Originally produced on April 2, 2018 for Mauldin Economics, LLC

By George Friedman and Antonia Colibasanu

The relationship between Poland and Ukraine has a complicated history. From the 1990s until 2015, relations between the two countries were generally positive. Poland backed Ukraine’s bid to join the European Union and supported Kiev through the crisis that broke out in 2014. Poland wants to limit Russian influence in Eastern Europe, and this requires ensuring that Kiev doesn’t drift back into Moscow’s orbit. But since 2015, tensions between them appear to have been rising. The rift stems from the countries’ different interpretations of their shared history.

A Heated Dispute

In 2014, Ukraine’s Russian-backed president, Viktor Yanukovych, was ousted from power after refusing to sign an association agreement with the EU. Since then, two parts of Ukraine’s history have been brought to the forefront in Ukrainian politics, and both have been used as symbols of Ukrainian resistance and its fight for independence. The first is the Holodomor, a famine imposed by the Soviet regime in the early 1930s that killed millions of Ukrainians and was intended to eliminate Ukraine’s independence movement. The second is the paramilitary Ukrainian Insurgent Army, or UPA, and Stepan Bandera, the leader of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. Both groups were involved in the massacre of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia, two regions that were at the time split between Poland and western Ukraine, during the Nazi occupation of Poland.

Following the end of World War II, much of Volhynia and Eastern Galicia became part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, and Poland became a Soviet satellite state. Since both entities were essentially administered, to different degrees, by Moscow, there was a desire to downplay the differences between Poles and Ukrainians and censor any discussion of the killing of Poles at Volhynia and Eastern Galicia and other similar events. Only since Ukrainians began celebrating Bandera as a national hero did these atrocities become the center of a heated dispute between the two countries.

In Poland, the events became the focus of books, movies, and political debates, and in 2016, the Polish parliament unanimously approved a law that declared the massacre at Volhynia to be a genocide. In February, Warsaw went a step further and passed a law making it a crime to deny that the UPA committed crimes against Poles between 1925 and 1950. The Ukrainian parliament then passed a resolution condemning the law.

Nationalist Protests

The revival of these historical events should be seen in the broader context of rising nationalism in both countries. In Poland, nationalist protests have, in part, been a response to policies imposed by the EU and its de facto leader, Germany. The EU’s demand that members accept quotas to resettle refugees following the massive influx of migrants to Europe has angered many and led to calls in Poland for the country to chart its own path. In 2015, the Law and Justice party, which campaigned on a nationalist platform, came to power. Nationalist parties such as the National Movement and groups such as the All-Polish Youth and the National Radical Camp have become more active and are even backed by some supporters of the Law and Justice party.

In Ukraine, a number of nationalist groups emerged, including the Svoboda party, the National Corps, the Right Sector, and the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. Since the revolution, Ukrainian nationalism has served an important purpose: It has been used to fight Russian aggression in the eastern parts of the country and limit Russian influence in the western regions and in Kiev. Ukraine is still struggling to defend its independence, and it faces serious challenges in doing so, both internally and externally. Its history is a critical part of this process.

The biggest nationalist protests in both countries were held last fall, when tens of thousands demonstrated in Kiev and Warsaw. In Kiev, demonstrators marked the 75th anniversary of the UPA by chanting the group’s slogans. In Warsaw, some protesters marked the country’s independence day by holding banners depicting a falanga, a far-right symbol from the 1930s, and shouting slogans that reference the country’s Catholic roots. The march was organized by the All-Polish Youth and the National Radical Camp, a revival of a nationalist 1930s group.

In February, Polish demonstrators gathered in front of Ukraine’s Embassy in Warsaw to demand that Ukraine limit its support for UPA figures. In March, Ukrainians gathered in front of the Polish Embassy in Kiev to protest the Polish law that criminalized the denial of crimes committed against Poles nearly a century ago. Several monuments for the Polish victims of Ukrainian atrocities were also vandalized last year, and a Polish memorial cemetery in Lviv, western Ukraine, was desecrated.

The protests have been accompanied by a diplomatic tit for tat. In April 2017, Kiev banned the exhumation of Poles killed during World War II, and later that year, Warsaw refused to allow the head of Ukraine’s commemoration commission into Poland in response. In December, the Polish president threatened to delay a visit to Kiev due to what the president’s chief aide called an increasingly “negative evolution of Ukraine’s policy in history and national identity with regard to Poland, as well as its deteriorating relations with neighbors from Central Europe.”

