By Antonia Colibasanu

French President Emmanuel Macron will meet with the leaders of Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Romania and Bulgaria on Aug. 23-25. To the local media, his visit is a sign that he has taken the lead in reforming the European Union, making it stronger and more unified. In truth, he has set his sights on improving his political standing at home and tackling cheap labor from Eastern Europe – and he has a paradoxical way of going about it.

Macron’s Calculation

During his presidential campaign, Macron argued that one of the causes of Brexit was the growing discontent among the British middle class with Eastern Europeans’ “social dumping” in the United Kingdom. Immigrants from the east poured into the U.K. in recent years, taking jobs for less pay than Britons would accept. Macron argued that this is a flaw in the EU: that labor markets are not adequately regulated to ensure that everyone in Europe is paid a similar wage for similar work.

For the French president, the matter hits close to home. In France, the unemployment rate is high – 9.6 percent in the first quarter of 2017 – but the country still attracts temporary workers from other EU countries who will work for less than French workers in construction and similar industries. Most of the temporary workers in France come from Poland (16.9 percent), Portugal (16.1 percent), Spain (15.7 percent), Belgium (13.2 percent) and Germany (11.8 percent). The trend has sparked a nationalist backlash from French citizens who see the cheaper labor coming from other countries as a cause for the high unemployment rate. Eastern Europeans are often the object of their resentment.

Macron’s calculation is therefore simple: Reduce or eliminate the competition from cheap labor, and French employment will increase. To do that, he argues, the EU should set rules to establish universal salary levels. Macron supports changing Directive 96/71/EC, the Posted Workers Directive, which regulates the salaries and permitted length of stay for posted workers – employees who are sent by their employers, on a temporary basis, to carry out a service in another EU member state. (France also lobbied for reducing the duration a worker can be posted from two years to one.)

