By George Friedman

Summary France and Germany are growing further apart. When it comes to their approach to security threats, military operations and spending priorities, the two countries increasingly diverge. The differences between Paris and Berlin underline Europe’s fragmentation.

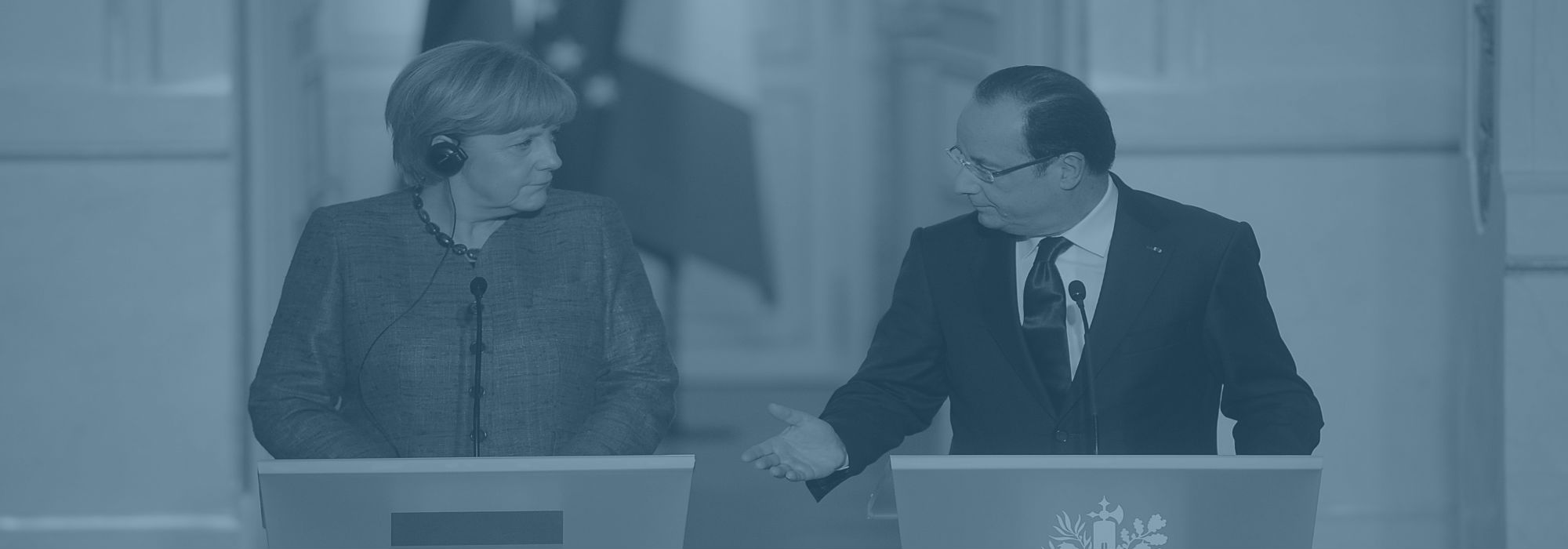

One day before a joint meeting of French and German officials on April 7, French President François Hollande said in an interview with the German newspaper Bild, “Our two countries must agree to a budgetary effort on defense. And to act outside Europe. Let’s not rely on another power, even a friendly one, to do away with terrorism.” This is a statement that requires serious consideration.

The European Union was built on a core concept. The origin of European conflict, going back to 1871, has been the divergent interests of France and Germany. The post-World War II solution was to integrate the French and German economies so deeply that political divergence became impossible. The European Union has lost its cohesion, and the alignment between France and Germany is holding it together. The union is not what it once was, but so long as these two countries retain a fundamental alignment, it is reasonable to say that all is not lost. However, relations between the two countries have come under strain, and anything that adds to the existing tension raises red flags. The statement made by the French president on the eve of a meeting with the Germans to showcase harmony is a red flag.

