In recent years, there’s been a periodic and predictable exchange between the United States and the Northern Triangle countries – Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala. A group of immigrants heads north to the U.S. to escape poverty and insecurity, whereupon U.S. policymakers argue either that the immigrants should be stopped in their tracks or that conditions should be improved in their home countries so that they don’t need to migrate in the first place. This rote episode inevitably falls into the background of international affairs, only to resurface a few months later when another “caravan” forms. Occasionally, some security assistance or added consular support would be introduced, but nothing really happens that alters the relationship between the U.S. and the Northern Triangle or that upsets the regional balance of power.

But the status quo is beginning to change, however slowly. Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala certainly continue to call for greater cooperation and funding from Washington, but they are also entertaining overtures from China, a tactic Washington will be unable to ignore.

Obsession

The United States has a long-standing obsession with Central America. Presidents since the mid-1800s have prioritized having a strong U.S. presence there. It’s why the U.S. spearheaded the construction of the Panama Canal and why it paid so much attention to the region during the Cold War. The obsession, of course, stems from Central America’s geostrategic value. The countries form the western flank of the Caribbean basin. They occupy a place where the North American landmass narrows, greatly reducing the distance between the Pacific and Atlantic coasts. (Most of the countries here are bicoastal.) Control and influence over this region and its maritime approach remain critical to U.S. strategy for securing its maritime borders.

Consequently, rivals seeking to unnerve or agitate the United States look to Central America as a point of vulnerability. The Soviets certainly did so during the Cold War, which was a much hotter conflict for the region than the name implies. Indeed, Central America served as a brutal front for fighting between the two global powers. The U.S. kicked things off in 1954 by supporting a coup in Guatemala, though the primary years of action did not occur until the 1980s when domestic political unrest created an opening for the Soviets. What followed was 36 years of civil unrest in Guatemala, 12 years of civil war in El Salvador and the U.S. using Honduras as a staging ground for troops that participated in 12 years of fighting during Nicaragua’s revolution. The details vary by country, but the results were the same: structural economic damages, a poor security atmosphere that rewarded illegal behavior and weak political institutions monopolized by elites.

This is precisely why so many migrants are so eager to flee to the United States, and it’s precisely why China is uniquely able to capitalize. The U.S. and the Northern Triangle broadly understand that investment and aid are necessary to improve socio-economic conditions, but they don’t agree on how much or where it should go, and there are often strings attached. For example, Northern Triangle countries are currently seeking as much as $30 billion in financing, yet Washington’s most recent offer was just $4 billion and was accompanied by calls for political and economic reforms. Washington believes it cannot trust that the funds will be used effectively. (Its concern isn’t entirely misplaced. The U.S. has open court cases against top Guatemalan officials for corruption and top Honduran officials for drug trafficking, and lawmakers are debating how to respond to the El Salvadorian legislature’s vote to replace five supreme court judges and the attorney general. This makes it hard for both sides to engage in good faith.)

