By Allison Fedirka

Corruption allegations are nothing new in South America. But the conviction of former Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva on corruption and money laundering charges has made headlines worldwide. Many believe that elite politicians and members of the business community who consider themselves above the law are finally being served justice. But this ignores some of the challenges associated with these anti-corruption campaigns. As the Brazilian case demonstrates, they can have unintended and far-reaching consequences on a country’s economic and political systems, as well as those of its neighbors.

The Scandal

Silva’s conviction is part of “Operation Car Wash,” a sprawling investigation that started in March 2014. It was initially an investigation into a small money-laundering scheme involving gas stations, but in 2015 it expanded to include allegations of corruption involving Brazil’s state-owned oil company, many of Brazil’s largest construction and engineering businesses and dozens of high-level elected officials from multiple political parties. With nearly 100 people convicted so far, it’s now the largest corruption scandal in South America.

Silva was previously implicated in another scandal known as Mensalao. That scandal broke in 2005, while Silva was in office, when it was discovered that Silva’s Workers Party paid members of Congress to vote in favor of legislation proposed by the government. At the time, it was one of the largest political scandals the country had seen, and though Silva was at the center of it, he was never convicted of a crime.

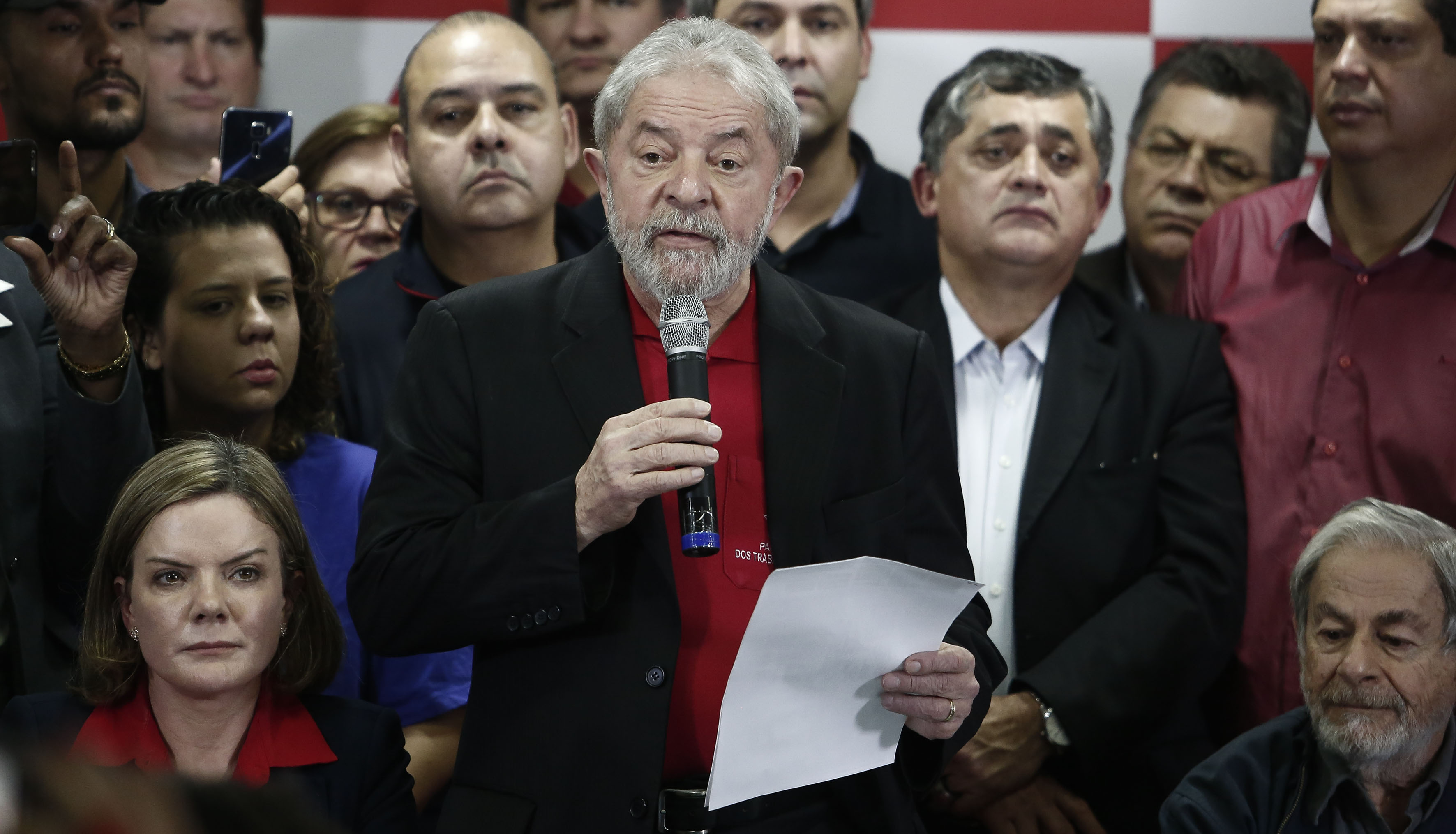

Former Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva speaks during a press conference in Sao Paulo, Brazil, July 13, 2017. MIGUEL SCHINCARIOL/AFP/Getty Images

