Originally produced on Dec. 14, 2016 for Mauldin Economics, LLC

George Friedman and Jacob L. Shapiro

One of the biggest challenges in writing forecasts is clearly communicating our predications for the coming year. There is a certain level of background and analysis that goes into forecasting geopolitics, but often, that background and analysis can serve as either an intellectual crutch or a way of using a lot of words without actually making a call one way or another.

That’s why our annual forecasts go through multiple phases of editing. Our forecast for 2017 was published just this week. But our work on the forecast began in early October, with a massive 50-page document filled with questions, research, and findings. This master document was then scrutinized, debated, and whittled down, sharper and sharper… until what was left (hopefully) was a concise description of the world in 2017, as we see it.

We aim for accuracy, and as you can see from previous report cards on our work, we are pretty good at what we do. Our full report card for 2016 will be published next week, but in the meantime, subscribers can check out our mid-year evaluation here.

But another aim that is almost as important is to be very clear about what we are forecasting. We would rather be wrong and have made a clear forecast than offer a vaguely worded “prediction” that is unfalsifiable.

Therefore, we spend less time explaining how we arrived at a given conclusion, and more time clearly stating what we think is going to happen and how that will shape the world. A forecast is not an analysis—it is the culmination of analysis. That means that a certain amount of information about how we arrived at a particular forecast is always left out. If it weren’t, the forecast would read like a volume of Tolstoy, and no matter how brilliant Tolstoy was, his writing style is not well suited for forecasting.

So, for the next four or so installments of This Week in Geopolitics, we’re going to take a closer look at some of our most important forecasts for 2017. You can read all of them in our 24-page, subscribers-only report, The World in 2017—yours free of charge if you try a Geopolitical Futures subscription today. To keep things fair for our paid subscribers, we won’t go into great depth on the actual forecasts here—instead, we’ll focus on the analysis and research that led us to some of our most important conclusions.

We’ll kick off this series by looking at the current situation in Russia, which we believe is in for a difficult year.

Russia’s Military Capability

We began the forecasting process with Russia by looking at the country’s military capability. Russia has intervened in Syria to great fanfare, and while it has demonstrated undeniable improvements in some of its capabilities, the Russian military is far weaker than most make it out to be. Our 2016 forecast predicted a frozen conflict in Ukraine, and we came to the conclusion that this frozen conflict will be formalized in 2017 by answering a very basic question: What is the Russian military capability in Ukraine and in general?

The answer is found not by looking at events pertaining to the Ukrainian revolution in 2014, but rather the performance of the Russian military in the 2008 Georgia War. Russia achieved all of its strategic objectives in that five-day war, but serious deficiencies in Russian capabilities were revealed. Operational and tactical logistics left much to be desired, as the Russians had serious difficulties maintaining supply lines for food, fuel, and ammunition. Much of Russia’s military equipment was old and falling apart, Russian suppression of enemy air defenses (SEAD) and electronic warfare capabilities were deficient, and use of precision-guided munitions was rare. Joint operational planning between different services was either nonexistent or ineffective.

After the war, Russia set out on an ambitious and vast military modernization program, reforming everything from doctrine to training to weapons. Russia set clear goals for reducing the number of conscript soldiers to professionalize the force. The 10-year State Armaments Program, announced by President Vladimir Putin in 2010, allocated 19.4 trillion rubles (worth $698.4 billion at the time) to revamp the equipment and weapons used by the Russian armed forces, and Russia’s military expenditures have been increasing both in absolute terms and as a percent of Russia’s GDP ever since.

Russia has taken some impressive steps forward. In 2008, it is unlikely Russia could have fielded a force and deployed it in Syria as it did in 2015. Of all the weapons Russia used in Syria, roughly 20% have been precision-guided munitions, which shows progress… but it also shows how much room Russia has to grow. Russia has deployed unmanned aerial vehicles to help with intelligence gathering, and both SEAD and joint inter-service operations have improved. According to Russian military officials, conscripts in the military have been reduced from roughly 600,000 in 2011, to 200,000 by the end of 2016.

