The last two years have been the toughest for Iran since its 1979 revolution. Most Iranians have been negatively affected by Western sanctions as well as the ongoing pandemic. At least one-third of the population lives in abject poverty. Malnutrition is rampant, especially among children in rural areas. Meat is becoming increasingly scarce, and the price of food staples such as rice, grains and legumes is skyrocketing, with the consumer price index for food increasing by 67 percent in January compared to the previous year. More than 1.2 million Iranians lost their jobs because of COVID-19, divorce rates have risen by 7 percent and the number of people treated in rehabilitation centers has jumped to 663,000 from 417,000.

Because of Iran’s mounting economic and social problems, the mere prospect of reviving the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), following U.S. President Joe Biden’s election last year, is a godsend for Iran. While the acquisition of nuclear weapons continues to be a strategic objective for Iran, the country is in no rush to achieve it, considering that doing so could jeopardize its ability to resuscitate its economy, consolidate its regional influence and build its conventional military might. In the immediate term, its main objectives are to salvage the regime, improve standards of living and relaunch the economy, while also maintaining and accelerating its regional gains. Nuclear weapons can wait.

What Iran Really Wants

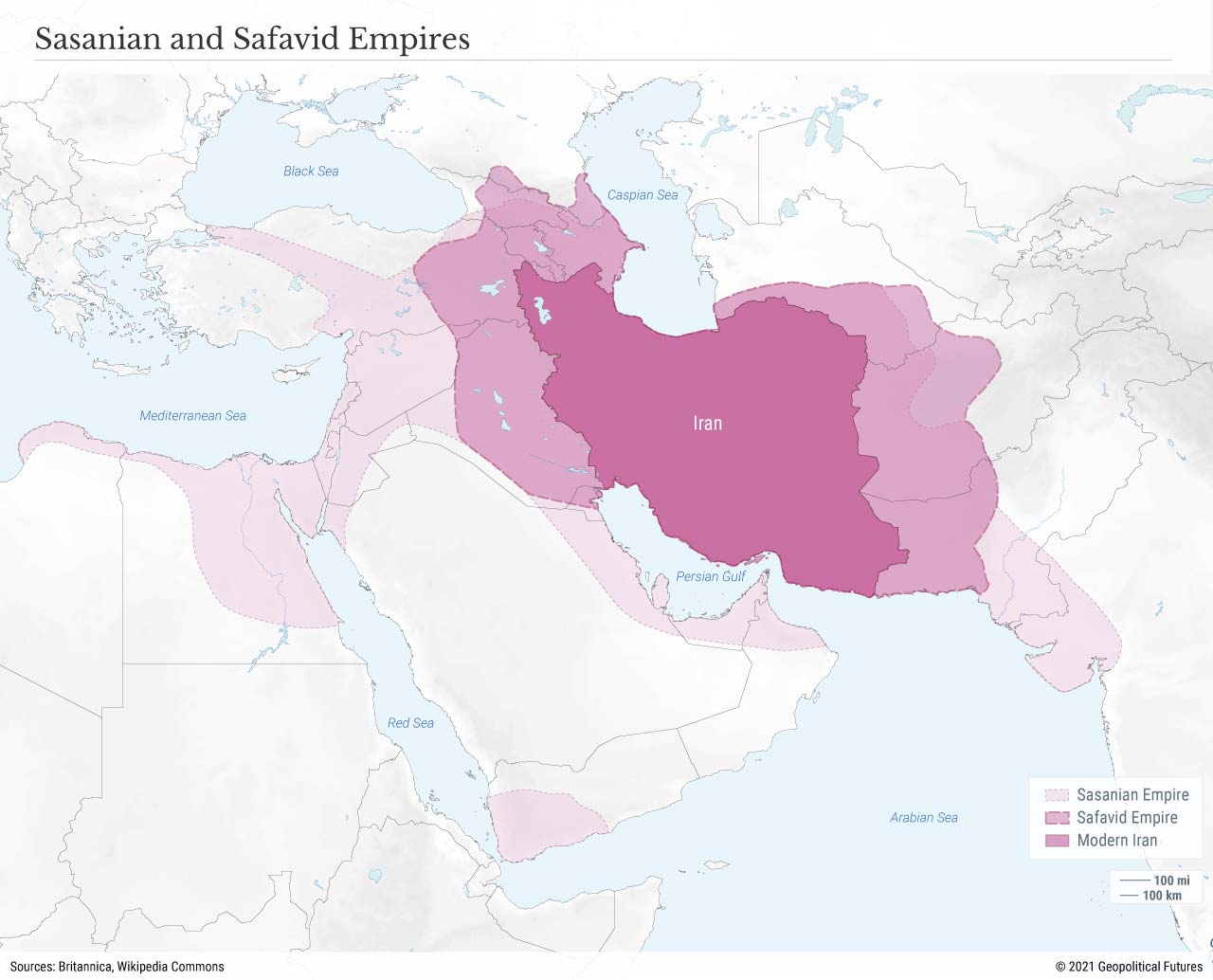

Over the past six centuries, Iran has suffered military defeats, territorial losses, foreign power manipulation and, in the 20th century, occupation by British and Soviet troops. It also, however, has a long history of territorial expansion and imperial drive. The Sasanian Empire (224-651) seized the Caucasus, the entire coastline of the Arabian Peninsula, Egypt and Asia Minor, and even reached India’s doorstep. In the 16th century, the Safavids built an empire that included the Caucasus, though they gradually lost territory to czarist Russia, and their Qajar successors lost what territory remained. The revolutionary clerics regretted dismantling Iran’s nuclear program and its formidable army and air force, which the shah had built with U.S. backing, arguing that Iraq would not have attacked Iran in 1980 had they remained intact.

Iran now wants to become a regional hegemon once again. Its leaders see Iran as entitled to become the leader of the Middle East, or at least an equal of Israel, which is currently the region’s only real power. Its challenge, however, is that Israel is resistant to having any nation rise to its level, and so has actively pushed back against Iranian expansionism. But the Iranians are playing the long game and will bide their time. As the Israelis understand better than most, there’s a lot more to Iranian ambitions than nuclear weapons.

