Christians to Islam. In the 1970s, Libya’s Moammar Gaddafi urged Lebanese Maronite Christians to embrace Islam to end the civil war.

Arab nationalist thought contributed to reviving religious dogma. In Sudan, for example, President Jaafar Numeiri transformed from a secular Arab nationalist to a religious zealot, introducing sharia throughout the country, including in the non-Arabized and non-Islamic southern region.

Lack of Collective Action

This factionalism and self-interest blocked any attempts at genuine cohesion. The Gulf Cooperation Council was created in 1981 by six Arab nations – Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait and Oman – ostensibly to integrate their economies and defense capabilities. But the group failed to achieve its stated objectives, and relations among the member states were marred by conflict. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are still entangled in ongoing border issues. And in 2017, three of the member states (plus Egypt) imposed a three-year blockade of Qatar.

The idea of establishing the Arab Maghreb Union – an alliance among Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, Mauritania and Libya – appeared in 1956 after Tunisia and Morocco won independence from France. But this too failed to inspire a sense of unity. Morocco’s invasion of Algerian-held territory in 1963 started the Sand War, which permanently soured relations between the two countries. Their dispute over Western Sahara further deepened tensions, and last month, Algeria severed diplomatic ties with Morocco. The five countries held their first summit in 1988, but the heads of state have not met since Algeria closed its border with Morocco in 1994. The AMU has reached 30 multilateral agreements, but only five of them have been ratified.

The 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement, which divided parts of the Fertile Crescent into French and British mandates, dampened the Arab nationalist drive. Unlike Iran and Turkey, where a strong central state promoted cohesion and solidarity, Arab nationalism did not have a country committed to advancing its cause and creating a unified pan-Arab entity. It failed to take off mainly because the core Arab states were distracted by their own problems with corruption, despotism, economic stagnation and military adventurism.

Arab nationalist movements splintered, giving rise to leftist and Marxist political parties. The Lebanese Communist Party, for example, dissociated itself from Soviet internationalism to participate in guerrilla warfare against Israeli troops in south Lebanon. George Habash, who founded the Arab Nationalist Movement in 1951, renamed it the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. This Marxist-Leninist movement orchestrated high-profile terror plots in Israel and a series of airplane hijackings in the 1960s and 1970s.

“Awakening of the Arab Nation,” a book written in 1905 by Maronite Christian Naguib Azoury, predicted a clash between Arab nationalism and Zionism – which would not end until one of the two movements defeated the other. Azoury’s prophecy came true in 1967, when the Six-Day War dashed all hope for a pan-Arab nation as concerns turned to recovering the territory captured by Israel. The defeat allowed ethnic and religious minorities in the Arab region, which had for the most part failed to articulate specific demands, to contest state authority and press for autonomy. They became militarized and presented far-reaching policy demands in Algeria, Sudan, Iraq and beyond.

Arab identity still exists in a narrow sense as a reminder of past glory and a common culture. It is a symbolic force that has no mechanism for collective action across the region. Having lived under a succession of religious empires, Arabs did not undergo a necessary transformation to facilitate the triumph of nationalism. In the Arab region, religion remains the decisive social force and the driver of collective action.