By Antonia Colibasanu

Russia became the world’s top grain exporter in 2016 with a record production of 120 million tons of wheat, according to Russian statistics agency Rosstat. But poor weather conditions have affected this year’s production. Russia’s grain harvesting season normally starts in June, but this year, it started in July. Cold temperatures have delayed crop ripening and have slowed down field work. As a result, total output is expected to be 17 percent lower than was originally anticipated.

This is noteworthy for two reasons. First, grain, wheat in particular, is an important component of Russia’s food supply, and a shortage could lead to social instability. Second, the worsening conditions in the food sector and declining grain exports could have a detrimental effect on the economy.

Russia’s Agricultural “Rebirth”

The Russian agriculture sector experienced a remarkable boom after 2014. When Western countries imposed sanctions on Russia following Moscow’s annexation of Crimea, the Kremlin retaliated by banning food imports from these countries. Russia portrayed this as an opportunity for the sector’s “rebirth” – local businesses no longer had to compete with European producers. This may have been true to an extent, but the Kremlin can’t control the weather, and this year’s crop proves just how vulnerable the sector is.

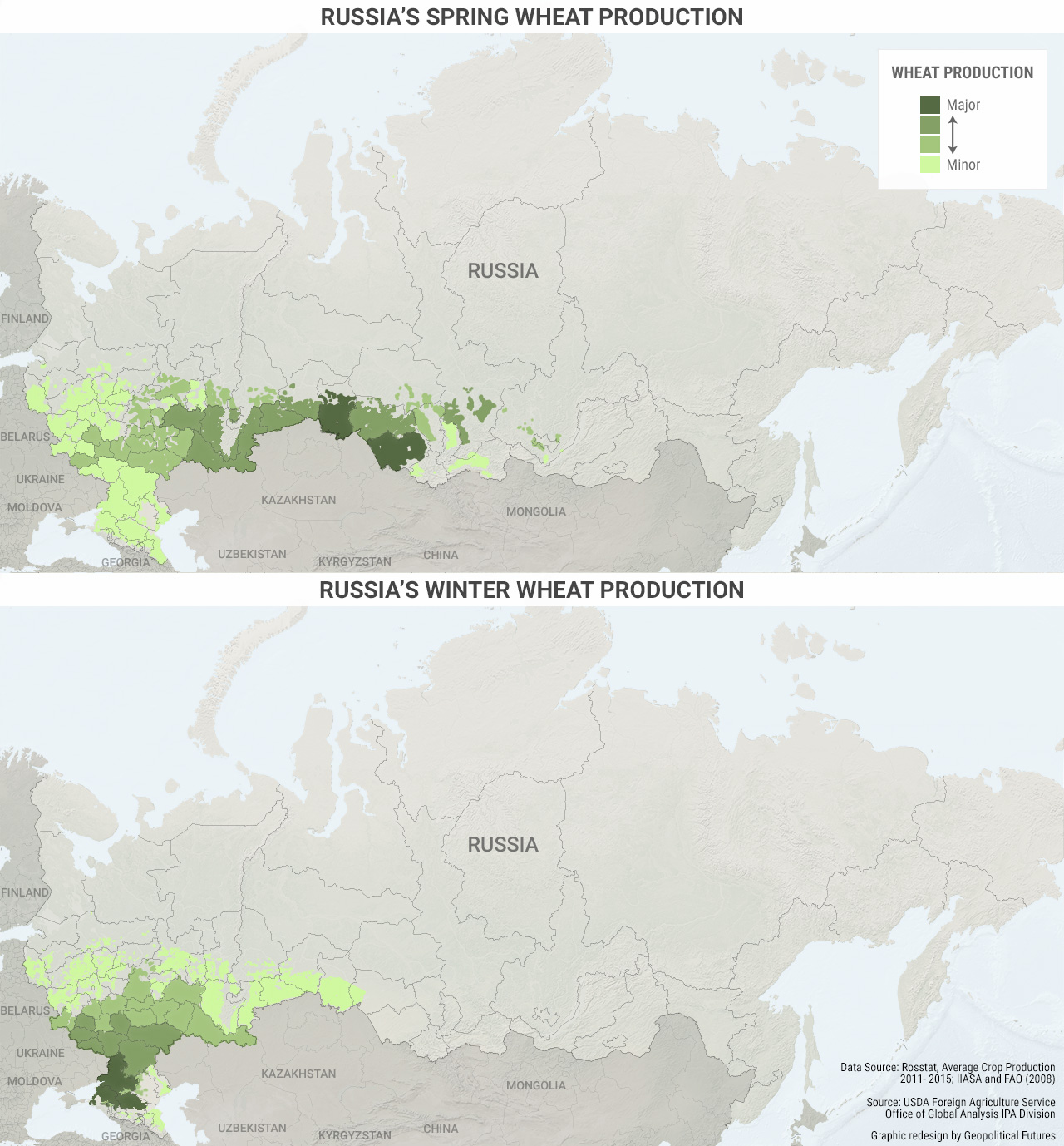

More than half of Russia’s agriculture sector is dedicated to farming, 80 percent of which is grain production. Of this grain production, 60 percent is wheat. Wheat is cultivated on more than 48 percent of Russia’s total area dedicated to grain and oilseed crops. Russia relies on wheat more than any other foodstuff as an important component of its food supply. In fact, roughly 70 percent of wheat produced in Russia annually is consumed domestically. From Siberia to the westernmost regions bordering Europe, wheat is a staple in most parts of the country. Other food products like meat and vegetables are too perishable for the majority of Russians to rely on.