The Nuclear Issue in Perspective

Every U.S. administration since the Iranian Revolution has been keen on avoiding direct military confrontation with Iran. Like former President Donald Trump, Biden sees the divisive issues with Tehran – its nuclear and missile programs and burgeoning regional influence – as part of the same package. The only difference between the two presidents is that Biden is more flexible, believing that there’s no need to weaken an already emaciated Iran.

Biden is keen on resolving the standoff over Iran’s nuclear program through diplomacy and is focused on reaching a better deal than the JCPOA, which in reality would have only delayed Tehran’s acquisition of nuclear weapons. The Biden administration knows that Iran’s ballistic missile program and regional policy are nonnegotiable, and believes Tehran’s regional meddling is beyond the scope of the nuclear talks, important as it may be for Middle East stability. Trump, on the other hand, chose to apply a maximum pressure campaign, hoping to force Iran to sign a new, more rigorous deal that would further slow Iran’s nuclear program while also downsizing its ballistic missile program and curtailing its regional adventurism.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is also opposed to merely renegotiating the nuclear deal. But Israel’s threats of military action are more posturing than warning of imminent conflict. Realizing that Biden cannot ignore Israel’s concerns, Israel is trying to secure more concessions from Iran by voicing its opposition to nuclear talks. Iranian officials are also adept at the politics of brinkmanship. As expected, they reached a temporary, last-minute deal with the International Atomic Energy Agency to ensure Iran’s nuclear sites were still monitored even after it suspended compliance with the JCPOA’s voluntary protocol. Last December, Iran’s parliament approved a bill to stop cooperation with the agency and increase uranium enrichment to 20 percent. Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif said that the government respected the parliament’s decision but would continue cooperation with the atomic agency, adding that the parliament’s decision is reversible if the U.S. cooperates.

For Iran, acquiring nuclear weapons is not an immediate goal. The dispute over its nuclear program has been ongoing for more than 15 years, and it hasn’t manufactured a nuclear weapon yet. Indeed, lifting sanctions takes precedence over everything else – even acquiring nuclear arms – because the ruling mullahs want to modernize the economy and provide for the basic needs of Iran’s restive population.