A Few Grand Gestures

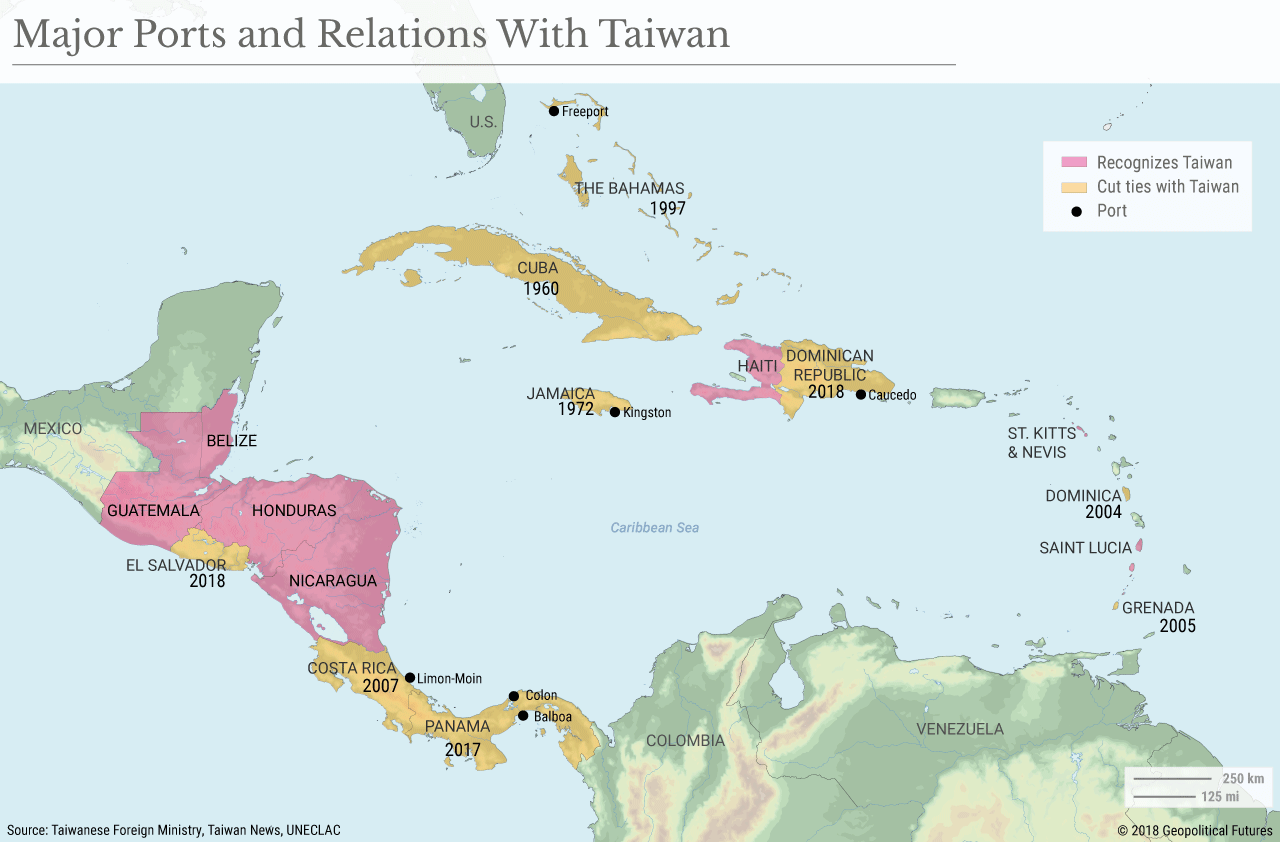

The U.S. has had little reason to change its approach to the Northern Triangle – that is, until China began to court the region more earnestly and vice versa. Washington has been particularly worried about El Salvador. In 2018, the government decided to recognize China over Taiwan, when Beijing expressed an interest in developing La Union port. More recently, when the president removed the supreme court judges, Washington sent an envoy to San Salvador who was ignored by the president. More, a week later, the legislature ratified an agreement with China for the construction of a stadium, library and water treatment facility. Vaccine diplomacy has also been put in play with several shipments of China’s Sinopharm delivered to El Salvador.

Washington has fewer options to manage the situation now than it did during the Cold War, when the specter of communism “justified” all sorts of sordid behavior. (Indeed, over the years, details of U.S. actions and operations in the Americas during the Cold War have come to light and clearly show its role in the violence and instability in the region.) Being too heavy-handed will only alienate the region and likely push it further into China’s sphere of influence. Even using clandestine approaches through civil society groups and nongovernmental organizations is difficult. Previous attempts to leverage aid programs as a solution have been pursued by U.S. presidents from John F. Kennedy to Barack Obama, and all of them failed.