These improvements and the media campaign around the Russian intervention, however, obscure the two most important elements to consider in evaluating the Russian military. First, despite these improvements, Russia has neither the military capability nor the political capital to conquer Ukraine, even if it wanted to. Russia beat Georgia because Georgia is a small country and Russia could overwhelm the Georgians with larger numbers. Ukraine is eight times the size of Georgia in terms of total land and can field a much larger infantry force. Many of Russia’s Rapid Reaction Forces that would be mobilized in such an action still consist of significant numbers of conscripts. Even if Russia could blitz its way to Kiev, it couldn’t hold the country, considering the long supply lines and Ukraine’s large, hostile population. And if the US or NATO decided to intervene, Russia would require even greater forces.

Second, Putin and the Russian government are aware of these limitations. Since 2008, they have been doing everything possible to modernize the Russian armed forces and to reach, if not parity, then a level of strength that could give them more strategic options. That has meant increasing military spending.

While Russia was flush with oil money, that was a perfectly logical plan. But Russia was not expecting oil prices to collapse in 2014. Russia had planned a budget on the then-conservative estimate that oil wouldn’t fall below $82 a barrel. Oil has averaged between $34 and $35 a barrel in 2016, and there’s no reason to expect the oversupplied market to give Russia significant relief in the coming year. Modernizing Russia’s forces is one of the top priorities for the government in the next three years, but it’s not clear if Russia has the money to spend.

The Russian Economy

The main issue for Russia in 2017 is not going to be a military one. Russia does not want to get bogged down in Syria, so it will be looking to extricate itself from that conflict. Russia cannot fix its Ukraine problem through force, so it will try to reach a settlement that will allow the status quo to remain in place. As long as Kiev remains neutral and not a basing point for major US and NATO assets, the Russians will be content, though uncomfortable. The problem for Russia is that its economy is in a shambles, and it is trying to pour money into modernizing the military at the same time that disturbing cracks in the Russian economy are beginning to show. Let’s look at two graphics that demonstrate just how challenging the current situation is.

This is a simple chart of the exchange rate between the ruble and the dollar in the last five years. Since July 2014, the ruble has lost almost 50% of its value. In 2010, Putin promised to spend 19 trillion rubles on upgrading the Russian military, which was equivalent to almost $700 billion at the time. Today, 19 trillion rubles is worth only $303 billion. Real wages have been declining since 2014. Inflation, at this time last year, was almost 13%, and though it has stabilized around 6% in recent months, the ruble is still under a lot of pressure.

