Originally produced on Feb. 26, 2018 for Mauldin Economics, LLC

By George Friedman and Xander Snyder

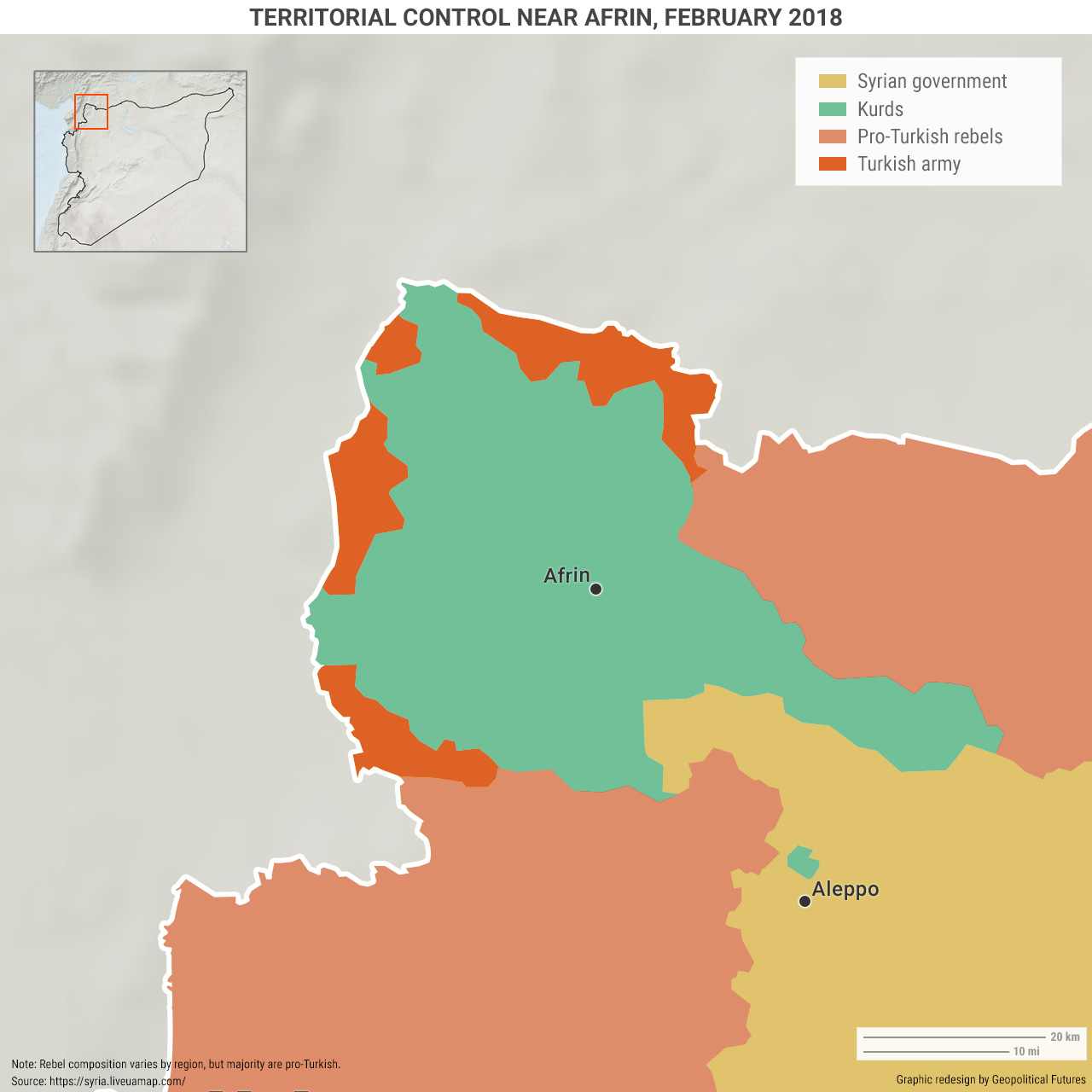

Turkey’s invasion of Afrin in northern Syria has redrawn the established lines of battle. Turkey proposed cooperation with the United States in Afrin and Manbij, both of which are held by Syrian Kurds—whom the US has been supporting and the Turks consider hostile. Though no formal agreement has been reached, US Secretary of Defense James Mattis said the US would work with Turkey to coordinate their actions in Syria. Then, the Syrian Kurds apparently invited pro-regime forces into Afrin to help fight back against the Turkish assault.