The attacks in Paris and Brussels have posed a fundamental question for France. It cannot simply accept this threat, but must do something about it. There are two parts to dealing with this threat. First, the conflicts that are raging in the Middle East must be brought under some control. Second, the issue of radicalization in Muslim communities must in some way be addressed. In the Bild interview, Hollande made the latter clear, although how he will respond to this issue is uncertain. But for the French, building a European military force around France and Germany is the necessary precondition for any solution to Europe’s growing challenges.

This goes counter to Germany’s fundamental sense of self and its interests. For Germany, building a military force after World War II has been problematic. It had one during the Cold War, but in many ways it was not under Germany’s command but NATO’s. It did not have the feel of a resurgent European military because it was, in the end, the junior partner of the United States.

Hollande specifically said that France and Germany could not depend on a third power, no matter how friendly, to fight their battles. He clearly was referring to the United States. Collaborating on defense budgets, with each nation contributing based on economic size, would mean that Germany would be both the leading economic and military power in Europe. Within the EU, Germany is first among equals. Creating a substantial military force would cement that. And that raises for Germans the specter of a return to what must never be again.

There is another reason for the divergence between the two countries, which explains why the French are not more frightened of this proposal than they should be. The French want an expansionary budgetary policy, while the Germans want to restrain spending. Defense spending would generate budget deficits, but this would also stimulate Europe’s economy. German unemployment at the moment is 4.5 percent, while France’s is much higher. Germany, at full employment, fears inflation, but France fears stagnation.

There is a psychological divergence as well. The French are responding to terror attacks with a sense of helplessness. The Germans have not been attacked in the same way and are more sanguine. This reminds me of the U.S. response to 9/11 and the European sense at the time that the U.S. was overreacting. The schism between those who have been victimized and those who have not is profound. One must act, while the other sees no urgency and cautions prudence.

The implicit reference to the United States is also important here. France is acknowledging that Europe cannot simply rely on the U.S. to fight wars with the jihadists. Indeed, the U.S. has shifted away from multidivisional ground combat. We can see that in Syria. The Americans have learned that it is easy to defeat a conventional military force, as it did in Iraq. However, the Iraqi military fragmented and evolved into a resistance that would require massive force to even attempt suppressing. The United States simply does not have a force of that size. It will not engage on the ground in Syria, confining itself to special operations and airstrikes. In a way, the Americans have learned the lesson the French have been trying to teach them since 2003. But on the other hand, the French have now learned the reality the Americans have lived with since 2001.

In addition, Donald Trump is far from the only American who thinks NATO, in its current form, doesn’t work. The population of the European Union is just 500 million, nearly 200 million more than the United States. The EU’s GDP is larger than the American GDP. There is no reason why Europe’s defense capability should not at least be the equal of the United States. It was a given in the 1950s or 1960s that Europe’s contribution should be a small fraction of the United States’ contribution. In 2016, there is no justification for the disparity.

The disparity exists because the Europeans have not seen themselves as having major strategic threats or interests that the United States would not deal with. Whether it was the the Middle East or Ukraine, the Europeans made the assumption that the United States would accept the risk and the burden of dealing with the threat and permit the Europeans to contribute what they were comfortable with. It is simply not clear that the United States will continue in this role. It may, but the time it would take for the U.S. to create an enhanced military force is substantial. U.S. policy, like all countries’ policies, is changeable and shows signs of changing. Hence Hollande’s warning.

There are two Europes speaking here. One, the Europe that needs stimulus, is frightened by the jihadist threat and views the Middle East as an arena where it might have to fight – and might not be able to count on the United States. The other Europe fears stimulus, is not nearly as frightened by the jihadist threat and can’t imagine fighting on a large scale in the Middle East.

That these two Europes are represented by France and Germany indicates the depth of Europe’s fragmentation. Embedded in Hollande’s statement is the distance that separates these two nations. Any challenges to the EU from Britain or Poland or Greece are trivial matters compared to the differences building up between France and Germany.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East