By Jacob L. Shapiro

Imagine a country – a Muslim majority country, no less – that viewed the spread of jihadism as an existential threat, a threat so serious that it was willing to sacrifice its own people to defeat it. Assume that this country, with its large population, robust military and plentiful natural resources, was strong enough to keep the jihadists at bay. Assume, too, that this country was located in the heart of the Muslim world, ideally situated to project power into the Caucasus, the Middle East, Central Asia and South Asia – all of which are experiencing varying degrees of instability. Imagine finally that this country was also once a U.S. ally – a cornerstone of U.S. containment strategy against the Soviet Union during the Cold War – and could be again.

If it isn’t obvious yet, this is not an imaginary country. It is the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Iran has confounded generations of U.S. policymakers. When World War II gave way to the Cold War, the U.S. understood just how strategically important Iran was. In 1953, worried that Iran’s newly elected prime minister, Mohammed Mossadegh, would ally with the Soviet Union, Washington (and London) supported a military coup that replaced Mossadegh with a puppet government that came to be seen by many Iranian people as illegitimate. It would take some time for the Iranians to rise up against it, but rise they did in 1979. A theocratic government has ruled ever since, and U.S.-Iranian relations have been defined by mutual hostility, marked by proxy wars, menacing threats and mutual recriminations.

Losing Iran was a major strategic defeat for the United States. We know now that the Soviet Union was in decline and would soon implode. But at the time, it meant the balance of power in the Middle East was suddenly up for grabs. The United States therefore moved quickly to support neighboring Iraq, sharing intelligence and economic aid with Baghdad during the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988). The U.S. also began looking for ways to undermine the legitimacy of the new regime.

In other words, the United States never really cared about the ideological inclinations of the new governments in Tehran or Baghdad; it cared only about their utility in countering the Soviets. Moscow was the main adversary, and U.S. foreign policy had to be governed by power politics, not ideological preference. Saudi Arabia, for example, was both undemocratic and religiously radical, but it had oil and was willing to exclusively take dollars for that oil in return for U.S. protection. Egypt was run by a military dictatorship, but when it was ready to leave the Soviet camp and sign a peace treaty with Israel, the U.S. rewarded its loyalty by providing Cairo billions of dollars in military aid annually. Turkey, one of Washington’s most important Cold War allies, underwent several military coups, but democracy in Turkey was less important to the U.S. than keeping the country, and its strategic location on the Bosporus, aligned with the West.

Delusions

And then suddenly, everything changed. Twelve years after the Iranian Revolution and three years after the bloody Iran-Iraq War ended in a stalemate, the Soviet Union collapsed. Containing the Soviet Union had been the primary objective of U.S. foreign policy for nearly 50 years, and in 1991, that objective had been achieved. The shift was as jarring strategically as it was intellectually. The Cold War pitted two would-be superpowers against each other, but it was also an ideological conflict. The Soviet Union was a communist regime, and it considered itself the vanguard of the global revolution Marx and Lenin had envisioned. The U.S. was a capitalist country, one that emphasized democracy and the sanctity of individual choice. When the Cold War ended, it didn’t just mean an end to hostilities – it meant an end to a much broader ideological conflict that had been raging for decades.

Dizzy from victory, the Western world indulged itself with optimistic ideas about the future that just a few years earlier had been unthinkable. In Europe, a Cold War alignment of Western European states now became enlarged to continental proportions. The Maastricht treaty was signed the year after the Soviet Union collapsed, and the European Union came into being the year after that. The EU was a noble dream, one which held that the only thing necessary for continued peace in Europe was a shared prosperity with the countries that had been trapped behind the Iron Curtain.

In some ways, though, the United States was just as delusional as Europe. The U.S. did not try to make a unified political entity out of North America. But with the end of history now declared, many Americans believed that their values should be everyone’s values and that the government in Washington had an obligation to impose them on others. It was a sentiment embodied best by a mode of thought we now call neoconservatism. If the European Union was Europe’s heroic delusion, neoconservatism became the American equivalent.

Neoconservativism had its roots not in the spread of U.S. values around the world, but in pushing for a more vigorous U.S. offensive against the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1980s. But when the world order changed after 1991, so too did the way the U.S. engaged the world. The first laboratory for this change was the Clinton administration, which was generally characterized by liberal internationalism – a practice that, like neoconservatism, advocates the spread of American values around the world.

They disagreed markedly on how this should be done. Neoconservatives distrusted international institutions; liberal internationalists supported them. The United Nations, the liberal internationalists argued, could become a real force for change, unencumbered as it now was by the restrictions of Cold War politics. And so the U.S. hailed the creation of the EU, expanded the NATO alliance, and intervened in places like Somalia and the Balkans for ideological, not strategic, reasons.

