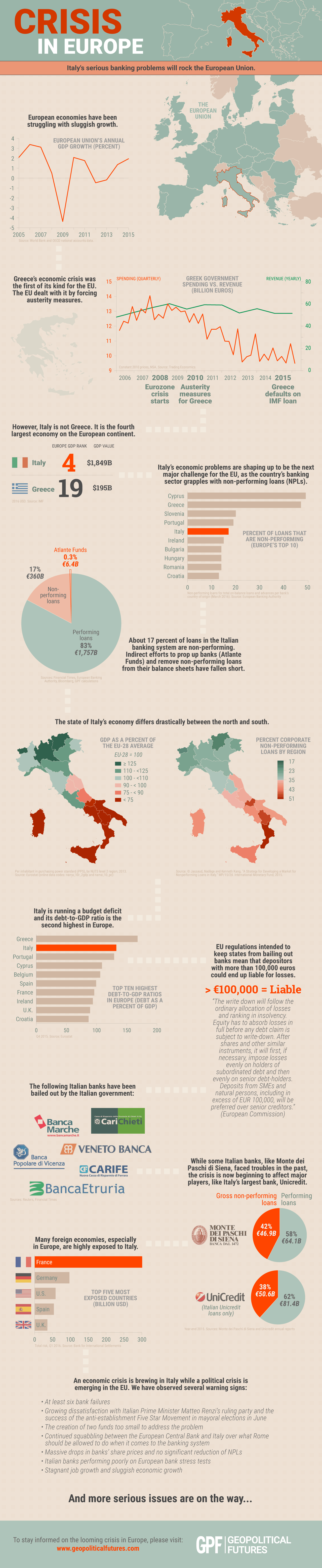

Since the 2008 global financial crisis, European economies have been struggling with sluggish growth. Mediterranean Europe in particular has faced a challenging recovery, reflected in the current staggering rates of unemployment, with some nations over 20 percent and all over 10 percent. To make matters worse, the world currently finds itself in the midst of an exporters’ crisis, which has been unfolding to the point where it appears that a worldwide recession is beginning. Global economic growth forecasts along with estimates for worldwide trade growth have been lowered multiple times throughout the year.

The first economic crisis to test the fundamental cohesion of the eurozone was the Greek economic crisis. Germany largely dictated how this crisis was to be handled because it is the largest economy in Europe and the fourth largest economy in the world. Berlin faced a double-edged sword when looking for solutions to the Greek crisis. On one hand, Germany cannot afford to unilaterally solve the Greek problem, as it would set a precedent Germany cannot live with. It must compel the Greeks to be primarily responsible for its own debts. On the other hand, it cannot afford to see Greece default or leave the European Union. Germany relies on the European free trade zone for nearly half of its exports, and total exports account for almost half of Germany’s GDP. It is terrified of a breakdown in the eurozone. Default would lead Greece to leave the eurozone, which would then set a precedent for leaving the free trade zone.

The Crisis in the South

This year, Germany has been confronted with a farm more daunting challenge: the economy of Italy. Italy is a $1.8 trillion economy and the fourth largest in Europe. The size of the Greek economy pales in comparison. Italy already has a major unemployment problem in the south. It is now facing a rising rate of non-performing loans (NPLs) – loans that are not being paid back. Italy’s NPLs now total an estimated 360 billion euros (about $395 billion) and show no signs of significantly reducing in the near future.

It should be noted that the source of Italian NPLs is overwhelmingly corporate. According to a 2015 International Monetary Fund paper, 80 percent of Italian NPLs were in the corporate sector. Moreover, the regional average for corporate NPLs is above 30 percent, and in some southern regions in Italy exceeds 50 percent. This is not a problem confined to a few individual borrowers. This is a larger issue affecting small and medium-sized enterprises that provide jobs for a large part of the economy of Italy. It is a systemic issue, and though it is far worse in southern Italy, it is not confined there.

The Italian government has spent the year searching for potential ways to avoid a massive breakdown in the financial system. Failure to succeed in this endeavor means economic failure and greatly increases the risk of political failure. Unemployment in at least four of Italy’s southern provinces is over 18.8 percent and in the other southern provinces is between 12 percent and 18.7 percent, according to Eurostat. Disillusionment with the Italian government is growing and the crisis has also raised the deeper question about whether Italy should stay in the European Union. These issues will likely come to a head in a Dec. 4 public referendum in which Italians will vote on constitutional changes to restructure the government in a way that is supposed to facilitate the government taking action to address the economic crisis. Prime Minister Matteo Renzi has previously said he would resign if he lost the referendum.

What Are Italy’s Options?