Migration

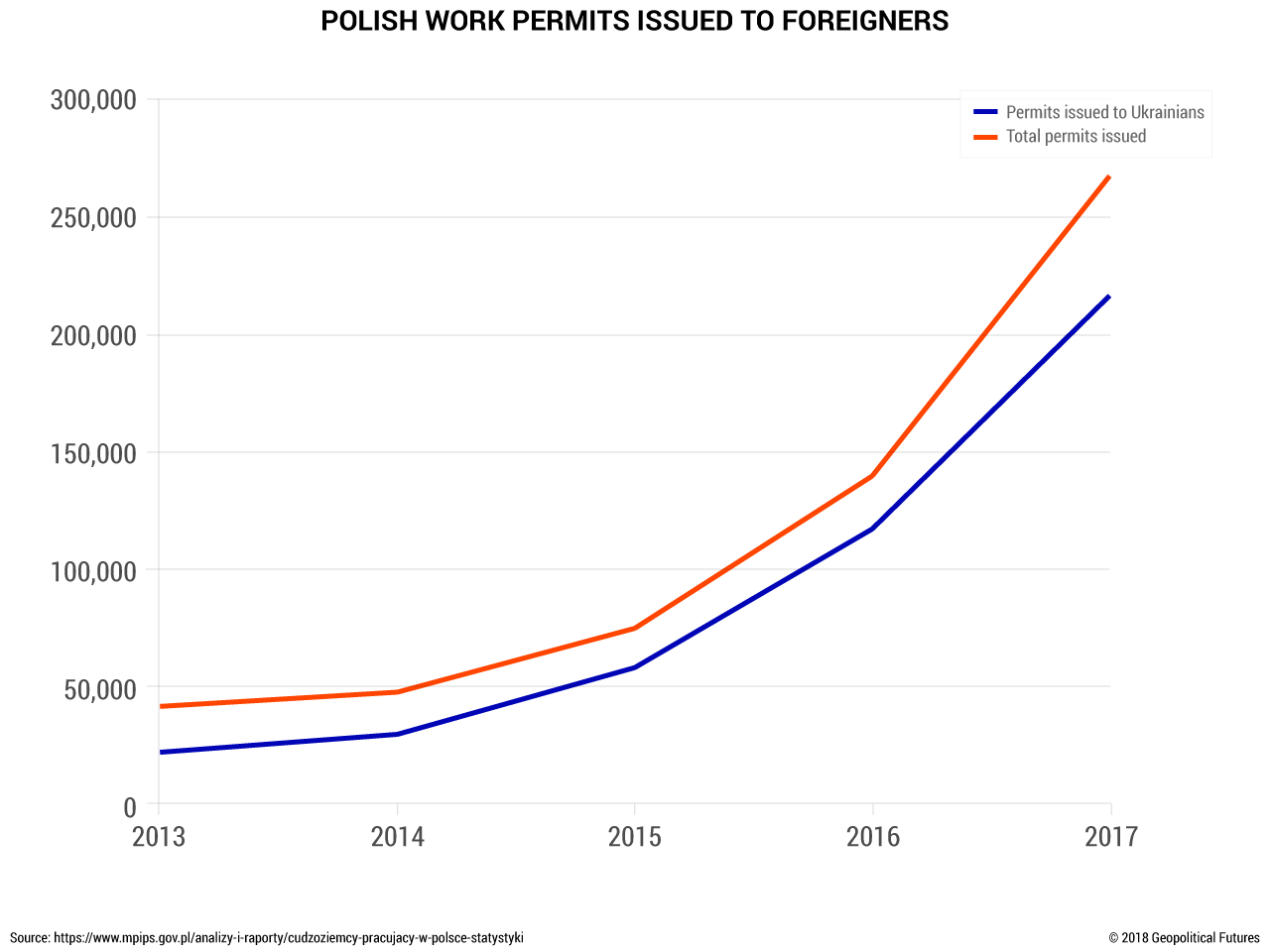

Another factor complicating this issue is the migration of Ukrainians into Poland and the socio-economic implications for Poles. Ukrainian migration into Poland has been increasing since 2014 and is the largest migration wave in Poland’s contemporary history, according to national statistics. Though this is a positive development for Poland’s rapidly growing economy, it also comes at a cost.

According to a report published by Polish human resources company Work Service in December 2017, about 2 million Ukrainians were working in Poland at the end of 2017, an increase from only 1 million in 2016. This number is expected to rise to 3 million in 2018. Ukrainian citizens mostly fill jobs that aren’t being filled by Polish citizens and are generally paid less than Polish workers, although their wages increased by 20–30% in 2017 compared to 2016. But some Poles fear that as more Ukrainians immigrate to and settle down in Poland, fewer jobs will be available for Poles. This has fueled the nationalist movement against immigration, even though, according to statistics, Poland still needs more workers to support its growing economy.

Ultimately, the current tensions won’t change the fact that Poland needs Ukraine as an ally. In fact, cooperation between the two on military matters increased in 2017, and their economic ties, including trade and investment, have remained consistent. The tensions are indicators of the domestic pressures facing the two governments rather than changes in policy or strategy. Both governments ran on nationalist platforms, and when developments in another country sparked nationalist protests and upheaval among their electorates, they needed to respond. We can therefore expect Ukrainian politicians to continue to invoke the UPA and Stepan Bandera as symbols of national pride and Polish politicians to express their outrage. But not much more will result.

In geopolitics, we focus on the bigger picture, and political rhetoric is rarely significant. There is only one situation in which rhetoric could be consequential: when it touches on matters of national pride and how a nation defines itself. That’s what made the rhetoric in this case so heated and potentially impactful. But it is likely that both countries can contain the rise of nationalism to the point that it will not affect ties between them in any real way, despite more acts of vandalism and protests that are likely to come. Both governments will promise to take a tough stance on the issue while working together to enhance military ties and ensure Russia can’t spread its influence even farther westward.

The Geopolitics of the American President

The Geopolitics of the American President