By Ekaterina Zolotova

The standoff between the West and Russia got more complicated when Washington imposed new sanctions against Moscow. The Europeans were quick to criticize the sanctions. Germany’s foreign minister raised concerns about U.S. intentions, France questioned the sanctions’ legality, and the European Commission president made threats that he later had to walk back. Suddenly, to the Kremlin, the sanctions looked less like a setback and more like an opportunity. If Russia can play the victim, it may be able to drive a wedge between the U.S. and the EU, more sympathetic as Brussels may prove to be.

There’s just one problem: Sanctions are just one way the U.S. is pushing back against Russia.

Russia has long been a major supplier to the European energy market. Put another way, Russia’s economy depends on its sales to Europe’s energy market. So Moscow took notice when recently the U.S. delivered its first shipment of liquefied natural gas to Lithuania, a country that at its nearest point is just more than 400 miles (650 kilometers) from Moscow. In fact, U.S. natural gas shipments have been appearing all over Europe lately in the wake of the American shale gas boom. This is the sort of encroachment that Russia is compelled to respond to. The challenge for Moscow is to do so without appearing threatening to Europe and thus pushing it closer to the United States. One place it might be able to do that is the Caucasus, specifically around Georgia and its breakaway republics, the very place where Russia announced its return to history in 2008.

Breakaway Territories

Russia has always kept a close eye on the Caucasus. This complex region has historically been riven by conflict. The most recent was, of course, a war between Russia and Georgia in 2008 over the breakaway Georgian republics of South Ossetia and Abkhazia.

Russian troops are still stationed in the republics. In fact, South Ossetia’s military was integrated into the Russian military in July as part of a 2015 agreement that provides for the formation of common defense and security between Russia and South Ossetia. The South Ossetian military is small, and its incorporation will not significantly affect the strength of the Russian army. It does, however, attest to Russia’s long-term plan to absorb a united Ossetia. Whether it can is another question, leaving open the possibility that Moscow will have to make do with a restive republic that is militarily if not politically beholden to the Kremlin.

A Russian multiple rocket launcher passes a banner featuring a portrait of then-Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin outside the South Ossetian capital of Tskhinvali in 2008. DMITRY KOSTYUKOV/AFP/Getty Images

A Russian multiple rocket launcher passes a banner featuring a portrait of then-Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin outside the South Ossetian capital of Tskhinvali in 2008. DMITRY KOSTYUKOV/AFP/Getty Images

Russia also plans to strengthen its position in the Caucasus by focusing on energy agreements. It wants to create a vast space for cooperation in Eurasia – with Moscow in the dominant spot, of course. The most important part of this plan for Russia is to establish control over the region’s oil and gas pipelines. Doing so will give Moscow control over energy supplies to Europe even if the supplies are not directly sourced in Russia.

The recently introduced sanctions, as well as the conflict in Ukraine, have delayed Russia’s plans to increase the supply of energy resources to Europe. The Caucasus, through which Europe also receives energy resources, gives Moscow a way to get back on track The Caucasus is poised to become a larger provider of European energy because several countries in Central Asia and the Caucasus (especially Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan) are rich in natural resources, including oil and natural gas. And the EU is eager to diversify its energy supply – relying too much on one supplier puts it at risk of disruption. The European Union currently receives almost 40 percent of its oil supplies from the countries that make up the Commonwealth of Independent States, a Russian-led confederation of states that generally cooperates on economic matters. Russia accounts for 27 percent, while Kazakhstan provides almost 7 percent and Azerbaijan about 4 percent.