The argument for staying in the EU will be that Italy can’t get better without the EU. The argument for leaving the union will be that Italy will never get better if it stays. In any case, the malaise that has gripped the economy of Italy for years will continue, and it is important not to expect solutions in a matter of weeks. The question is whether this is the permanent condition of Europe.

A solution to the Italian banking crisis is becoming more and more urgent. The problems are that, given Europe’s track record, speed is unlikely and the Italian crisis has proved far more challenging than the Greek one. Compounding the complexity of the issue is that the solution to this crisis does not only have economic consequences, but political consequences throughout the entire eurozone.

The current Italian banking crisis carries with it the possibility of bank failures. The consequences of these failures pyramid the crisis because of European Union regulations. Essentially, the position of the European Union is that the European Central Bank (ECB) and the central banks of member countries cannot bail out failing banks by recapitalizing them – in other words, injecting money to keep them solvent. EU regulations go so far as to prohibit Italy from using its state funds to shield investors and shareholders of banks from losses, unless there is risk of “very extraordinary” systemic stress. Rather, the European Union has adopted a bail-in strategy.

Making Investors Out of Depositors

The bail-in strategy is in theory a mechanism for ensuring fair competition and stability in the financial sector across the eurozone. It protects countries, like Germany, from spending their money on bank failures in other countries, and keeps the ECB from printing extra money and exposing Europe to inflation that would reduce the position of creditors. The fear of inflation is remote at the moment but it still is an institutional principle of the ECB. And controlling national expenditures on banks imposes fiscal discipline on countries that seek to bail out not just banks, but the equity holdings of investors, who will lose their investment when the bank fails.

The issue is this: who is considered an investor? In the view of the EU, depositors are, in cases of a bank resolution, investors in the bank. The bail-in process can potentially apply to any liabilities of the institution not backed by assets or collateral. There is some insurance available, and there are EU regulations on deposit insurance, but there is no EU-wide system of deposit insurance. This is because creditor nations do not want to share the liability for bank failures in other nations. This means that while the first 100,000 euros in deposits are protected, in the sense that they cannot be seized, any money above that amount can be.

The idea of the bail-in obliterates a distinction that has become fundamental to European and American banking since the massive banking failures of the 1920s and 1930s. It was understood that the purpose of a savings account was to find a safe haven for your savings or your operating capital. The depositor paid for the safe haven by accepting extremely modest interest rates. In contrast, an investor takes on greater risk and is responsible for evaluating the financials of an investment. The bank is an institution that is an alternative to riskier investments.

There is one tremendous consequence in this bail-in strategy. It increases the possibility of runs on banks, particularly by large depositors. As it becomes known that depositors are investors and that their assets will be forfeited to pay debtors, the bank ceases to be a safe haven.

The more aware the depositor becomes that he will be treated as an investor, the more he will behave like an investor. Realizing that his bank deposit is all risk with no upside, any indication that risks are mounting will cause a rational actor to withdraw his money, and this will increase the risk of a run and collapse.

The Economy of Italy in a Downward Spiral

Italy, EU regulators and eurozone countries like Germany now find themselves caught in a toxic cycle. The EU’s rules have limited the Italian government’s ability to provide support for struggling banks. Partly as a result, European regulators have been cautioning about the state of Italian banks. EU warnings about banks have spooked investors – the same investors that the Italian government and EU had hoped would buy tranches of bad loans under an EU-approved plan to help Italy’s banks.

Failure to effectively implement this plan has forced the Italian government to consider alternative ways to pump money into ailing banks. Some of these plans, however, may contravene EU rules. Floating these alternative proposals is further spooking European institutions and private investors, while heightening tensions between Rome and Berlin.

For example, the Italians want to run a substantial budget deficit to stimulate the economy of Italy. The EU operates under a “stability pact,” which requires deficits to be kept within certain limits, but allows for exceptions. One exception has been France, which has been operating outside the boundaries of the stability pact for years. Spain and Portugal were recently given exceptions as well. As German Chancellor Angela Merkel put it, “The stability pact has a lot of flexibility, which we have to apply in a smart way.”

In the meantime, Italy will continue to come up with homegrown solutions, knowing that the ECB may approve or reject the proposal. For example, in October 2015 the European Commission rejected an Italian plan to create a single “bad bank” that would have taken away all of the debts held by Italian banks. The twin goals in this plan would have been to encourage investment into Italy’s banks while creating a more efficient vehicle, backed by state guarantees, for selling the bad debt on the market. Italy’s broad strategy is to find a way to shift the risk from the banks to the Italian government – which is precisely what new EU regulations try to prevent.

