Originally produced on March 26, 2018 for Mauldin Economics, LLC

By George Friedman and Jacob L. Shapiro

A few weeks before Germany’s federal elections last September, Chancellor Angela Merkel accused the Polish government of undermining the foundations of the European Union with its controversial constitutional reforms. This week, a much weakened and far friendlier Merkel traveled to Warsaw to meet with the Polish prime minister and president in an attempt to woo Poland’s support for Franco-German efforts to reform that very same European Union. The foundations of the EU are still the topic of conversation, but the particulars are not about what Poland is doing to undermine them but about how crucial Poland is to their defense.

A Different Tone

Merkel did not emerge from elections unscathed, but she emerged nonetheless. Now that she has, she must throw the full weight of her limited powers into halting the EU’s slow decline into irrelevance. No country is more dependent on the EU than Germany, and the EU is in trouble. The UK is leaving. France would like to rewind history and go back to when it dominated the EU. Italy is a circus. Eastern Europe has defied the EU and is no worse for wear; in fact, it does not have the migrant integration issues that the more generous Germans are facing. And now a chorus of anti-EU voices, represented by the nationalist Alternative for Germany (AfD), is rising in Germany itself, arguing that perhaps Berlin would be better off cashing in on its massive trade surplus and going it alone.

Merkel has one thing going for her. The European economy has defied the odds and continued to improve, with better-than-expected growth figures across the bloc. Growth has been higher in Eastern Europe, but even in Germany, it has exceeded government estimates. This is not to say that the European economy is healthy, but right now, the situation is stable—and if the EU is to make a change, now is the time. Once a crisis comes, it is usually too late to fix it.

Germany’s missteps with Greece’s 2009 sovereign debt crisis and the migrant issue have damaged its credibility in the EU, but Germany remains powerful. It is, after all, the economic behemoth upon which the EU’s prosperity (and peace) has been built. Germany’s dependence on exports is its Achilles’ heel, but Germany depends on exports only because it has profited from them so greatly. And much of Europe has shared in those profits.

The supply chain for German goods is inextricable from the economies of Eastern European countries. For now, that means the economic fate of Eastern Europe remains tied to Germany’s own fate. As for the rest of Europe, it is easy to forget that Greece was not the only country to gorge itself on debt to buy new-fangled German goods. Greece was just the worst offender; it was also the European country weak enough to be used as Germany’s scapegoat.

