Originally produced on April 9, 2018 for Mauldin Economics, LLC

By George Friedman and Jacob L. Shapiro

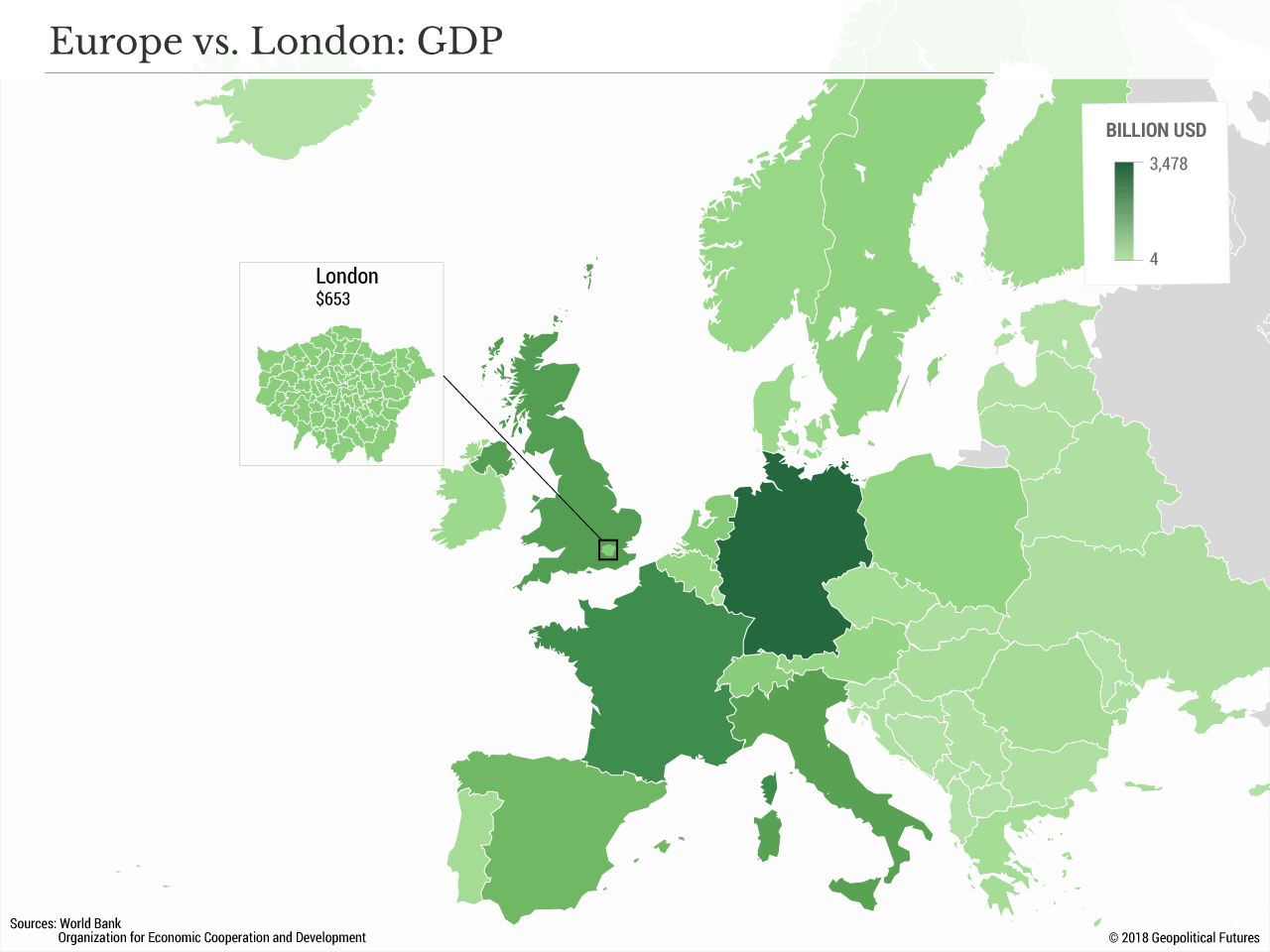

If London were a city-state, it would boast the 20th-largest national economy in the world. Its national per capita gross domestic product would be greater than that of the United States. It would be the 15th most populous country in Europe and, most important, it would have voted to remain in the European Union.

