What do the Turkish lira, the Iranian rial, the Russian ruble, the Indian rupee, the Argentine peso, the Chilean peso, the Chinese yuan and the South African rand all have in common? They’ve all declined steadily this year, and some have depreciated dramatically in the past two weeks alone. But this isn’t the whole story. The whole story is that each of these countries is sitting on a ticking time bomb of U.S. dollar-denominated debt.

This story has been long in the making. In the 1990s, many countries began to accumulate large amounts of debt denominated in U.S. dollars. It was an effective way to kick-start economic activity, and so long as their own currencies remained relatively strong against the dollar, it was fairly risk free. From 1990 to 2000, dollar-denominated debt tripled from $642 billion to $2.17 trillion.

The problem may now be coming to a head. Dollar-denominated debt has ballooned. In its latest quarterly report, the Bank of International Settlements found that U.S. denominated debt to non-bank borrowers reached $11.5 trillion in March 2018 – the highest recorded total in the 55 years the bank has been tracking it. Meanwhile, the dollar has strengthened amid a tepid global recovery from the 2008 financial crisis. As the currencies of indebted countries weaken against the dollar, it is becoming harder for some countries to pay their debts. This could be a bubble waiting to pop, especially if vulnerable countries don’t have the monetary policy options to protect themselves.

Turkey Isn’t Alone

Such was the case for Turkey, which is particularly susceptible to the vagaries of currency depreciation. The value of the lira had been declining for some time, but it dropped dramatically late last week. At nearly $200 billion, almost 50 percent of Turkey’s gross external debt is denominated in dollars. (Turkey’s General Directorate of Public Finance, which, unlike BIS, accounts for financial borrowers, puts that figure at nearly 60 percent.) The situation became progressively more dire through a combination of political uncertainty, unorthodox monetary policy and, most important, U.S. interest rate hikes. Turkey’s dollar-denominated debt is now almost twice as much as its total foreign reserves.

But Turkey isn’t alone. A number of emerging market currencies that were already down on the year nosedived as the news of the lira’s demise began to circulate. The starkest decline was the Argentine peso, whose value against the dollar dropped 9.5 percent in just a week, and the South African rand, which fell roughly 8 percent. Other currencies have been affected too – the Chilean peso, for example, has fallen 3.4 percent in the past week, while the Indian rupee hit a record low on the dollar during trading on Aug. 14.

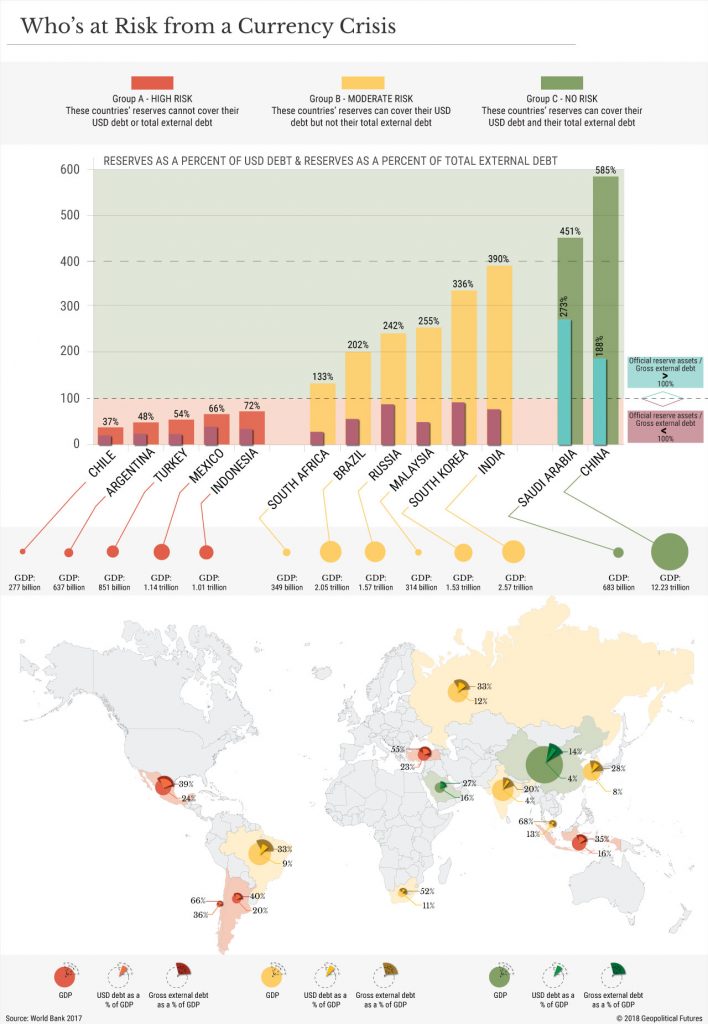

What these countries have in common is that they are all on a 13-country list released by the Bank of International Settlements. Together, they constitute 62 percent of all dollar-denominated debt held by emerging market economies. Turkey was one of the most vulnerable on the list, but there are four other countries facing similar challenges: Argentina, Mexico, Chile and Indonesia. Argentina’s peso is already in free fall. The government announced on Tuesday that it would sell $500 million worth of reserves and raise interest rates to stop the peso’s fall.