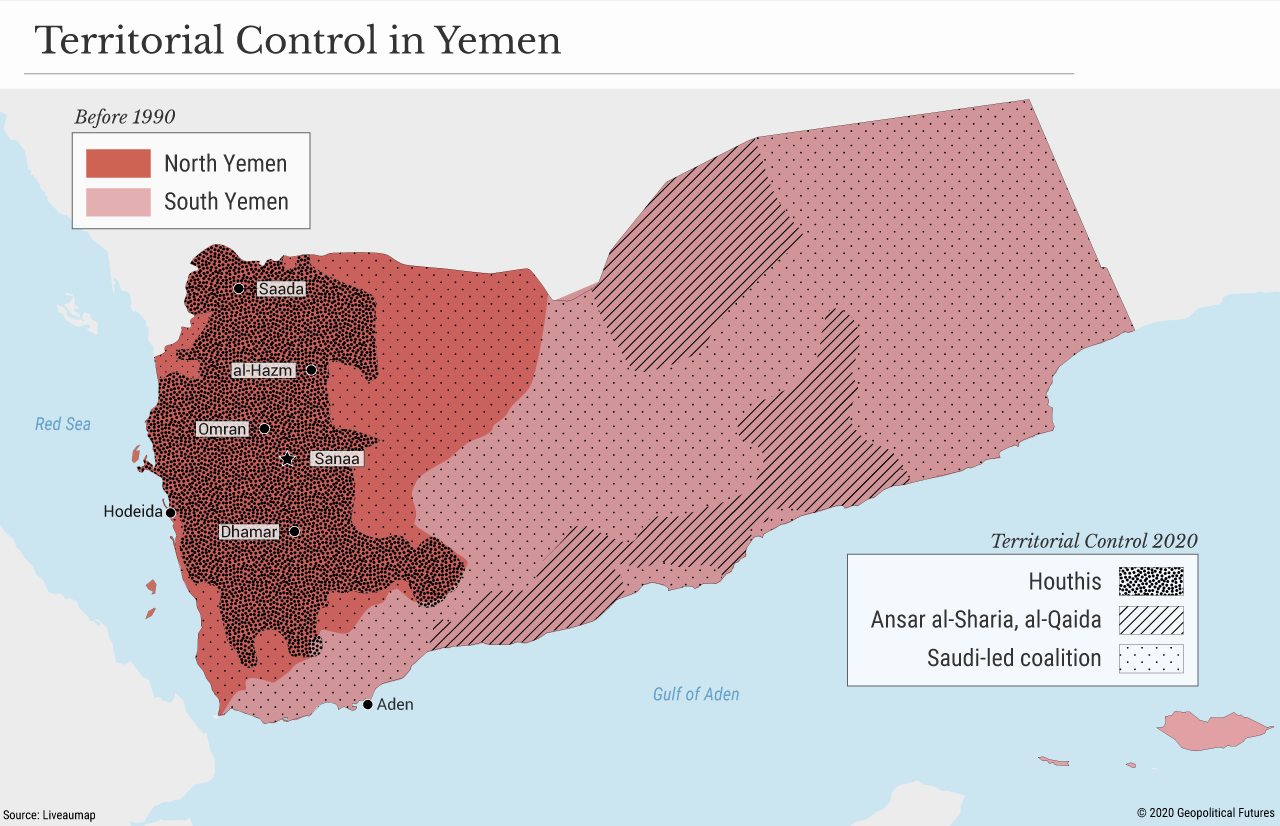

There is a real concern, however, that lifting sanctions would enable Iran to consolidate its regional presence and further weaken embattled Saudi Arabia, which has been hit by several drone attacks from Iran-linked groups like the Houthis in Yemen. The Houthis are launching the final battle in Yemen’s oil-rich Marib province, the last remaining bastion of control for President Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi. If their offensive succeeds, Yemen as we know it would no longer exist. The United Arab Emirates already controls the south, the Houthis would tighten their grip on the north, and Saudi Arabia would emerge as the biggest loser.

But Washington is gradually losing interest in Saudi Arabia as a country of vital national interest. Former President Barack Obama once called Saudi Arabia a free-rider, without directly naming it, and Trump, during his 2016 election campaign, said, “If Saudi Arabia was without the cloak of American protection, I don’t think it would be around.” For his part, Biden said the U.S. would halt arms shipments to Saudi Arabia and terminate support for its war in Yemen. He also withdrew Trump’s letters to the U.N. that led to the reinstatement of Iran sanctions and expressed his willingness to work with the Europeans to reach a new nuclear deal. Biden’s Middle East policy seeks to reduce regional tensions, deal separately with various explosive issues and introduce an elaborate system of balances that does not exclude Iran. Regardless of who rules Iran, the country is essential to Washington’s balance of power policy.