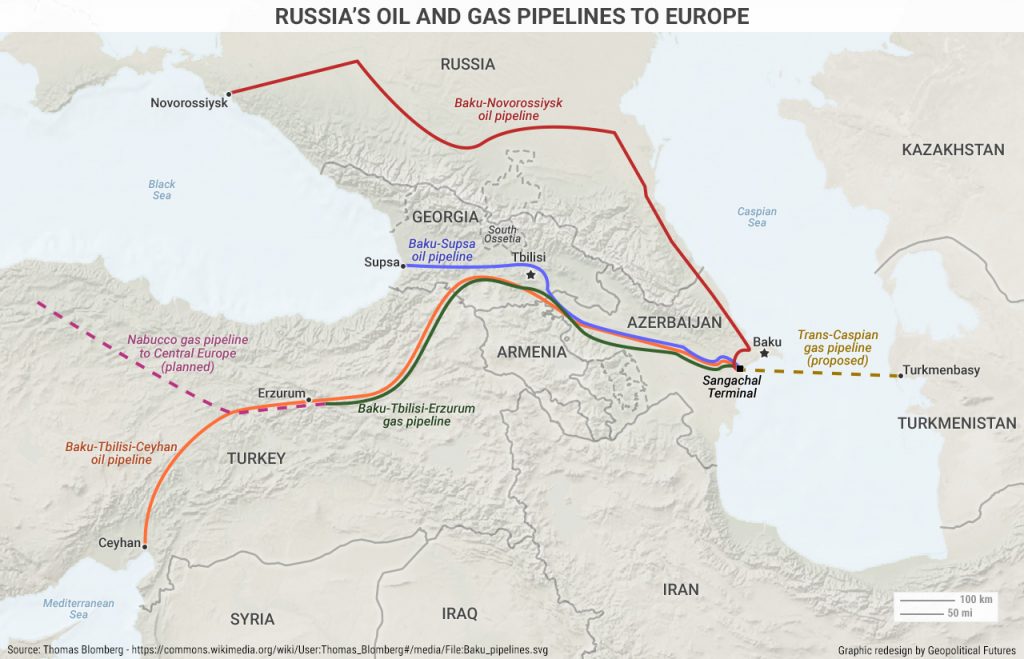

Europe gets oil from this region through the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline and the Baku-Supsa pipeline, and natural gas flows through the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum pipeline. All of these pipelines transit Georgian territory. That’s a source of strength for the Georgian government, but it’s also a vulnerability.

In late July, the Russian armed forces advanced the borders of South Ossetia slightly, putting a small stretch of the Baku-Septa pipeline within South Ossetia’s territory. This gives South Ossetia – or really, Russia – the ability to cut off supplies, or at least siphon off what it wants. Georgia could avoid this stretch of the pipeline, but not without incurring the added cost of loading the natural gas onto trucks or trains and shipping it overland.

Russia’s Reply

Herein lies Russia’s reply to U.S. actions. The U.S. ramped up natural gas deliveries to Europe, so Russia took hold of part of a Georgian pipeline that supplies gas to Europe. The U.S. led seven other countries in Noble Partner 2017, a large-scale military drill in Georgia, so Russia launched its own military drills in the North Caucasus and South Ossetia, which included about 16,000 Russian servicemen. And Russia completed the accession of South Ossetia’s army into Russian forces.

Georgia wants stronger ties with NATO. To strengthen them, it has to distance itself from Russia. But as long as Russia has leverage over the oil and gas passing through Georgian territory, it can’t do that. Georgia was the first country to abandon the post-Soviet identity and try to escape from Russia’s sphere of influence, but it can’t exist isolated from the Caucasus region. This, plus its dependence on energy supplies, obligates Georgia to cooperate with Russia in the energy sector in the Caucasus.

Russia has demonstrated to the U.S. that it can counter U.S. energy imports to Europe and continue to have significant control over the energy flows between the Caspian region and Europe. Recognizing the potential of the Caucasus region, the EU has been participating in the development of its energy sector. So it is important for Russia to maintain and strengthen its influence in the Caucasus. Russia has the ability to influence regional authorities as well as BP, which operates in the South Caucasus. The timing and energy focus of Russia’s pivot to the Caucasus indicate that this is part of Moscow’s response to U.S. sanctions.

It is in Russia’s interest to increase control over the pipelines passing through the territory of Georgia, but every move Russia makes to achieve that goal makes Europe more suspicious of its intentions, thus making it harder to drive a wedge between European countries and the United States.