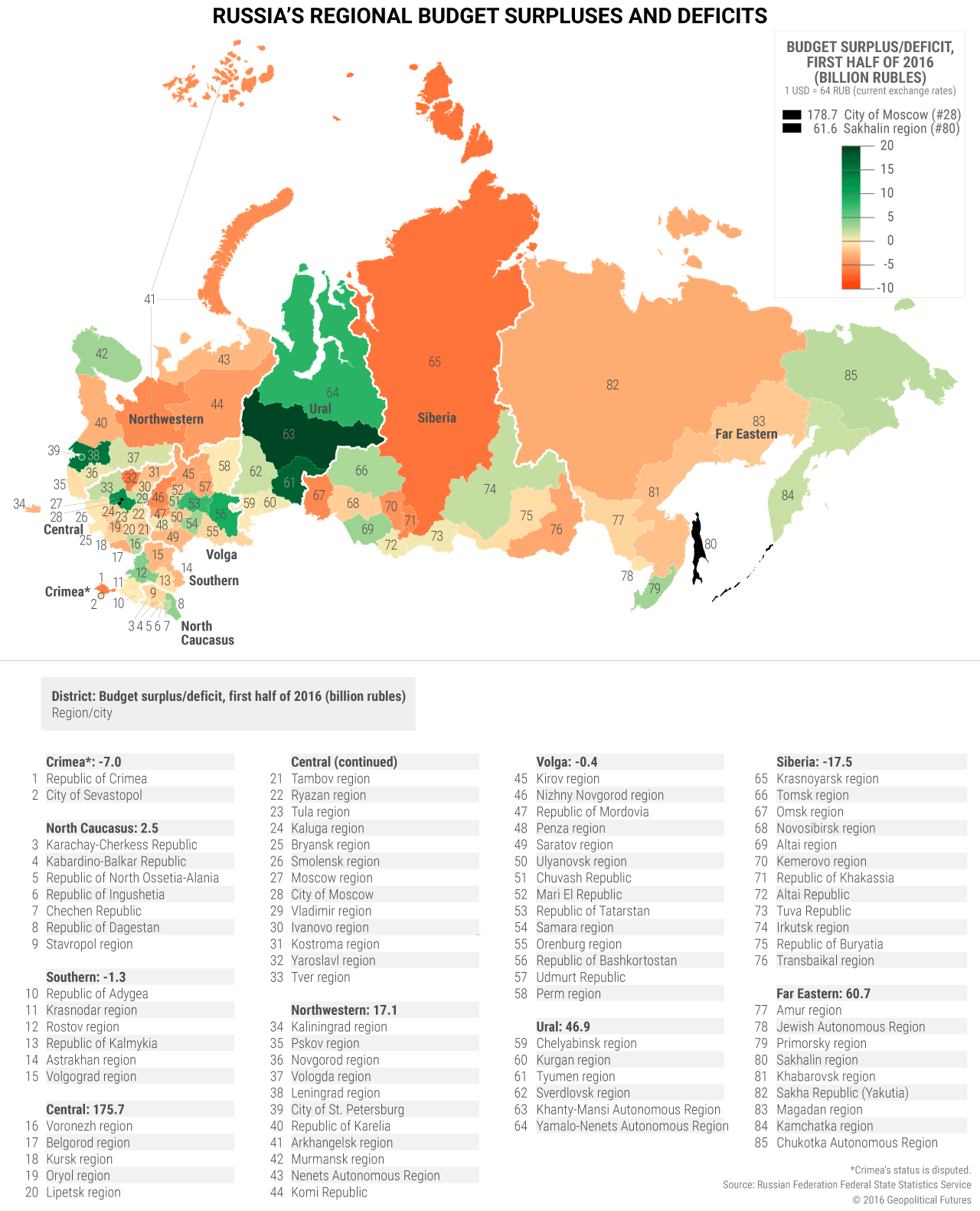

This graphic shows the current state of Russia’s regional budgets, and the picture is not pretty. Major oil-producing regions as well as Moscow are doing all right, but large swaths of the rest of the country are running regional deficits. The central government in Moscow is also struggling, reportedly cutting all federal ministry budgets by 10%. While spokesmen in Russia’s Defense Ministry have said that defense spending will be cut by 5%, this is impossible to confirm because some parts of the Russian budget are classified and those defense expenses are likely hidden. Russia’s Ministry of Finance says that Russia’s Reserve Fund (which totaled 28.6 billion rubles in 2008) will be fully spent by the end of 2017 and that the country will start dipping into its National Wealth Fund to cover its budget deficits.

In addition to these larger indicators, we have seen disturbing smaller indicators of a struggling economy. A few weeks ago, protests occurred in one oil-producing region in Ural Federal District due to economic dissatisfaction, and in another region due to unpaid wages and malfunctioning heating equipment shortly before winter came in earnest. Russia has been shutting down banks at an increasing rate and blaming them for irresponsible lending practices. This has prompted over 2.7 million more people to apply for deposit insurance in the last five years than the previous five years, which could be a sign that the banking sector is under severe pressure.

The Forecast

These are the basic building blocks, and once they were identified, the forecast essentially wrote itself. Having defined Russian military capabilities, we were able to identify Russia’s political and strategic objectives in Ukraine, Syria, and elsewhere in the year ahead.