Originally produced on April 10, 2017 for Mauldin Economics, LLC

By George Friedman and Cheyenne Ligon

The flow of international trade has always been subject to geopolitical risk and conflicts. At all stages of the supply chain, trade inherently faces challenges posed by the geopolitical realities along a given route.

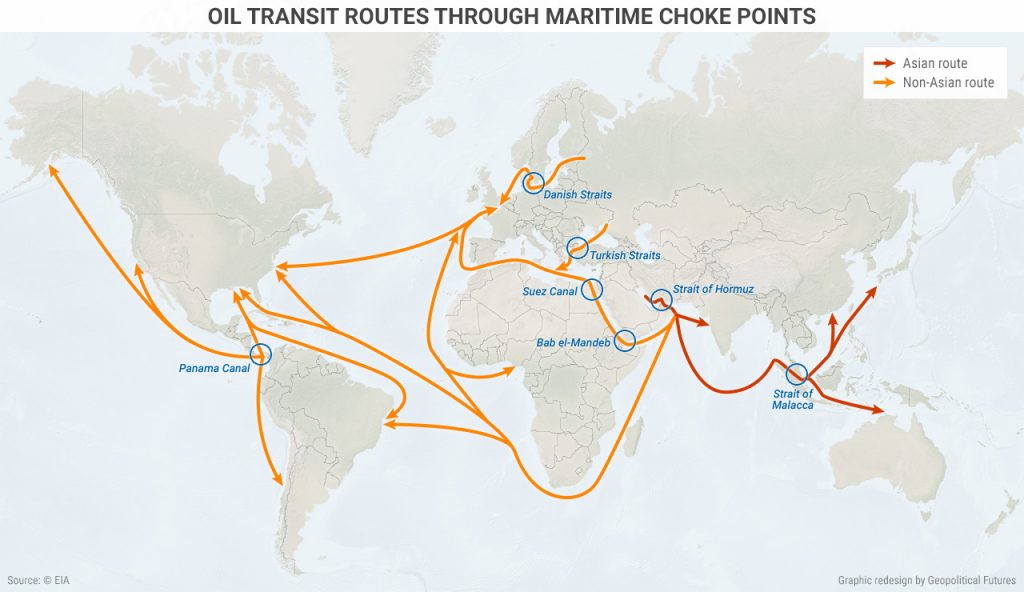

Some routes are more perilous and harder to navigate than others. One such trade route is the maritime path for delivering oil from Persian Gulf producers to East Asian consumers. It faces two critical choke points that are unavoidable given geographic constraints.

The Persian Gulf is a leading oil-producing region, accounting for 30% of global supply. Meanwhile, East Asia is a major oil-consuming region and accounts for 85% of the Persian Gulf’s exports, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA). The most common route for oil deliveries between these two regions is through the Strait of Hormuz, into the Indian Ocean, and through the Strait of Malacca.

The two straits are geopolitical choke points because geographic limitations and political competition threaten access to these routes.

Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz is the primary maritime route through which Persian Gulf exporters—namely Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—ship their oil to external markets. Only Iran and Saudi Arabia have alternative access routes to maritime shipping lanes. The strait is 21 miles wide at its narrowest point, bordered by Iran and Oman. The EIA estimates that approximately 17 million barrels of oil per day—about 35% of all seaborne oil exports—pass through the strait. This path is also the most efficient and cost-effective route through which these producers can transport their oil to consumers in East Asia.

Persian Gulf countries depend heavily on revenue from these exports. For this reason, passage through the Strait of Hormuz is both an economic and a security issue for countries in the region. Disruptions in the strait would impede the timely shipment of oil: Exporters risk losing significant revenue and importers could face supply shortages and higher costs. The longer the disruption lasts, the greater the losses.

Disruptions could take place when Sunni and Shiite countries threaten to deny each other passage through the strait. Blocking access is a way to inflict financial damages on countries that depend on exporting goods through this area. Shiite-majority Iran has threatened to close the strait and plant naval mines to assert its power over Saudi Arabia and other Sunni states. Saudi Arabia and its allies have conducted naval drills to demonstrate their willingness and ability to retaliate should Iran follow through.

Given their financial dependence on oil revenue, Persian Gulf countries have tried to mitigate the risk associated with passing precious exports through the strait in two ways. First, they have established alternative export routes. Saudi Arabia built a pipeline that carries oil from fields in the east to refineries in the west. From there, it is shipped out through the Red Sea. Similarly, the United Arab Emirates built the Abu Dhabi Crude Oil Pipeline to bypass the Strait of Hormuz and export directly from Fujairah Port. In both cases, the pipeline capacity is not enough to relieve dependence on the Strait of Hormuz.

Second, Persian Gulf countries have built security alliances with countries that have a vested interest in keeping the strait open. These security alliances often involve a partnership with the United States. In 2016, the US received 18% of its oil imports from the Persian Gulf. Therefore, it wants to maintain safe passage of exports through the strait. The US also has the most powerful naval fleet in the world. These forces can be rapidly deployed to deter a potential blockage of the strait, since other navies in the area could not compete directly with the US Navy in a confrontation.