Weather is the most important factor that affects grain production and the agriculture industry as a whole. The government has invested in building storage facilities so that harvested crops can be stored for seasons with poor yields. It has approved a plan to expand its grain storage capacity to 130 million tons by 2030, particularly in an attempt to meet the needs of the eastern part of the country. Russia currently has a total storage capacity of 120 million tons – but most facilities need to be upgraded, and very few can effectively hold grain stocks, according to the Russian Grain Union. Russia’s most important storage facilities are located in the southwest, in the Ural region and close to the border with Kazakhstan. These facilities hold grains for export and domestic consumption, but poor infrastructure linking the facilities to the eastern parts of Russia has left these eastern regions vulnerable.

The state holds roughly 25 million tons of grain on reserve in case of poor harvests. Considering that Russians consume 75 million tons annually, the Kremlin believes a minimum of 50 million tons of grain needs to be harvested to supply the domestic market. When production gets close to this minimum level, as it did in 2010, the government considers introducing drastic measures, including banning exports. This, in turn, affects the global market because Russian exports account for 10.5 percent of the world’s wheat exports.

Increasing Prices

It’s not yet clear how badly the agriculture sector will be affected by this year’s low yields, but the Central Bank of Russia is expecting the rate of food inflation to increase in the third quarter. In fact, food prices have already increased. The minimum cost of a month’s worth of food per person, estimated at 4,233 rubles ($71), has increased since the beginning of the year by 14.9 percent on average in the country and by 16.4 percent in Moscow. As a result, in June, the consumer price index rose by 4.4 percent in annual terms, which is higher than the 4 percent inflation target set by the central bank.

The only thing worse for the Kremlin than high inflation is increasing domestic wheat prices. News of Russia’s declining grain production and the one-month delay of the harvesting season have already resulted in an increase in the export price of wheat, possibly making wheat in Russia more expensive. The current price is closer to levels seen in 2015, when Russia implemented an export duty on wheat as the value of the ruble declined because of falling oil prices.