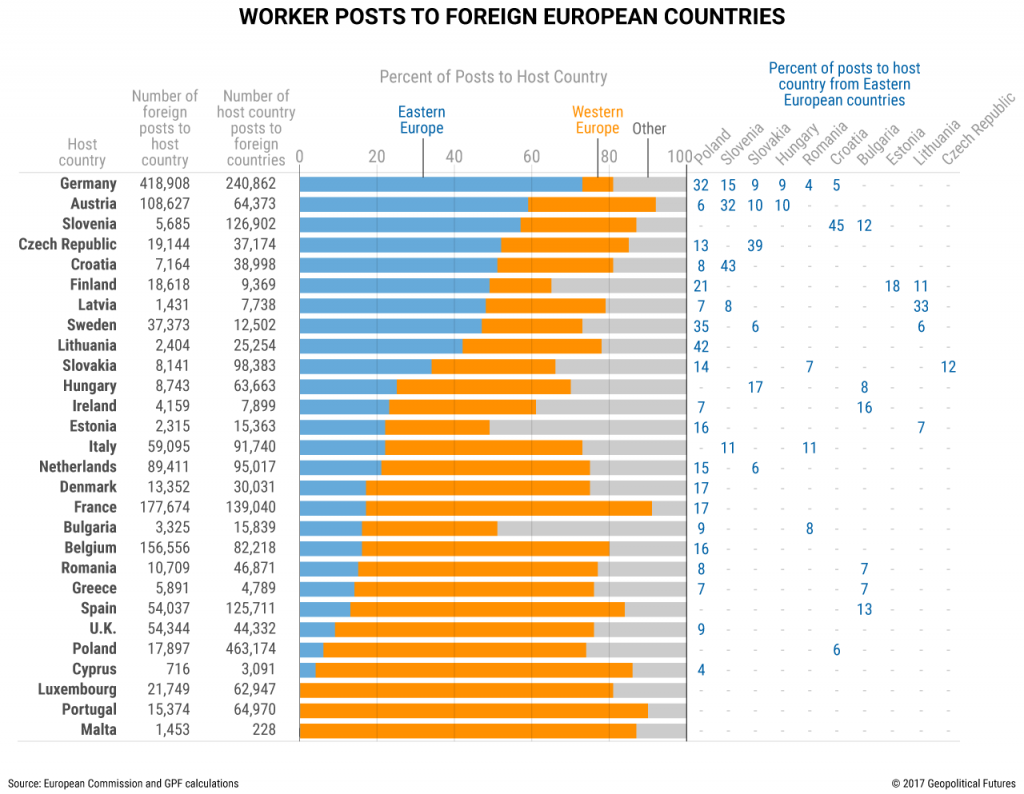

He isn’t alone. Last year, the governments of Germany, Austria, Belgium, the Netherlands and Sweden joined France in sending a letter to the European Commission asking to update the directive so that it respects the principle of “equal pay for equal work in the same place.” Austria and Germany are also major destinations for posted workers from Eastern Europe. Austria, which gets 58 percent of its posted workers from neighboring Eastern European countries, is a staunch supporter of changing the EU directive. It’s unemployment rate has grown as quickly as its nationalism. It’s no coincidence that Macron began his trip there.

At home, Macron has launched a series of discussions among the government, the business community and the labor unions with the purpose of reforming the French labor code and creating a more flexible labor market, which Paris hopes will raise employment levels. The government will present the results of the first round of talks this week. Macron has promised that these discussions will not only shape French labor laws, but they will also become the foundation for the new EU “social model.”

But in reality, France can do little to protect its labor market from cheap foreign labor. The solution can come only from a change of the EU directive for posted workers. And it’s here that Macron has taken an unusual approach: He argues that Brussels should take responsibility for setting salary levels. Ceding more power to the EU isn’t exactly what French nationalists have in mind when they call for Paris to do more to protect their interests.

Options for Reform

For Eastern European companies, cheap labor is a competitive advantage against Western rivals. To date, EU regulations allow posted workers to be paid in line with the wages of their home country, not those of the country they are posted to. The labor market in the east is more flexible than in the west, and because of the lower standard of living, labor costs for Eastern European companies have been significantly lower than in Western Europe. This has attracted foreign investment to Eastern Europe and enabled the east’s companies to increase efficiency by sending workers west.