Strait of Malacca

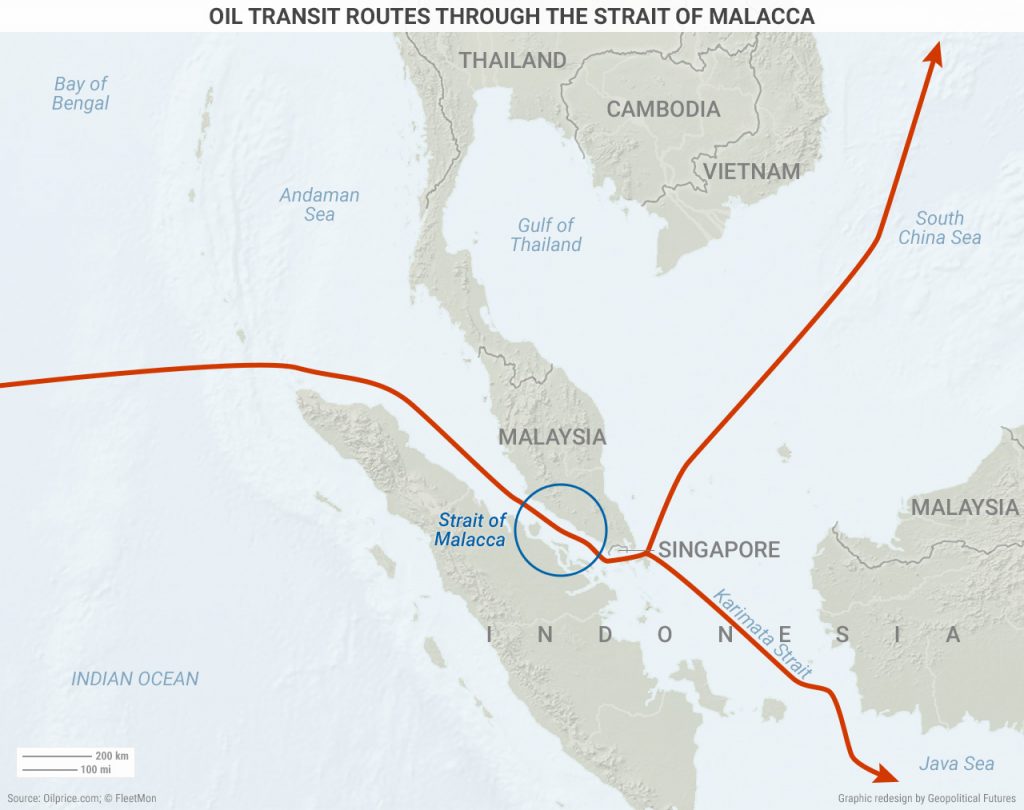

The Strait of Malacca is the shortest sea route to move goods from the Persian Gulf to Asian markets. It is over one-third shorter than the closest alternative sea-based route. This added distance would make the oil more expensive for consumers. Roughly a quarter of all oil transported by sea (more than 15 million barrels per day) passes through the Strait of Malacca, making it second only to the Strait of Hormuz in oil transport by volume.

The Strait of Malacca is 550 miles long and runs past Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. At its narrowest point, the strait is a mere 1.5 miles wide. Its narrowness makes ships more susceptible to piracy (which is prevalent in the area) and blockades.

Both Japan and China’s national economies rely heavily on oil imports that pass through the Strait of Malacca. Therefore, open access through the strait is key to their economic security. Over 80% of China’s oil imports (by sea) and around 60% of Japan’s total oil imports currently pass through the strait. These two countries have a long history of animosity and war as they competed with one another to be the dominant geopolitical power in the region.

However, attempting to block the strait would be a double-edged sword for these regional powers. On one hand, restricting trade flow through the strait could be a way of inflicting economic pain on a rival. This could lead to an economic downturn and subsequent domestic political problems for the rival. On the other hand, initiating a blockade could set a precedent for other countries to vie for control of the strait. This could put either country’s access at risk.

To secure their economic stability, Japan and China have pursued means to guarantee safe passage of oil through the strait. Like Persian Gulf countries, Japan relies on its alliance with the United States to guarantee free navigation of goods by sea. The US Pacific Coast conducts a significant amount of trade with East Asia, and Washington relies heavily on its alliance with Tokyo to offset China’s power and any other potential threats in the region.

China’s strategy involves strengthening its military and political ties in the region. Beijing has forged strong political and economic relations with the countries that surround the Strait of Malacca, particularly Indonesia. It is also in the process of building a large navy with the goal of gaining more control of its surrounding seas.

Conclusion

For both Persian Gulf exporters and East Asian consumers, the free passage of oil shipments is essential. However, these shipments must pass through two geopolitical choke points. In the Strait of Hormuz, the main risk derives from the conflict between Sunni and Shiite powers in the region. In the Strait of Malacca, it is the regional rivalry between China and Japan.

All of these countries must take measures to mitigate their risk and secure free passage through the respective straits as the effects of a blockade would be devastating to local economies. Geopolitics not only explains why such measures are necessary, but also which measures are most suitable for the countries involved.