Joining the Fray

With Turkey joining the fray in Afrin and inching closer to Aleppo, a critical city over which Syrian forces have already fought a bloody battle, Bashar al-Assad has a choice: either escalate his military conflict with Turkey and its proxies or come to a settlement. To win a military victory in the region, Assad would need to move his forces along the southern edge of Afrin until they reach the Turkish border in the west and then turn farther south until pro-Turkish forces in Idlib—a region largely controlled by another Turkish proxy, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham—are surrounded. Assad will try to encircle Turkish proxies in Idlib and cut off their supply routes to Turkey.

From the regime’s perspective, therefore, working with the Kurds makes sense. It can use the 8,000–10,000 Kurdish fighters from the People’s Protection Units (YPG) in Afrin to repel the Turkish invasion and avoid expending its own resources. It also makes sense for the Kurds, who are facing a Turkish assault with few allies, since the US has said it will not support the YPG in Afrin.

But Turkey has its own plans to surround the YPG and cut off access to its allies. On Feb. 20, Erdogan announced that the Turkish military would attempt to envelop Afrin in the next several days, blocking the YPG from receiving support from pro-Assad forces. Turkey and Assad are therefore applying the same strategy to different regions, while trying to avoid a confrontation that could draw in more outside powers and escalate the conflict.

This situation could give rise to a tactical settlement in Afrin. Faced with the risk of a far bloodier battle than it anticipated, Turkey may be willing to halt its advance if the Syrian regime—and by extension, Iran and Russia—agrees to move the Kurds out of Afrin and Manbij to an area east of the Euphrates, and if it could also guarantee to control the Kurds’ actions thereafter. The Syrian government could then take control of areas that have been held by semi-autonomous Kurdish entities for several years. The Syrian Kurds might also agree to this arrangement—it would allow them to avoid even more bloodshed, and they could negotiate a role for themselves in the Syrian government. Iran, an Assad ally, might also accept an agreement because it would reverse Turkey’s advance east. Such a settlement wouldn’t end the Syrian war, but it would help temper the conflict in Afrin.

It remains unclear whether the pro-regime forces that were deployed to Afrin have made much progress. Turkey said it halted their advance by shelling them as they entered the province, promising to engage directly if the fighters helped defend the YPG.

Fierce Bombardment

Meanwhile, over the weekend, some 600 special forces from the Free Syrian Army, which Turkey supports, were sent to Afrin, as a probable response to the deployment of pro-regime forces. This came at roughly the same time as a UN Security Council resolution was unanimously passed calling for a 30-day cease-fire across all theaters in Syria. Turkey supported the measure but said that the resolution would not affect its operations in Afrin.

Farther south, an area east of Damascus known as Eastern Ghouta underwent some of the fiercest bombing of the entire Syrian civil war. Reports estimate that more than 500 people were killed in just a few days. Syrian army commanders have said that the bombing campaign will precede a ground offensive meant to retake the pocket of rebel resistance, which has held out in Eastern Ghouta for several years despite the Syrian army maintaining a siege and blockade of most food and aid.

The regime’s behavior in Eastern Ghouta serves two strategic purposes. First, it eliminates the risk posed by rebel-held territory on the outskirts of the country’s capital. Second, it eliminates the risk quickly so that Assad can concentrate his forces to the north, adding to the defensive capabilities that the regime can deploy to block and prevent Turkey from moving too far inland.

The Geopolitics of the American President

The Geopolitics of the American President