Silva’s conviction in “Operation Car Wash,” as well as the impeachment of former President Dilma Rousseff and the corruption allegations against current President Michel Temer, suggest that the political elite are no longer untouchable. And we’re seeing this trend gaining ground in the rest of South America too. The justice system, especially in Brazil, has been increasingly proactive in tackling the problem throughout the continent.

But anti-corruption campaigns face one major problem: an expanding network of guilty parties. Corruption schemes usually involve a vast network of people who can benefit from collaborating in illicit activities. The political elite usually get the most attention, but the business elite have been just as involved.

Once the prosecution realized the seriousness of the case and the extent of the corruption, it proceeded with caution. Without a calculated approach – which was applied as the case went on – this investigation could have unhinged Brazilian politics and the country’s economy (even more than it already has). Even the judge in Silva’s case refrained from throwing Silva in jail immediately, saying he wanted to exercise caution and avoid any shock to the country that could come from sending a former president to jail. Instead, Silva will remain free throughout the appeals process and won’t be sent to prison until all legal recourses have been exhausted. Silva can even run for president again in 2018 if his case remains open until then. Some may find that surprising, but for most people in South America, it’s par for the course.

The prosecution’s cautious but deliberate strategy has three key components. First, it has used plea bargains (also known as leniency agreements) to work its way through the network of corruption. Those implicated in the scandal receive lighter sentences in exchange for providing new leads in the case. These agreements have been generously used in Brazil in an attempt to fully discover the extent of this particular corruption network. Second, the investigation has pursued legal charges against individuals rather than punishing business entities. The scandal involved many major companies; going after them could have paralyzed the economy. Targeting the individuals at the companies instead was an acceptable substitute. Last, prosecutors have used discretion in considering which cases to pursue in an attempt to responsibly tackle corruption and avoid creating massive new problems. For example, prosecutors have been restrained in their approach to Brazil’s state-run development bank BNDES. Corruption is widely rumored to be rampant at the bank and in the infrastructure projects it has funded throughout South America over the past decade. But targeting this bank will open a Pandora’s box, which authorities believe is better left shut.

The Implications

This may seem like just another national political scandal in Brazil, but it has geopolitical implications. Brazil is highly integrated politically and economically in the region, so this scandal has had a spillover effect. Silva’s campaign managers and strategists and other high-level elected officials in Brazil have been employed by political parties and candidates in other South American countries. Brazilian companies have also played a major role in the region’s economy, and many of Brazil’s major construction firms – including Odebrecht, OAS, Camargo Correa, Quieroz Galvao – were involved in this scandal. These same companies led and invested billions of dollars in critical infrastructure projects throughout South America. As a result, this corruption scandal has spread to other South American countries.

High-profile politicians and businesses in a dozen countries, many in South America, now face major anti-corruption investigations because of their involvement with Brazilian companies (especially Odebrecht and OAS) and political figures implicated in the scandal. Many of the allegations against those companies and politicians are similar to the allegations in the Brazilian case – preferential bidding, overpaying for contracts and using public money to fund election campaigns. Figures linked to these cases include Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos, Venezuelan opposition leader Henrique Capriles, Chilean President Michelle Bachelet and former Peruvian presidents Alejandro Toledo and Ollanta Humala. There have also been suggestions that people connected to Peruvian President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski and Argentine President Mauricio Macri could be tied to the case as well. Other countries that have been affected by the spillover include Mexico, Mozambique, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala and Panama. And though it has not yet spread to Cuba, Havana could very well be the next to be implicated. Odebrecht has spent more than $1 billion on developing the port of Mariel and other infrastructure projects. Many governments have suspended projects linked to the scandal, canceled contracts or temporarily blocked companies under suspicion from getting involved any further in their countries to distance themselves from the allegations.

What started as a small money-laundering investigation has destabilized the Brazilian political system and depressed the Brazilian economy, and it now threatens to do the same to half a dozen other South American countries. Each of these countries now must decide how to respond to the allegations. Brazil’s economy has managed to survive the fallout from the corruption scandal and is now slowly recovering. The same cannot yet be said for the political system. The “Operation Car Wash” case in Brazil has demonstrated that anti-corruption campaigns can have far-reaching consequences even outside the country in which the campaigns were initiated. This won’t stop corruption campaigners from pursuing their goals, but it will serve as a cautionary tale for future investigations.