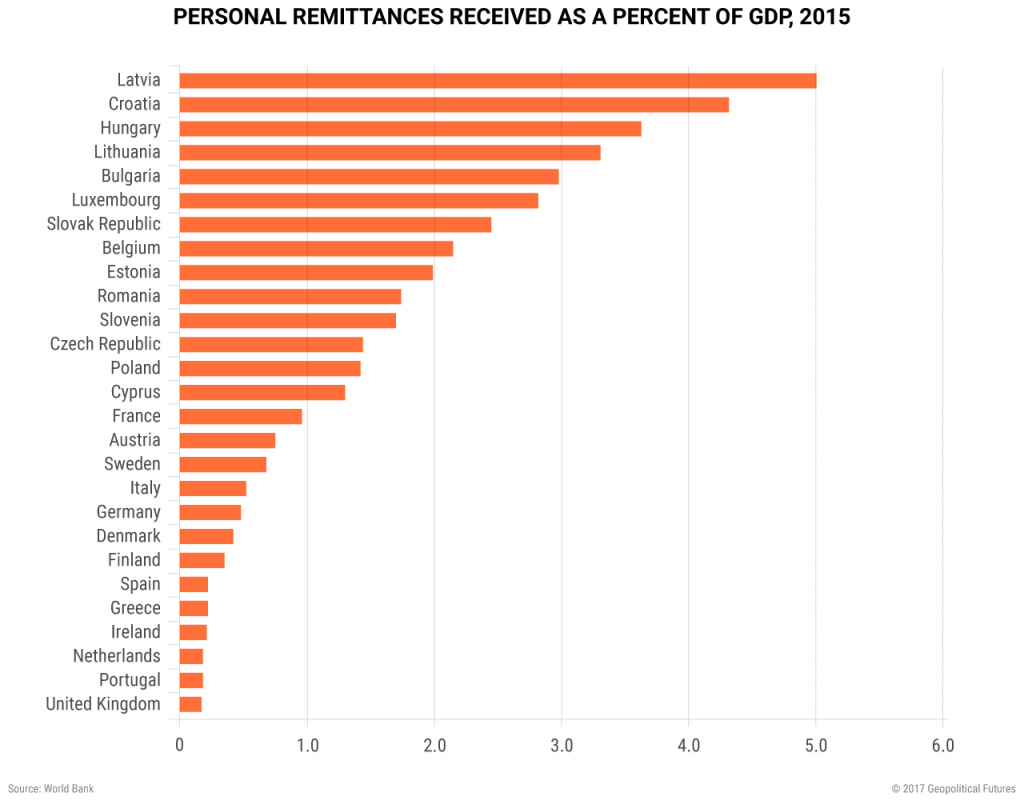

Moreover, remittances from posted workers help fuel Eastern Europe’s economic growth. Poland is the largest source of posted workers in Europe, each year sending more than 460,000 workers to other states, mostly in Western Europe. About 3 percent of all employed Poles are working abroad, and their remittances constitute 1.4 percent of Poland’s gross domestic product. Latvia has only 1,400 workers posted around the EU, but their remittances contribute as much as 4.6 percent to Latvia’s gross domestic product. By comparison, Germany, the second-largest source of posted workers in Europe, sends only 240,000 employees to work in other countries in the EU, and their remittances make up only 0.4 percent of Germany’s GDP. It’s not hard to see, then, why Eastern European countries oppose changes to the directive on posted workers.

The European Council has agreed on the need to change the rules on compensation. The change would leave it to the host government – not the country sending the workers – to establish the salary level for workers sent abroad. But before the change can be implemented, it must be approved by the European Commission and the European Parliament.

This is where things get messy. If the European Commission rejects the amendments, the European Council could still pass them with a unanimous vote. For the reasons outlined above, however, unanimity is unattainable. But if the European Parliament modifies the text and passes it back to the European Council, the council could approve the final text with a majority rather than with unanimity, and the European Commission’s opinion would not be legally binding.

This is the path of least resistance and the one Macron hopes to take. France wants a resolution on the salary levels and length of time posted workers can work abroad, and it wants these to be set by the European Commission rather than by EU member states. If the limits are not uniform, it will create a situation where Western European countries constantly adjust their rules to compete for the best posted workers.

Eastern European governments don’t want to see the rules changed, but if change is inevitable, the European Council’s proposal has their support. As long as individual member states set their own rules, Eastern European governments can defend themselves against Western European protectionism by negotiating bilaterally with the host countries on the terms for their workers. The Eastern European countries will not, however, accept a solution in which Brussels sets the price for their labor market. A supranational institution – even one like the European Union, which benefits from the best technocracy there is – can’t possibly calculate the evolutions of labor demand and supply in every sector.

French President Emmanuel Macron waits for Portugal’s prime minister at the Elysee Palace in Paris on July 28, 2017. BERTRAND GUAY/AFP/Getty Images

French President Emmanuel Macron waits for Portugal’s prime minister at the Elysee Palace in Paris on July 28, 2017. BERTRAND GUAY/AFP/Getty Images

Keeping Up Appearances

But Macron needs to appear to be doing everything he can to lobby for the French interest. This is why he is touring the eastern states, discussing the matter with their leaders and governing parties, seeking to convince them to back some of France’s proposals so that the text of the revised directive will go back to the European Council. He isn’t bothering to visit Poland and Hungary, countries where right-wing parties are in charge that have already publicly opposed his proposals.

Another element of Macron’s tour of Eastern Europe is that it allows him to demonstrate his support for French companies established in the region. Romania, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Bulgaria host more than 72 percent of the French companies with a presence in the region. Romania alone hosts 2,280 entities founded with French capital.

Focusing too much on Macron’s stance on the EU directive for posted workers would be misleading. French nationalism is gaining steam – partly because of the country’s economic problems but also in part because of the perception of a powerful EU whose polices are detrimental to France – and Macron’s solution seems to be to grant the EU more authority to dictate economic policies to sovereign nations. Macron is young, but he’s also savvy. He knows he doesn’t stand a chance of convincing the Eastern Europeans to give more power to the European Commission – he can’t even convince his own people.

But he needs to give the appearance that he’s pressing for change and reform. This allows him to do two things. First, it highlights that Western Europe can’t keep behaving as though it’s on equal footing with Eastern Europe when it comes to the labor market. The western states need more protectionism, and they will implement it. Second, by lobbying to give more power to the EU, Macron is in fact weakening the bloc’s stance because he can put more blame on Brussels for the divergence between Western and Eastern Europe. Macron is heralded as a great reformer – and he’s certainly carrying the flag of one – but his focus right now is on shoring up his position at home.