Power Sharing

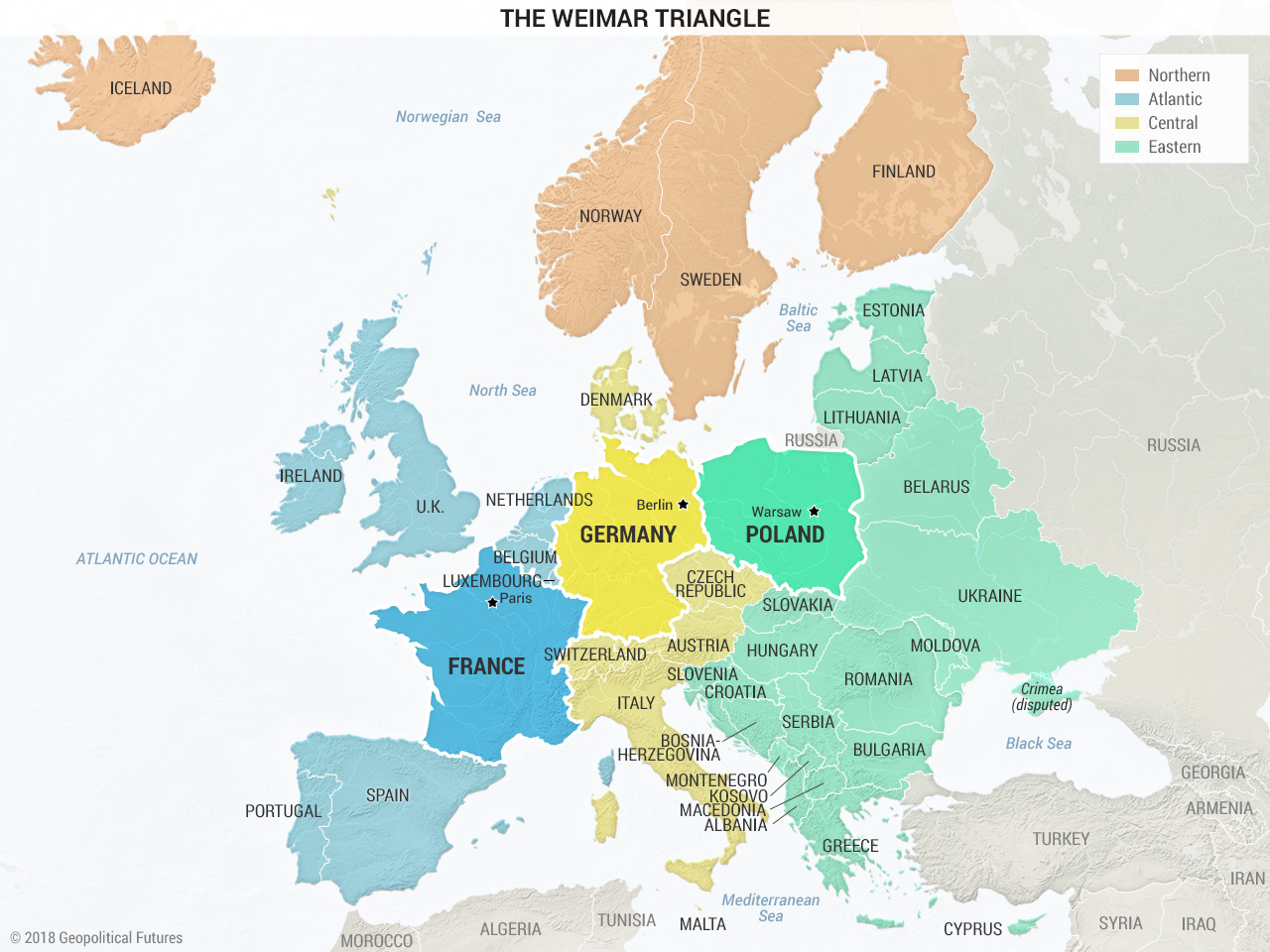

The problem facing Merkel is that Germany cannot transform the EU alone, and her list of allies has grown thin. As long as Emmanuel Macron governs France, Merkel has a willing partner in Paris, but much of Macron’s domestic support came from protest votes against a national pariah, not from genuine pro-EU sentiment in France. The realities of politics are already descending upon Macron, whose domestic support is declining. And to the east, Germany has not only failed to find a willing partner, it has pushed its would-be partners away for fear of diluting German power inside the EU’s vast and laborious bureaucracy. Beggars can’t be choosers, however, so Germany must work with what it has. Enter “the Weimar Triangle.”

Originally a grouping of the foreign ministers of Germany, France, and Poland, the Weimar Triangle was founded after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Now, it is being touted by Germany as a salve for the EU’s problems. The grouping has not met since 2015, when Poland’s current government came to power—but not because Poland wasn’t interested. Poland had previously raised the possibility of meeting with Germany and France in the Weimar format.

Now it appears Germany is willing to let bygones be bygones and assemble the group once more. Germany’s foreign minister made explicit mention of the Weimar Triangle during his visit to Poland, identifying its resurrection as integral to fixing Europe’s problems. In other words, Germany needs Poland’s help if it isn’t already too late.

A True Union of Europe

It remains to be seen whether this is just talk, or whether Germany is prepared to compromise. Poland is not staunchly anti-EU—in fact, most polls show the population supports the bloc. But more than that, Poland is pragmatic, and it might be open to German proposals if they are accompanied by real concessions. After all, Poland derives many benefits from EU membership.

Besides the economic benefits that come from being a part of the German supply chain, Poland receives much-needed investment funds from the EU. In 2016, the latest year for which full data is available, Poland received 10.6 billion euros ($13.1 billion) from the EU budget while contributing only 3.5 billion euros. Poland also values EU support against Russia, both in military and economic terms (like the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline). Whatever Poland’s long-term interests, in the short term, Poland would like to be part of the EU if it is truly a European union.

What Poland won’t tolerate is German economic colonialism masquerading as a union of Europe, a bloc in which Germany gets to set the rules and threaten to take away funds from anyone who doesn’t play the way it wants (which has been Germany’s position on Poland during the past three years). The question then becomes: Is Merkel willing to share power with Paris and Warsaw, and can she survive politically if she does?

If talk of the Weimar Triangle is not accompanied by concessions that allow Poland more of a say in European decisions, this diplomatic overture will be short-lived. But if Germany is really talking about sharing power, Poland would likely be open to using its position as the largest country in Eastern Europe to bring some of the current EU renegades, like Hungary, into the fold. It may even be willing to tolerate Berlin’s self-righteous criticism of its government, as long as the criticism is rhetorical and not used to hold the Polish economy hostage.

The Weimar Triangle is a seductive idea, and it has some geopolitical logic behind it. It would unite the three most important countries in the three regions of continental Europe—western, central, and eastern—into a powerful force for EU reforms and political change. And if the EU is to survive, that change is badly needed.

These reforms can proceed in two basic directions: either the EU can be granted far more substantial powers, or its powers can be stripped away, which would end the half-cocked experiment of European integration and preserve the all-important free-trade zone. The current French proposal tries to do both, creating two tracks within the EU—one integrated into a more unified, centralized system, and another that is content with participating in the free-trade zone—but no one is listening. The devil is in the details, and once you start examining the details, you begin to concur with Merkel’s pre-election sentiments: Berlin and Warsaw want different things.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East