Then there is Mexico, which, at $271 billion, holds more dollar-denominated debt than any other country on the list except China. This far exceeds Mexico’s official reserves. As with Turkey, dollar-denominated debt is a disproportionately large share of Mexico’s gross external debt, at roughly 60 percent. (For perspective, Mexico’s gross external debt to GDP is 39 percent, so the dollar’s influence over Mexico is particularly strong.) So far, the Mexican peso has held steady; it is slightly up on the year, and down just 0.3 percent in the past week. But if the Mexican peso begins to weaken on the back of tougher-than-expected NAFTA negotiations, political instability surrounding the new president or any other contingency, Mexico could be as bad off as Turkey is now.

The story is similar for Indonesia and Chile. Of the two, Indonesia is in slightly better shape. Its gross external debt is 35 percent of GDP, and 47 percent of that is denominated in dollars. But Indonesia doesn’t have a lot of reserves, and its currency has been showing signs of weakness, down almost 10 percent against the dollar this year. Chile’s percentage of dollar-denominated debt as a proportion to GDP is the highest of all BIS reporting countries – a whopping 36 percent. Chile’s gross external debt-to-GDP ratio is 66 percent. Most concerning, however, is that Chilean reserves totaled just $37 billion in June 2018, equal to about a third of its total dollar-denominated debt of $100 billion.

Different Problems

Though these countries are the most vulnerable to a stronger dollar, six others – Brazil, India, South Korea, Malaysia, Russia and South Africa – face different but related problems. South Africa, for example, isn’t particularly indebted. The government insists it won’t intervene to stop the rand’s decline, but that’s only because it doesn’t have nearly enough reserves to cover what debt it has. (Its $50.6 billion in reserves could pay off just 28 percent of gross external debt.)

The five other countries are in a better position when it comes to reserves. Though they hold larger amounts of dollar-denominated debt, they have plenty of reserves. The issue for these countries is larger external debt. A strong U.S. dollar won’t cripple these economies, but it could put enough pressure on them to compel monetary intervention.

Particularly well insulated from the budding currency crisis are China and Saudi Arabia. China’s currency has been under pressure in recent weeks, but so far China has chosen not to let the yuan slide too far. China holds $548 billion in dollar-denominated debt, but that makes up just 4 percent of China’s GDP, and China’s gross external debt to GDP is 14 percent – the lowest of the countries on this list. China also has a war chest of $3.2 trillion in foreign reserves that it can deploy.

Saudi Arabia has the benefit of ample foreign reserves too – and it will certainly have to use them. The Saudi rial is pegged to the dollar. This offers stability but comes at a price: Saudi Arabia has to buy and sell reserves to maintain the peg. Though Saudi Arabia has more than enough money to play around with, it has less than it once did. Indeed, it’s been burning through its reserves in recent years – $233 billion since 2014 – to fund its adventurism abroad and its government deficit. Riyadh has no shortage of problems it needs to solve. But the currency crisis likely isn’t one of them.

This is hardly an exhaustive list. The economies surveyed by BIS make up just 37 percent of total dollar-denominated debt held worldwide, meaning there is another $7.2 trillion in such debt in the global system to account for. What started in Turkey may well spread to other countries excluded from the BIS report. Again, Turkey was uniquely susceptible to this sort of thing. The country has low savings rates and high inflation rates and all but refused to make the politically unpopular decision to raise interest rates before it was too late. We will investigate whether the other countries identified in the BIS report have similar structural problems that could aggravate their exposure to a stronger U.S. dollar.

As for Turkey, most of the polices that created its economic problems are still in place, even though investors were somewhat encouraged by the central bank’s promise to pump as much liquidity into the system as necessary. Turkey’s economy will get worse before it gets better. The more important question now is whether that will spread to other vulnerable countries. The most worrying at this point are Argentina, Mexico, Indonesia and Chile. It’s too early to call a full-blown global financial crisis, but it’s not too early to begin to consider whether what’s happening in Turkey is simply a Turkish matter.