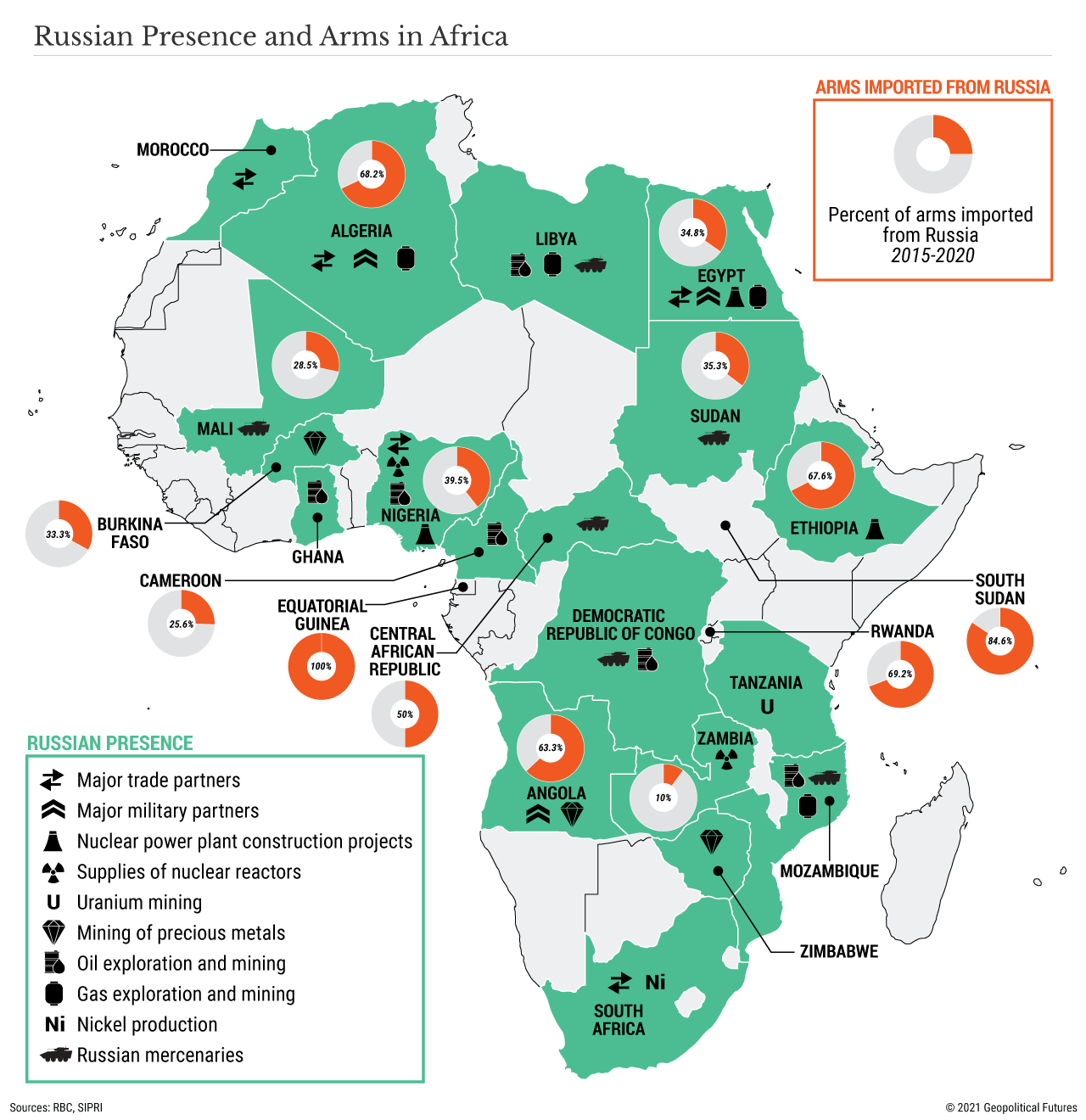

There’s been much talk of late about Russia’s growing presence in Africa, and indeed, it has many military and economic operations throughout the continent. Russian mercenaries are present in several African nations, including Libya and the Central African Republic. Moscow is in talks on strengthening military cooperation with Mozambique and building a new military base in Sudan. And just in the past three months, the Kremlin signed military cooperation agreements with both Nigeria and Ethiopia. However, given the relative size of Russia’s presence here and the fundamental problems it will face if it wants to increase its involvement further, the concerns Western countries have raised over Moscow’s engagement on the continent are overblown. Other outside powers – most notably, the United States, Europe and China – have much bigger footholds on the continent, and there’s little reason to expect that to change anytime soon.