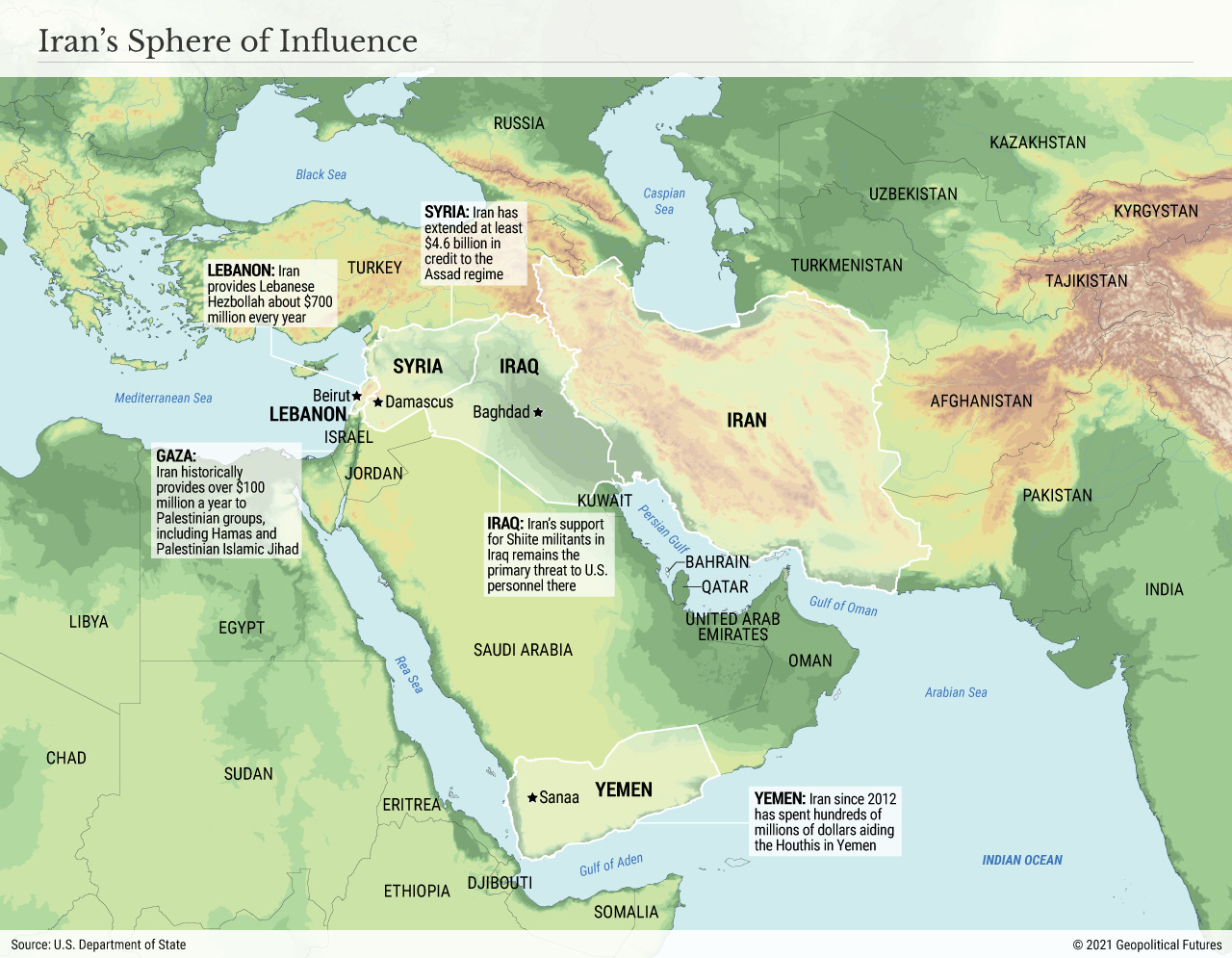

Indeed, it’s too late to end Iran’s meddling in its neighbors’ affairs anyway. In Iraq, the government says that the pro-Iran Popular Mobilization Forces report to the Ministry of Interior. They receive their budget from the central government in Baghdad – which amounted to $1.6 billion in 2020. In Lebanon, Hezbollah is part of the political system and runs Lebanon along with its Maronite Christian ally, the Free Patriotic Movement. In Yemen, the Houthis have been removed from the U.S. list of terrorist groups.

Iran will resist any attempt to cut it off from its regional proxies, without whose support it cannot realize its regional ambitions. Tehran’s Shiite Arab allies are more crucial than its nuclear program for expanding its sphere of influence. Iran is still militarily weak, and it needs allies who can fight on its behalf. The more Iran organizes military exercises and announces breakthrough defense innovations, the more it reveals its inability and unwillingness to get involved in a general war. As it has been doing since the revolution, it prefers to fight through proxies, be they in Lebanon, Yemen, Syria or Iraq.

Inevitable Domestic Change

Despite the facade of cohesion, state resolve and military preparedness, Iran is more vulnerable than ever. Endemic bureaucratic corruption, poor economic planning, austere sanctions and the pandemic have nearly crippled the country and exposed its weakness. Iran’s reformists accuse power-wielding conservatives of benefiting from the sanctions through their parallel economy, whose profits they claim run around $25 billion annually. Iran’s ruling conservatives probably face more problems at home than abroad, with many Iranians frustrated by the lack of action and preferring a secular and democratic political system to replace the Wilayat al-Faqih system. Some Iranian intellectuals, academics, political activists and former officials even expressed hope that Trump would win a second term to increase the pressure on the regime.

Over the past 50 years, Iranian society has changed markedly. Even though 90 percent of its population is Shiite, according to statistical yearbooks, only 32 percent describe themselves as Shiites. Most others profess no religious affiliation or see themselves as agnostic, atheist or Zoroastrian. The regime is not facing an existential threat, and it can rely on its extensive coercive powers to suppress protests. The dilemma of the ayatollah and the regime is that they are ruling a population that not only resents their religious ideology but is continuously drifting away from them.