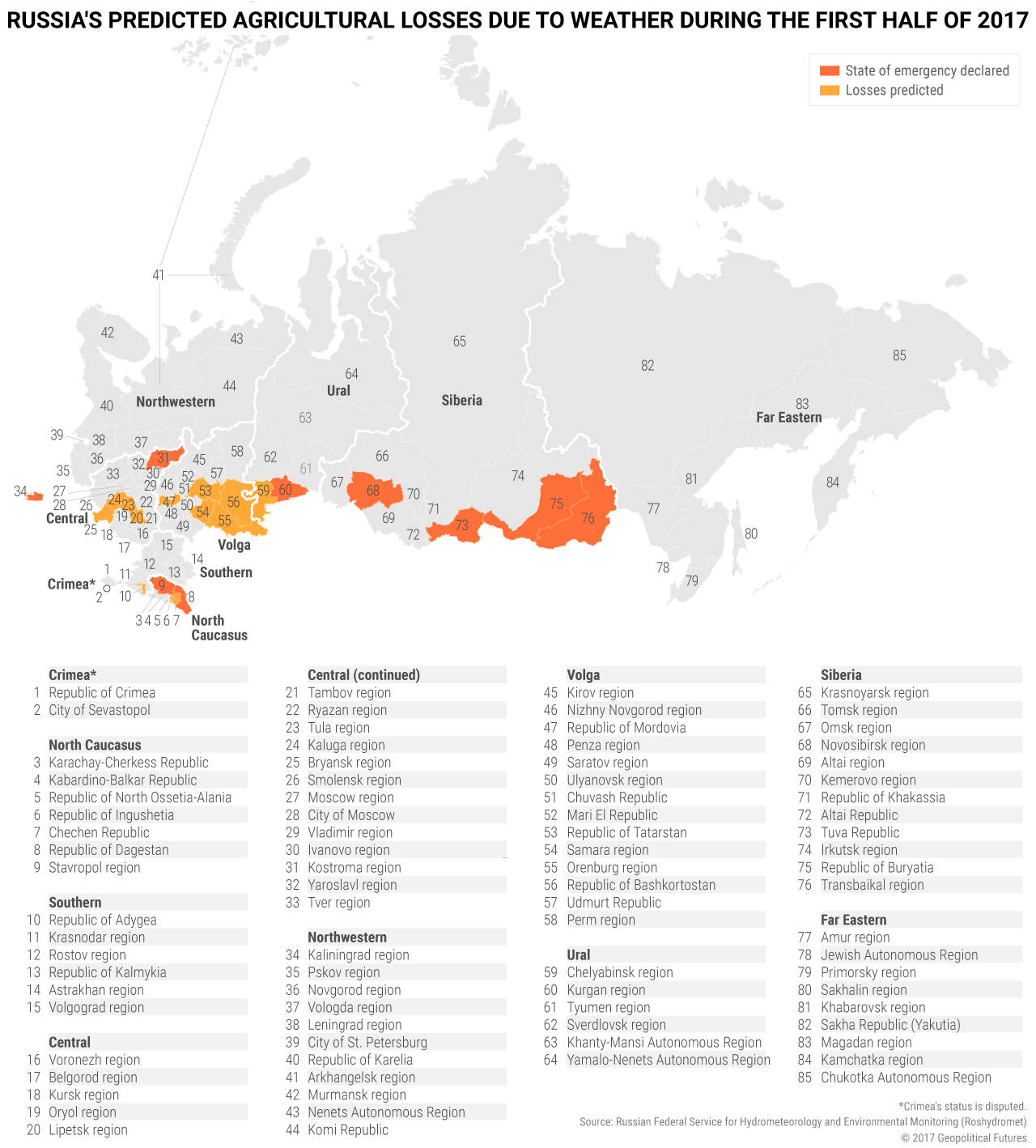

This time, it’s the weather that may drive Moscow to act. Russia’s western regions have experienced a cold spring and summer, with temperatures 3 degrees Celsius (5.4 degrees Fahrenheit) lower than normal for May and June. These two months are important for both winter and spring grain crops. For winter crops, this is the ripening season; for spring crops, it is when seeds are planted. Lower temperatures in the summer affect growth and crop quality. In the next month, temperatures are expected to be lower than average.

Russia’s Federal Service for Hydrometeorology and Environmental Monitoring anticipates that several regions will suffer agriculture losses due to bad weather. Several regions also declared a state of emergency because of severe weather conditions. This covers a large agricultural area, indicating both winter and spring crops may experience problems.

The National Association of Agriculture Insurers estimates that losses caused by adverse weather conditions for winter crops will total 2.6 billion rubles. But the NAAI can cover only up to 1 billion rubles. It’s unlikely that the state will be able to make up the difference, since its budget to cover agriculture losses has been cut to 2.5 billion for the entire year. Since 2011, the state has subsidized 50 percent of the costs of agriculture-related insurance.

Domestic Supplies Are the Priority

Russia is a massive producer of commodities, and though oil is still Russia’s most important export commodity, the country is also a net exporter of grains. Moscow uses commodity exports to gain leverage over other countries. While this has worked well with energy exports, particularly when oil prices were high, it has been less effective with grain exports. Russia’s first priority here is to support its domestic needs, since a shortage in grains could lead to social and political instability.

Since the end of the Cold War, Russia has also tried to maintain influence over grain producing former Soviet states like Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Belarus. This would allow Moscow to control roughly 15 percent of global wheat production in total and almost 17 percent of global exports, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In 2010, when Russia’s wheat production neared its minimum target due to bad weather conditions, it asked its customs union partners Belarus and Kazakhstan to stop exporting grains. Having control over the international price of grain makes controlling the domestic price easier.

In the end, Russia needs to ensure it can meet its own needs and avoid turning to imports because this can have detrimental effects. In the 1980s, the Soviet Union had a massive grain shortage. The U.S. had put an embargo on grain sales to the Soviet Union, which lasted until 1981. While many at the time believed it had only a limited impact, the embargo actually affected average Russians greatly. The U.S. is unlikely to take a similar measure now. But the U.S. and the EU have maintained sanctions against Russia since 2014, so it’s not inconceivable that these sanctions could be extended to grain. While it’s unlikely that Russian production will decline to the point that the country will need to import grains, weather is unpredictable, and Moscow must plan for the worst-case scenario. And even under the current circumstances, Moscow doesn’t have much room to maneuver. Any decline in grain production below expectations could have a negative economic impact – especially at a time when the government is already facing declining revenue.