The North and South have fundamentally diametric economic and political systems and national ideologies. They also have very large guns pointed at each other’s head. Neither side has much reason to trust the other to refrain from trying to exploit the chaos that would come with a transition and force reunification on their own terms. This trust gap is not going away, nor is the prisoner’s dilemma. True reunification would require breathtaking courage from leaders on both sides, who would need to ignore immediate incentives and assume enormous risk while going through the process.

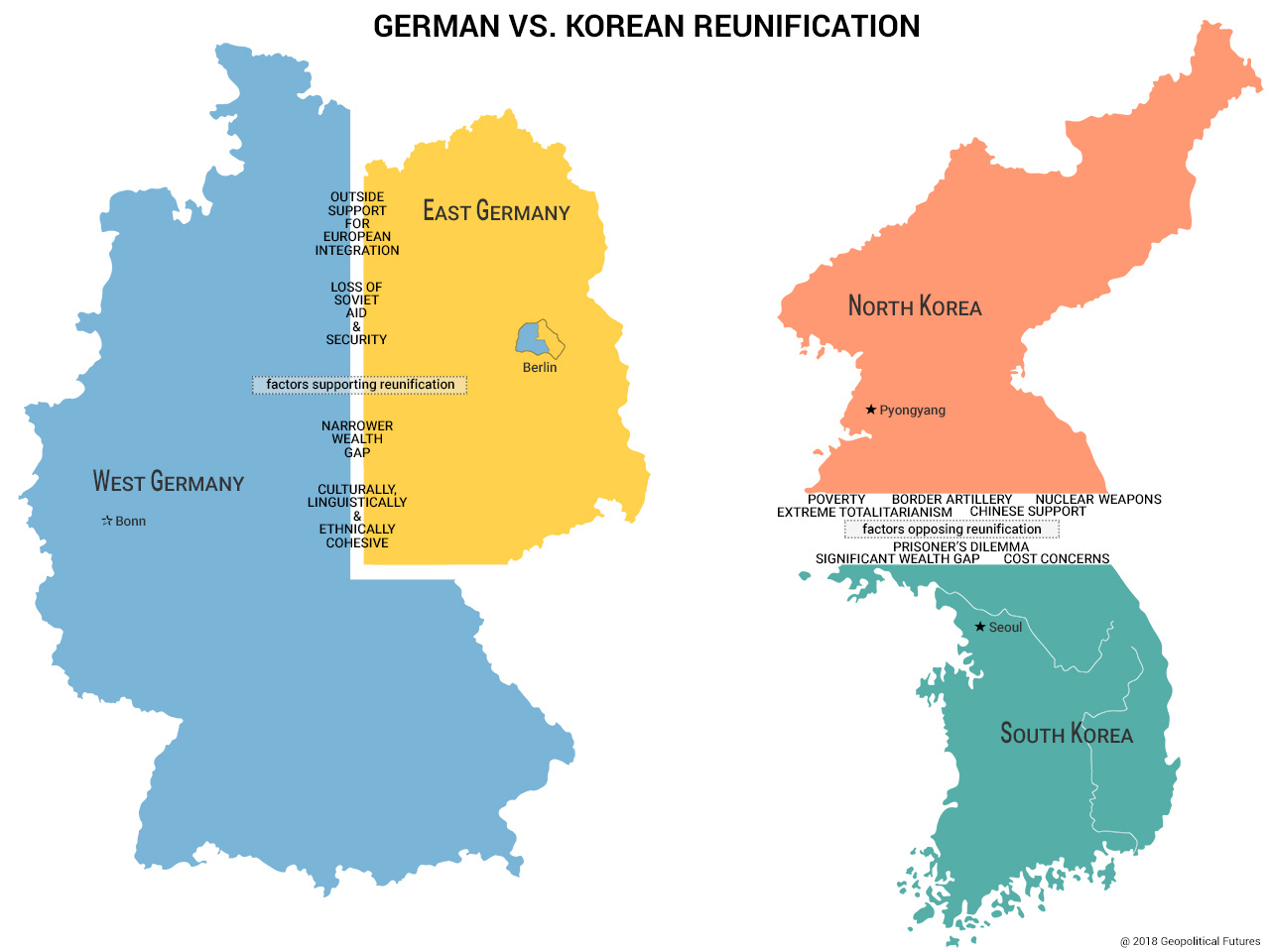

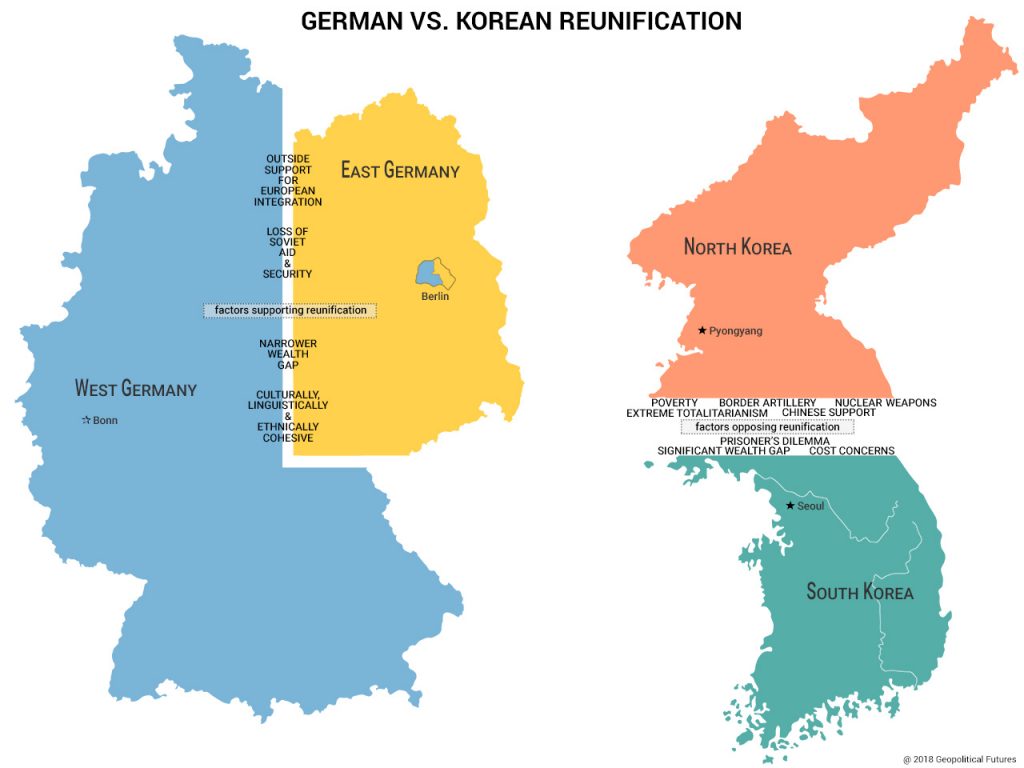

This is, in part, why only two modern states have achieved negotiated, peaceful reunification. One was Yemen in 1990, and its experience ever since has been nothing anyone wants to replicate. The more instructive comparison is Germany, which reunified the same year. Prior to being sliced in two by outside powers, both Germany and Korea were cohesive cultural, linguistic and ethnic entities. Yet both became locked in a protracted zero-sum contest for supremacy between their competing halves. Both are surrounded by countries that, through the long-term lens of their own geopolitical imperatives, would rather see them stay divided. Both had U.S. troops stationed on half their home soil. And like the North, East Germany suffered greatly from the loss of Soviet aid and security.

In most ways, though, the two Germanys were much better suited for reunification. By 1991, they were far more integrated than the Koreas are today, and the East was already beginning to disintegrate. East Germany had never adopted North Korea’s extreme version of totalitarianism and collectivism, and it