Russian Interests

Russia’s involvement in Africa really began after the Second World War. The Soviet Union became a key ally for many new African states during the Cold War, providing financial and political support as a defender of anti-colonial liberation movements. By the 1960s-70s, the Soviet Union had established diplomatic relations with nearly all the independent states of Africa. It also increased the amount of aid it provided to African states, not only in the form of loans but also investments in the industrial sector. In the mid-1980s, the Soviet Union had contributed to the development of about 300 industrial enterprises, 155 agricultural facilities, and about 100 educational institutions. Major joint projects in sub-Saharan Africa included the Capanda hydroelectric power station in Angola (one of the largest hydroelectric stations on the continent), the largest bauxite mining complex in Guinea, a mining and processing plant in Congo and a cement plant in Mali. The Soviet Union had also built naval bases and logistics facilities in Somalia, Ethiopia, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Angola and Guinea.

The level of engagement declined, however, after the fall of the Soviet Union. Russia withdrew many of its financial and military resources, which were needed to help maintain peace and stability at home. Meanwhile, some of the Soviet-backed regimes on the continent began to collapse as countries underwent political transitions. African states developed deeper ties with the United States, and then China – countries that were willing and able to provide the investments that African nations sorely needed. However, as time passed, Russia became increasingly interested in restoring its global power status, especially after it joined the fray in Syria, another place that has been a focus of global power competition.

For Moscow, then, one of its goals in engaging in Africa is to revive its reputation as a great power. But it also has other geopolitical interests here, and chief among them is gaining access to the Mediterranean Sea. The Kremlin recognizes that having a presence in North Africa would enable it to strengthen its military and economic influence in the Mediterranean and give it access to key trade routes. Russia also views the supply of energy resources to Europe from Africa, particularly Libya, as a threat to its prominence in the European energy market.

Russia especially wants to strengthen its presence in northeast Africa. Here, it sees an opportunity to increase arms exports, a key source of non-energy revenue for the Russian budget, to countries like Egypt and Sudan, which are already major buyers of Russian weapons. In 2020, Sudan signed a deal to build a Russian naval base on the Red Sea – which would give Moscow greater access to the all-important Suez Canal, a chokepoint through which 10 percent of the world’s maritime trade passes – though Sudanese authorities are now trying to renegotiate the terms of the agreement. Having a greater presence in both the Mediterranean and the Red Sea would boost the Kremlin’s leverage over NATO, with which relations have been particularly strained of late.

Meanwhile, the resource-rich western, southern and central areas of Africa are also of interest. West and central Africa have large deposits of cobalt, diamonds and copper, in addition to oil and gas as well as rare earths and precious metals like platinum, palladium, gold and uranium ore. Although Russia has its own substantial reserves of many of these resources, extracting them isn’t easy or cheap. Uranium mining, for example, is much less expensive in Africa, and the cost of oil production in Russia has increased for the fourth year in a row. Meanwhile, Russian deposits of gold, diamonds and uranium are depleting fast.