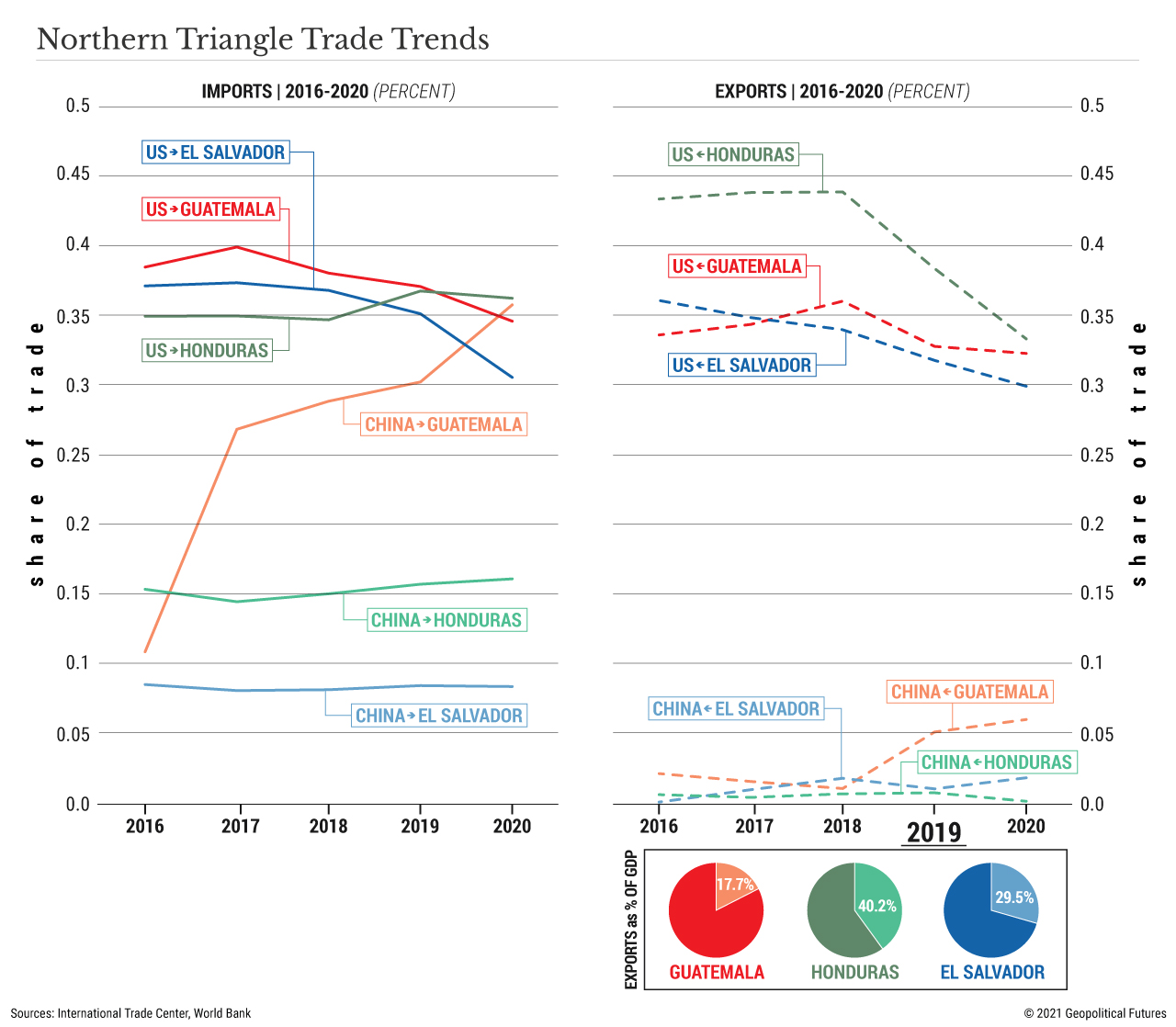

Constraints such as these have led many to propose that the U.S. increase trade, near-shoring and general economic engagement with the Northern Triangle. Crucially, these proposals intersect with the broader U.S.-China trade war. The U.S. already has the upper hand in trade with these countries, all of which have moderate to high dependencies on exports. They’re attractive candidates for near-shoring activities, especially given their close proximity and relatively cheap labor, but security is a strong impediment. Additional financial firepower could also be acquired by leveraging relationships with Taiwan, which values the diplomatic recognition it has received from Guatemala and Honduras.

It’s a bit of a double-edged sword. But putting trade and economic projects at the fore plays directly into the broader U.S.-China trade and economic wars. There’s been lots of hype about increased Chinese presence in Latin America, but the degree and type of influence vary drastically by location. Northern Triangle countries have few natural resources that would be attractive to China. And Beijing’s push for shifting manufacturing production to higher-tech, value-added goods would not find many buyers in the region. Even so, China is a giant market that could offer preferable terms to increase its share of trade, which is relatively small in these countries, and gain space in their economies.

Notably, China has become a bit more judicious with the types of infrastructure projects it invests in. But given the strategic value of these countries to the U.S., the geopolitical gains could well make up for any financial losses. There is, of course, the traditional danger of a country getting caught in a debt trap, but tomorrow’s problems would not be enough to discourage the Northern Triangle from today’s gains. China’s ability to conduct business in legal gray areas is compatible with the patronage systems still employed by Northern Triangle countries, thereby allowing them another source through which to funnel money to support networks. There also exists the longer-term potential threat of China introducing a digital footprint in these countries by helping develop surveillance technology or telecommunications systems.

The U.S. faces a pressing need to consider how it wants to reengage the Northern Triangle in light of this competition. Right now, Washington holds the upper hand on the economic front and is the dominant hemispheric security power. However, China is more than capable of undermining Washington’s position with just a few grand gestures. Beijing’s foothold in the region is small for now, but it’s too strategically valuable not to be at least targeted, especially considering that the U.S. threshold for tolerating risk there is so low.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East