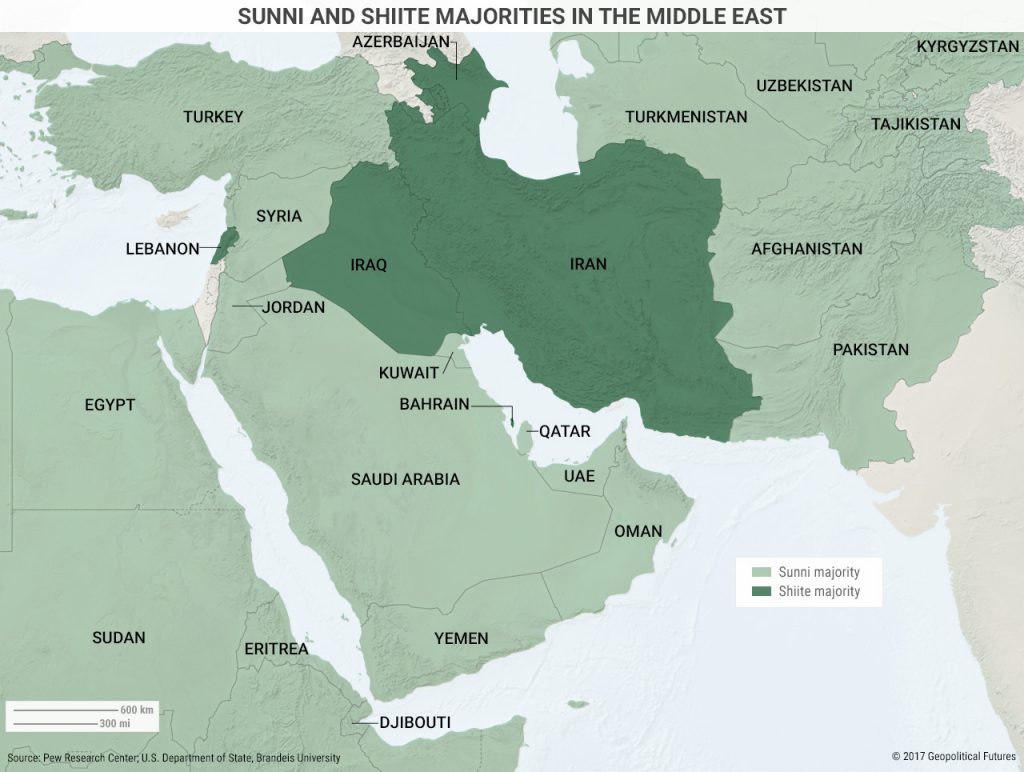

Problematic though these ethnic and sectarian differences may be for domestic Iranian politics, they also affect the geopolitics of the region. The Caucasus, the Middle East and South Asia all have large Shiite populations, but Iran alone has a government that incorporates the religious practices of the majority of its citizens. And it is surrounded by Sunni majority states that are often hostile to its interests. (There are notable exceptions, of course. Azerbaijan is mostly Shiite but has a secular government; Bahrain is mostly Shiite but has a Sunni monarchy; and Iraq is mostly Shiite but has a mostly ineffectual government.)

And so Iran doesn’t have too many options for projecting power. It can’t go east, even if it wanted to involve itself in the troubles of Afghanistan and Pakistan. It can’t go north, lest it encroach on territory traditionally under the influence of Russia. It can go only west, toward the Middle East.

But this strategy cuts both ways. The west may be the only avenue for expansion, but it is also one of the only avenues for invasion – which happened intermittently from the 3rd century to the 7th century, the 16th century and as recently as 37 years ago. Iran’s national security strategy, therefore, is to ensure that threats to its west are neutralized – no easy feat, considering most of Iran’s neighbors are majority Sunni Arab.