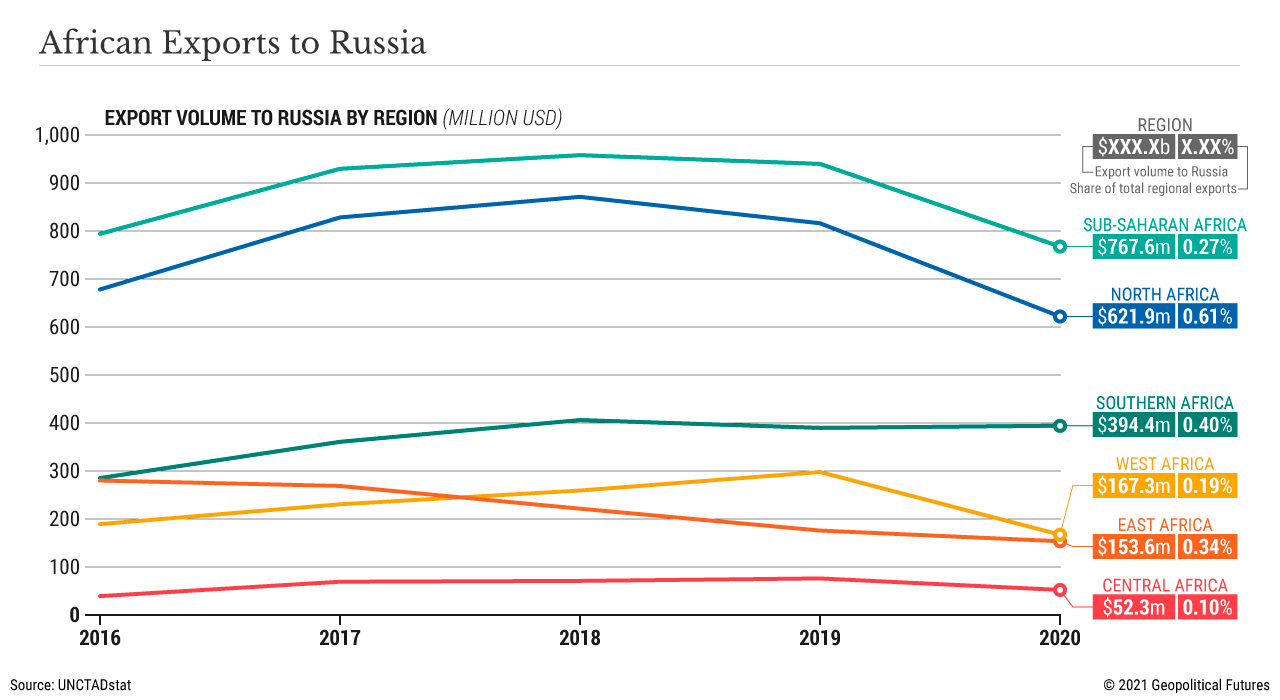

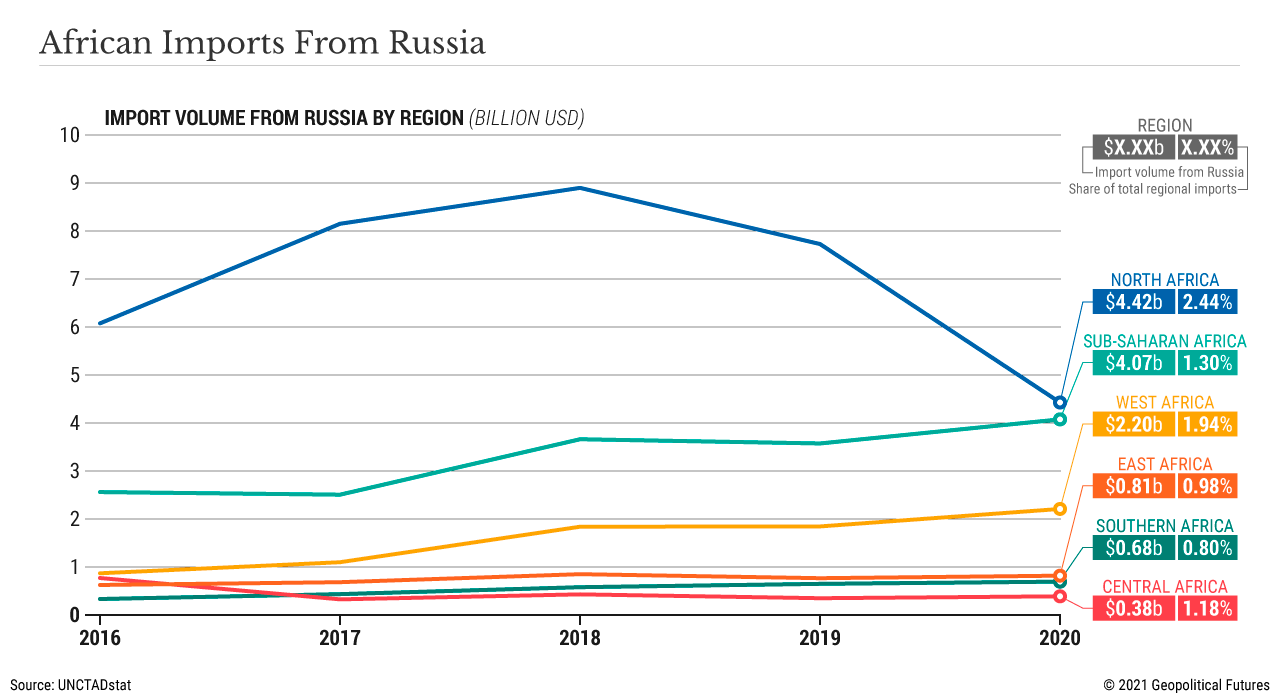

In addition, Africa is a growing destination for Russian goods, especially non-energy exports. While Russia’s list of potential markets is shrinking because of Western sanctions, African countries have remained more or less open to doing business with Moscow. Thus, the continent is an increasingly important market for Russian exports – ranging from agricultural products to more sophisticated goods like military equipment. Even in 2020, during a global pandemic, Russian exports to Africa grew by 7 percent to $2.4 billion – mostly consisting of grain and weapons, with Algeria and Egypt being the largest buyers. Major Russian mining companies like Alrosa, Rusal, NordGold, Uralchem and Renova as well as oil and gas giants Gazprom, Rosneft and Lukoil are all active in Africa.

Russia’s Limits

Russia, however, is far from achieving its goals there. Despite some successes in advanced industries, Russian companies are mainly involved in the low-value-added sector. And the firms that have a presence in Africa are among Russia’s largest and best connected, meaning they can afford to take a risk, knowing their business won’t be hugely affected if their Africa operations take a nosedive. For small and medium-sized businesses, however, African markets remain out of reach. In addition, Russian companies have to compete with larger firms from countries that have long-established ties in the region. What’s more, bilateral trade between Russia and Africa as a share of total trade remains relatively low for both sides – roughly 1 percent (although slightly higher in North Africa). In terms of trade turnover and investment, Russia is a much smaller player than China, the United States, Europe and even newcomers Turkey and India.

Russia’s military presence in Africa is also limited. Though it’s an important arms provider – more than a third of all arms supplies to Africa come from Russia, while only 14 percent come from Moscow’s French competitors – it hasn’t been able to translate this into deeper cooperation that would give the Kremlin influence over decision-making.