didn’t derive its legitimacy from as intense a narrative of permanent siege by outside forces. The economic disparities between the two Koreas are also far wider. By 1991, West Germans were two to three times as wealthy as their eastern brethren, while South Koreans are estimated to be between 12 and 40 times richer than North Koreans (the North’s opacity explains the wide range in estimates). Thus, reunification was considerably less taxing for the West than it would be for the South, which likely wouldn’t enjoy the same level of outside funding for the process that the West Germans did.

Despite their age-old suspicion of a united Germany, neighboring powers like France and the United Kingdom accepted reunification in service of the broader project of European integration, with NATO and the common market diminishing the threat of German domination of the Continent. None of Korea’s neighbors have a similar cause to tolerate a process that puts a more powerful state on their doorstep.

North Korea, despite its poverty, has already proved capable of surviving without Soviet support. And though Pyongyang does not want to be beholden to Chinese patronage, this lifeline isn’t going to dry up anytime soon, given China’s ascendancy and interest in retaining the North as a buffer state. As a result, North Korea is more likely to be able to hold out on reunification if it doesn’t like the terms. By comparison, West Germany and its allies were able to gradually entice the East Germans away from the wheezing USSR, which couldn’t afford to keep up heavy subsidies to its client states anyway. For all intents and purposes, West Germany absorbed East Germany. North Korea won’t willingly follow suit. And unlike East Germany, North Korea has nukes.