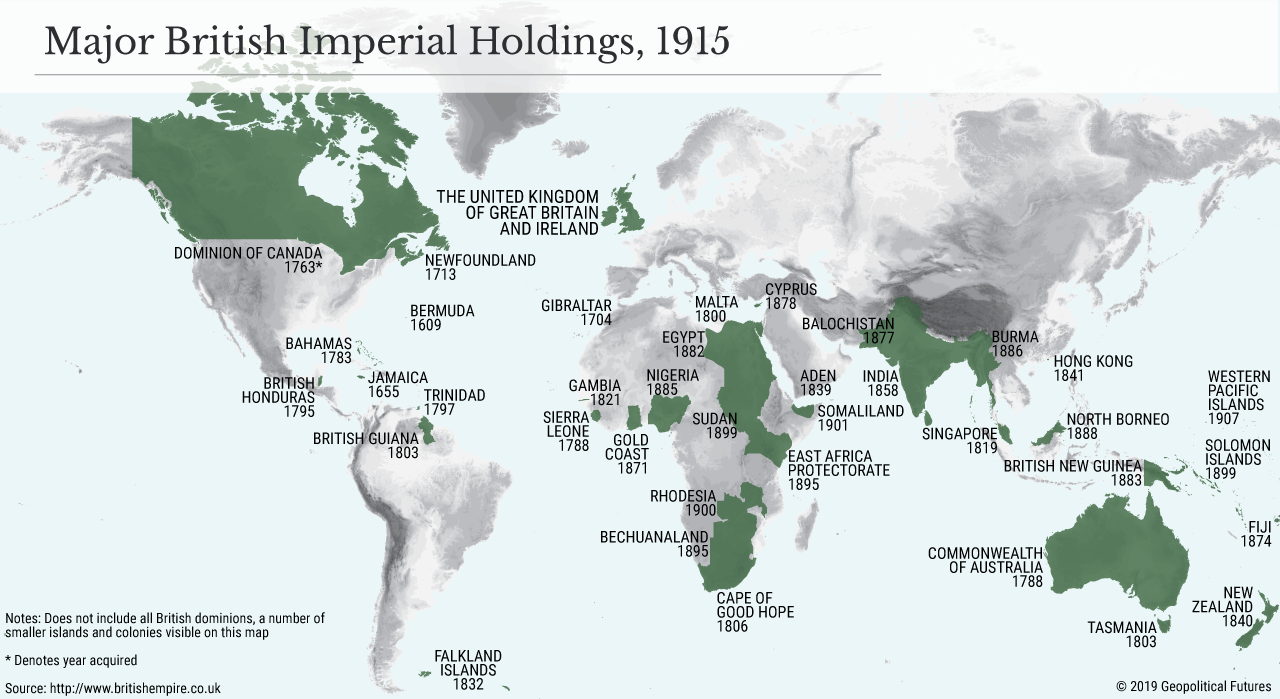

But London is not a city-state, and it can never aspire to be one. For just under a millennium, London has been the capital of England; for more than three centuries, it has been the capital of the United Kingdom; for more than a century, it was the capital of the largest empire ever conquered. London embodies the paradox of all great cities. Great cities are the ultimate expressions of their national cultures, often serving as the seat of power for millions, even billions, of people who do not actually live there. But just as often, the interests of the cities diverge from those of the rest of the nation.

Such is the case for London. The power it wields and the opportunities it offers have attracted people from all over the world. The city has become a strategic necessity for the country in which it resides. The role London plays in that strategy changes according to the necessities of the times, and it’s just as likely as not that its interests actually align with the United Kingdom’s.

Consider Brexit. No part of the United Kingdom will feel the ramifications of the UK’s departure from the EU more deeply than London, which by dint of strategic necessity became a European financial and economic powerhouse. That is why Londoners voted with the Scots and the Northern Irish to “Remain”—because London, not England, will bear the brunt of the short-term disruptions to come.

But London has transformed itself many times before, and there’s no reason to believe it will be daunted this time around. As much as it would like to remain Europe’s primary financial capital, London has been and always will be a national capital.

Bridgehead Revisited

For the first several centuries of Britain’s existence, much of the world used London as a bridgehead for invasion. But after the Industrial Revolution, when the British Empire reached the height of its power, London instead became a bridgehead for England to invade much of the world.