That said, there is also the question of whether the Italian government could absorb the risk of all these loans failing. Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio is more than 132 percent, second in the eurozone only to Greece. The Italian budget passed last December is around 32 billion euros and is projected to run a deficit of 2.4 percent of GDP and exceed the previous target of 1.8 percent.

Italy has already taken steps to safeguard its ailing banking system, but Rome’s efforts have had limited impact. In November 2015, the Italian government raised 3.6 billion euros to rescue four smaller banks. It did that by getting three-year advances of 600 million euro loan installments from healthier Italian banks. The government may be able to save a few banks, such as Monte dei Paschi di Siena, which is struggling to find a buyer, but Italy doesn’t have the ability to bail out the entire banking sector. Taking out loans is theoretically possible, but the premium Italy will have to pay for borrowing money is only going to increase.

A second attempt was made this past April when the Italian government set up the Atlante fund, a 4.25 billion euro fund charged with purchasing shares of troubled lenders and buying bad debt in an effort to alleviate concerns over the Italian banking sector. Two months later, roughly half of these funds were already used to purchase Banca Popolare di Vicenza and Veneto Banca when both banks’ IPOs failed. Italy’s largest bank, UniCredit, had lost 55 percent of its value as of June and needs an estimated 10 billion euros in additional capital. The bank received 3 billion euros from the initial round of targeted longer-term refinancing operations loans from the ECB. While special government funds may address some issues in the short term, it is not enough to solve the underlying problems.

The Euro Problem

For nearly a year now, Brussels has been trying to impose strict financial targets on Italy. For years, Germany has subscribed to the policy of austerity for southern Europe. Both sides have reasonable demands. Italy wants the EU to support it in a particularly challenging time. Germany does not want to be held responsible for what it sees as another country’s profligate lending. One reason there has been such a standoff over how to solve Italy’s banking crisis is because Italy and Germany have found their interests diverging despite the fact that neither country can afford to see Italy’s banking system collapse.

However, there are now growing indications that Germany is being forced to shift its commitment to austerity. Initial indicators of this include Germany’s recommendation that the EU not fine Spain and Portugal for their excessive deficits, as well as Merkel’s recent call for the EU to show Italy more flexibility in terms of spending. Several key factors are contributing to this evolution. Germany’s export crisis, lower interest rates, the refugee crisis and political changes across the Continent have led to a change in Germany’s constraints and priorities.

Germany’s export crisis is one of the driving forces behind Berlin’s reduced focus on austerity. The eurozone is an important destination for German exports, and austerity policies – which prevented governments from adequately addressing low growth and unemployment – hurt demand for German goods. Now that the country is facing an exports crisis, Berlin must now consider the possibility that stimulus in southern economies like Italy could help revive some demand for German goods.

At the same time, despite austerity, German banks are currently facing the risk of contagion from southern European banks saddled with non-performing loans and suffering due to low growth and low interest rates. In late August, the European Commission approved plans for a 5 billion euro recapitalization of Portugal’s Caixa Geral de Depósitos, a state-owned entity and Portugal’s largest bank by assets. The plan includes a government injection of 2.7 billion euros which the EU has agreed not to consider state aid. European authorities are showing great flexibility on banking and budget rules for Portugal because they fear contagion from Portugal’s ailing banking system that is still saddled with 33.7 billion euros worth of NPLs, representing 12 percent of total loans. This not only sets precedence within the eurozone but also opens the door for discussion on how more flexibility can be demonstrated towards the Italian government.

Lastly, the refugee crisis has also contributed to the decline of austerity politics, as the vast majority of asylum seekers arrive in two key southern European economies – Italy and Greece. While arrivals to Greece have been declining, in part due to the EU’s deal with Turkey, refugees continue heading to Italy in large numbers. Thus far in 2016, 165,409 people have arrived in Greece and 129,126 in Italy. The continuation of the refugee crisis and its disproportionate impact on southern Europe are giving the region’s governments ammunition in their negotiations over austerity.

Southern Europe’s economies, like the economy of Italy, are fragile, and the decline of austerity politics does not mean that the problem of debt is going away. Haggling between governments and Brussels over budgets will continue, and some political forces in Berlin will still prefer to see spending cuts in southern Europe. But fiscal health and spending cuts in the region are gradually taking a backseat as German leaders turn their attention to the export crisis, banking stability, refugee issues and the rise of anti-establishment parties. In the long run, this may be a risky choice, and for some countries austerity could come back with a vengeance. But as Europe fragments, EU members – and Germany in particular – will become more flexible on issues like austerity as they race to address pressing crises and keep the bloc together. This may ultimately prove to be advantageous for Italy as it seeks to mitigate and solve its banking crisis.