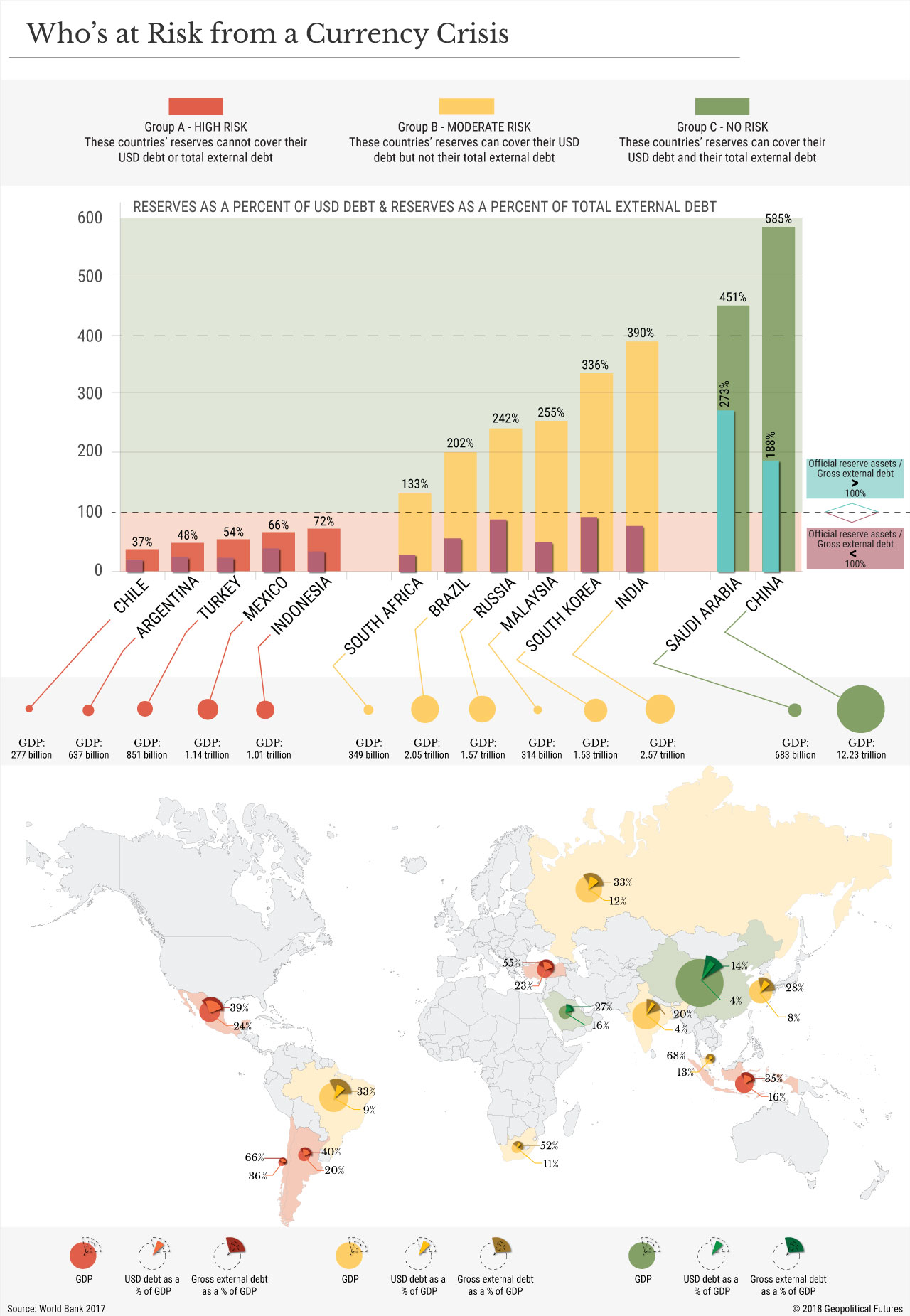

What do the Turkish lira, the Iranian rial, the Russian ruble, the Indian rupee, the Argentine peso, the Chilean peso, the Chinese yuan and the South African rand all have in common? They’ve all declined steadily this year, and some have depreciated dramatically in the past two weeks alone. The Turkish lira, for example, dropped steeply late last week. At nearly $200 billion, almost 50 percent of Turkey’s gross external debt is denominated in dollars. (Turkey’s General Directorate of Public Finance, which, unlike BIS, accounts for financial borrowers, puts that figure at nearly 60 percent.) But this isn’t the whole story. The whole story is that each of these countries is sitting on a ticking time bomb of U.S. dollar-denominated debt.

This story has been long in the making. In the 1990s, many countries began to accumulate large amounts of debt denominated in U.S. dollars. It was an effective way to kick-start economic activity, and so long as their own currencies remained relatively strong against the dollar, it was fairly risk free. From 1990 to 2000, dollar-denominated debt tripled from $642 billion to $2.17 trillion.

The problem may now be coming to a head. Dollar-denominated debt has ballooned. In its latest quarterly report, the Bank of International Settlements found that U.S. denominated debt to non-bank borrowers reached $11.5 trillion in March 2018 – the highest recorded total in the 55 years the bank has been tracking it. Meanwhile, the dollar has strengthened amid a tepid global recovery from the 2008 financial crisis. As the currencies of indebted countries weaken against the dollar, it is becoming harder for some countries to pay their debts. This could be a bubble waiting to pop, especially if vulnerable countries don’t have the monetary policy options to protect themselves.