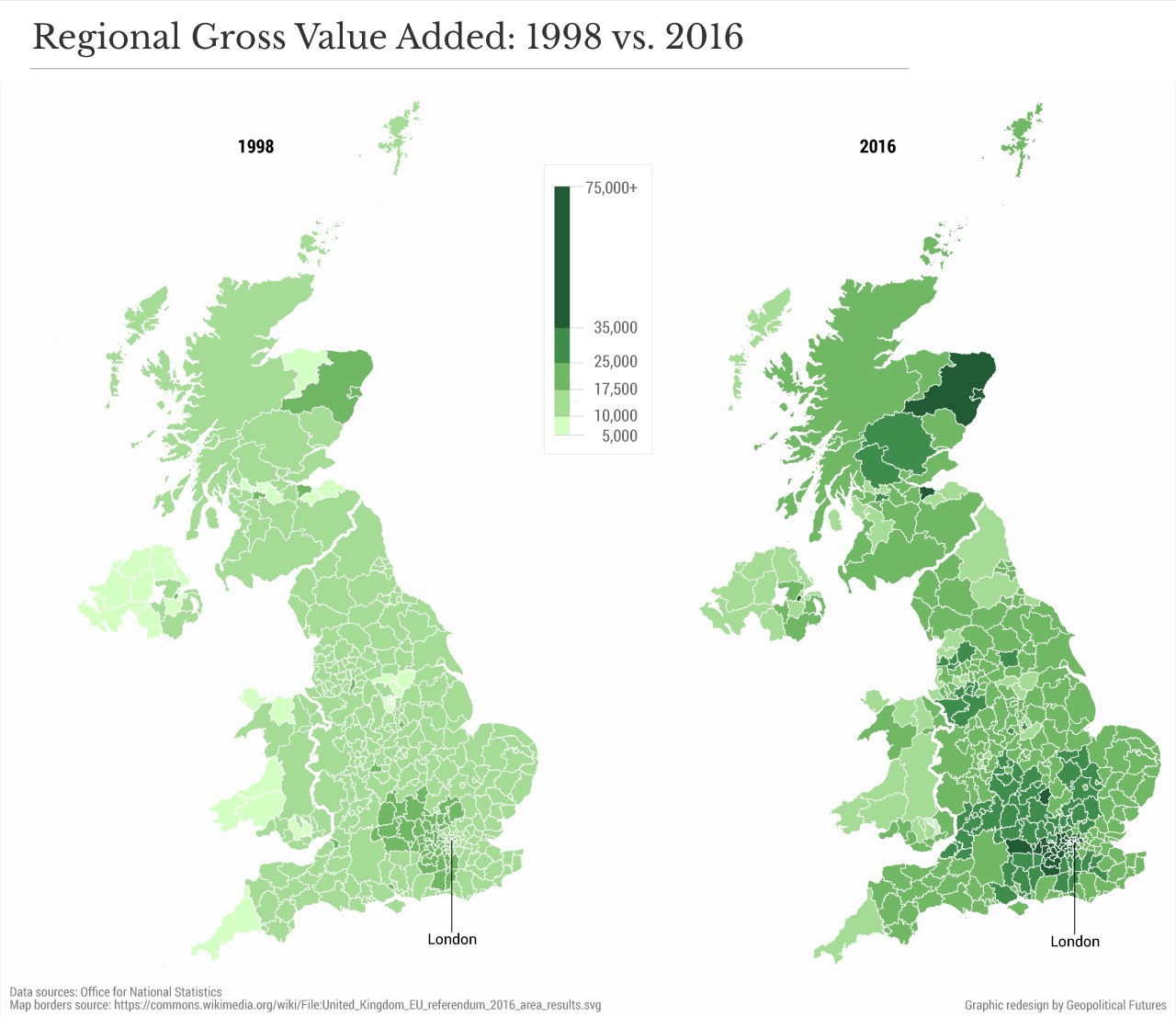

The city had grown only more powerful since it became England’s capital. The majority of British wealth and power became concentrated in southern England and, to a lesser extent, the Midlands, Britain’s most fertile areas. The Greater London area was by far the richest and most populous simply because it was a trade hub for the country and, by extension, the rest of the world.

Advances in agricultural technology enabled people around the world to live longer. The resultant population boom raised demand for virtually all goods. At first, English farmers who worked in cottage industries could not keep up with demand, so huge factories were created to keep pace. Later, farmers in southeast Britain began to leave their homes for the cities—at first, mainly London—to seek out better paying jobs. By 1801, London had a population of 960,000. By 1911, it had a population of 7 million.

London became even more important in its role as Great Britain’s main port. Great Britain simply did not possess enough raw materials to keep pace with demand. And so it began to import larger and larger amounts of raw materials from its imperial possessions. Even the imperial possessions it could not keep began trading with Great Britain on a massive scale. In 1784, the US exported eight bags of cotton to England. (That is literally what the statistics say, without further clarification.) Within 15 years, the US was exporting 40,000 bales of cotton to England each year, and by 1900, that figure had risen to 7 million. The story was much the same for other commodities like sugar and tobacco.