The presence of mercenaries from the private Russian security firm the Wagner Group also complicates the situation. According to reports, there are about 2,000 Russian mercenaries training the army in the Central African Republic, 2,000 more operating at the Jufra air base in Libya (plus others at an air base and port in Sirte), and between 160 and 300 in Mozambique. These numbers are too low to make any real impact. Rumor has it that Russia has agreements with some countries to extract gold in exchange for the mercenaries’ training of local troops. So, in addition to military training, the mercenaries are likely guarding Russian mining and business operations in these countries. Thus, it’s a stretch to claim that their presence means Russia has substantial influence here.

In the military sphere, Russia isn’t going to go much further than supplying weapons and providing Wagner’s services, lest it gets entangled in the region’s many ethnic and territorial disputes. In addition to the fact that doing so wouldn’t be in its interest, waging war in such remote and distant locations would be extremely difficult without having bases and logistics in the region.

One of Russia’s biggest obstacles to increasing its influence on the continent is the presence of competitors, particularly Western countries and China, that have been in this market for much longer and may have more capital at their disposal. Russia lacks a systematic approach to developing relations with African countries. Although Africa is a growing focus for Russian officials, Russian diplomacy is much more subtle and limited here than in other regions. Therefore, the reaction of Western observers to Russian activities in Africa gives the impression that Moscow is a far bigger player than it actually is. And this perception – when used as a tool in negotiations – may actually be Russia’s biggest advantage in Africa.

The Road to 2040

The Road to 2040