London was not the only city to reap the benefits, of course. By 1900, Glasgow, Manchester, and Liverpool all had populations of over 1 million people. Northwestern England, which before had been a relative backwater, became Industrial England. New nodes of political and economic power that had not existed before sprang into being, the effects of which became truly apparent only in the decades following World War II. But in the 19th century, none came close to rivaling London’s immense wealth and power.

London was the main seat of political power and had also become a center of commerce. And it was the largest manufacturing town in the country that had been the vanguard of the Industrial Revolution.

Ground Zero of a Revolution

After World War II, London was a shell of its former self. The UK kept many of the trappings of imperial power, of course. It developed nuclear weapons, maintained a relatively impressive military, and held a permanent position on the UN Security Council. But in large measure, the UK’s fate became directly tied to Europe’s fate, and no region of the UK could coexist as easily as London could as both capital of England and European hub. British power became metropolitan power, and London remade itself once again, as it had so many times in the past, to meet the challenges of the day. With all the ingenuity and cosmopolitanism it had acquired as an imperial capital, London built itself up at a dizzying pace and became Europe’s—and the world’s—pre-eminent financial center.

It regained its place as a global financial center precisely because London had been ground zero of the Industrial Revolution. Much of the infrastructure necessary for finance was already present in London, and compared to all other potential challengers, the regulatory framework was more predictable and friendly to investment in London than anywhere else in the world. In relatively short order, it put its wealth of experience in global finance to work and so was able to recover from World War II more quickly than other European cities.

It wasn’t easy to get there—the UK was heavily indebted until the 1960s—but when it did, it arrived with authority. It became a global banking hub, boasting the largest foreign-exchange market in the world, and it was already one of the world’s oldest insurance markets. For the rest of the UK, the sterling was used daily, but London profited from specializing in the trading of offshore currencies, especially dollars held outside of America.

Notably, London soared higher than ever because of the Maastricht Treaty, which created the European Union and paved the way for the adoption of the euro. The United Kingdom never adopted the euro itself, but that didn’t stop London from financially dominating the European Union. According to the House of Commons Library, financial and insurance services accounted for 7.2% (124.2 billion pounds) of the United Kingdom’s total gross value added in 2016—a fairly small proportion in the UK’s overall economy. London, however, accounted for 51% of that total. In fact, when you compare industrial variation in total gross value added of UK combined authorities, London presents a much different picture than the rest of England. Roughly 14% of London’s GVA came from the finance and insurance industry, while just 2.1% came from manufacturing. The opposite is true for every other UK combined authority.

Some 2.2 million jobs in the UK are related to financial and related professional services. About 47% of those jobs are located in London and in the southeast, according to TheCityUK. No other region of the UK has a percentage higher than 10%; Wales and Northern Ireland boast only 4%. Moreover, the jobs in London are generally geared toward international finance, whereas in other regions they are focused more on British finance. The UK’s global value added per head has obviously benefited from its position relative to the EU—but here again, London has experienced those gains to a far greater extent than the rest of the country.

London’s time as the undisputed king of European finance ended on June 23, 2016, when the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union. There were many precursors to this change, but one was more important than all the others, and it is perhaps the most overlooked: the collapse of the Soviet Union and the reunification of East and West Germany. Just as German unification in 1871 defined European history for decades to come, Germany’s second unification in 1990 has also defined Europe’s future—a future that Britain could no longer control. Remaining in the EU would have meant subordinating British interests to German interests, and there was never going to be much of a future in that.

The more daunting challenge emanating from across the channel is the reactivation of great power politics. The most disastrous periods in London’s history have come when Great Britain did not have the power to repel foreign invaders. Ironically, the UK’s decision to leave the EU underscores a far bigger threat to London than international banks leaving the city or tough German negotiating tactics: the attendant conflicts and rivalries that have delegitimized the European Union.

Against these national forces, London is relatively powerless. Its fate rests in the hands of the nation it sustains, a nation that can in turn protect London only by maintaining old allies such as the United States and developing new ones in Europe and beyond. The fate of the UK, meanwhile, depends on London’s ability to find new ways to create and share wealth with future generations of British citizens.

For more than a thousand years, London has been the UK, or some iteration of it. Though the two see the world differently right now, they can afford to. The future will not be as kind, and when that future comes, the interests of nation and city will be joined once more.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East