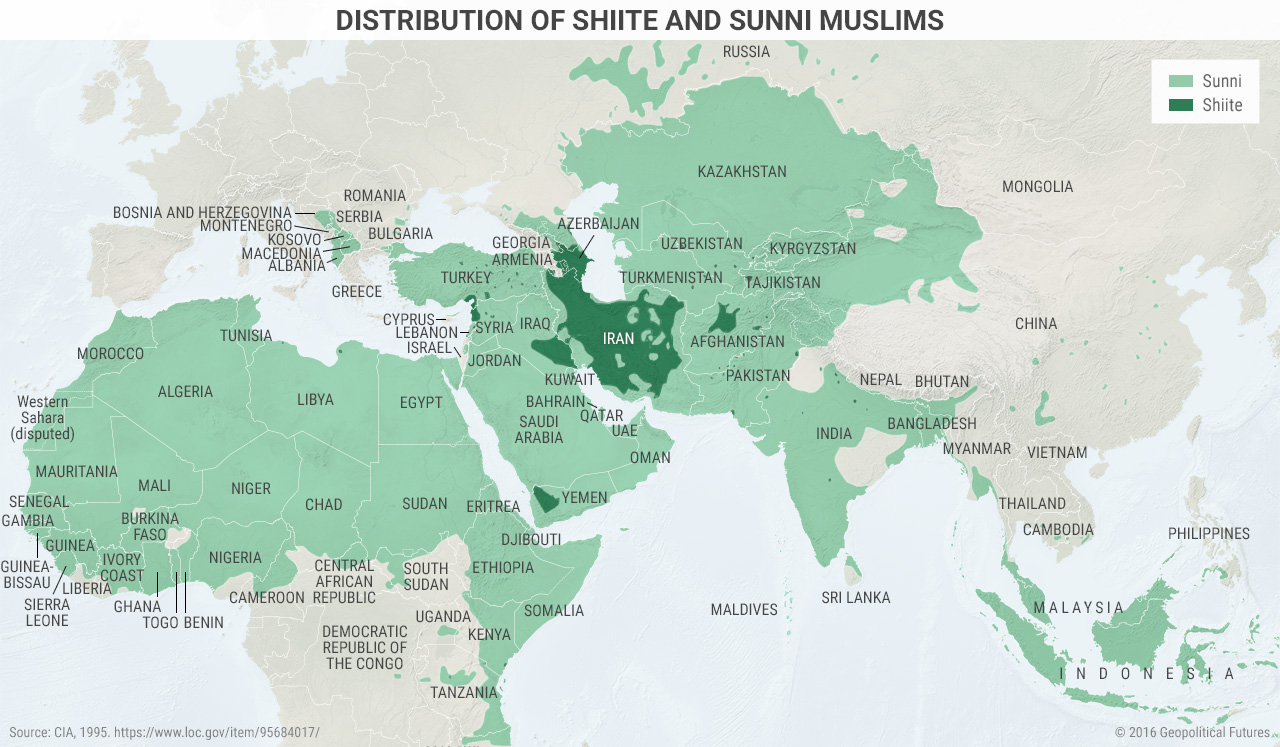

When the administration of George W. Bush took office, the neoconservatives got their chance to apply their principles on a global scale. Newly empowered and free of the constraints the competition with the Soviet Union had imposed on American foreign policy, they had freedom to think more ambitiously than they had had before. The goal was no longer to defeat the Soviet Union but how best to remake the world in the United States’ image. The neoconservatives came to believe that the spread of U.S. values was not just desirable: It was essential to U.S. national interests. This kind of ideological crusade is more effective against ideological enemies, so the U.S. fixated on ideologues – radical Islam (applied indiscriminately to both Sunni and Shiite varieties) and the last vestiges of communism (North Korea).

What the U.S. Needs

This is the historical context in which U.S. President Donald Trump has appointed John Bolton – one of the most aggressive neoconservatives of the Bush era – as his national security adviser. The move sends mixed signals, to say the least. Trump campaigned on the belief that the Iraq War was a terrible mistake; Bolton is one of the war’s strongest advocates. Trump also campaigned on a foreign policy of “America first.” Bolton is also about putting America first – the difference is that Bolton thinks in terms of putting America first everywhere in the world, and not just at home. Unsurprisingly, his appointment has caused confusion and apprehension for U.S. allies and enemies alike. Take Russia. Modern Russia is not the Soviet Union – its animating principle is Russian nationalism, not proletarian revolution – and Moscow believes this is a saner basis upon which to conduct bilateral relations. It’s not particularly interested in a battle of ideas, especially Cold War-era ones that stand in the way of compromise on issues such as Syria, Ukraine and sanctions.

But perhaps no country is more worried about the developments in the Trump administration than Iran. All indications suggest Trump will abrogate the Iran deal on May 12. Whether it happens on May 12 or on some other day is immaterial; the fact is that Washington is on the verge of forfeiting a pragmatic relationship with Tehran for an openly hostile one. Superficially, this makes a certain amount of sense. The Iran nuclear deal arose out of a specific set of geopolitical circumstances. Iran recognized the rise of the Islamic State as the potentially existential threat it was, one that at best could prevent Iran from being a major player in the Middle East and, at worst, unite Sunni Arabs against it. The U.S., weary of constant war in the Muslim world, signed the deal so that Iran would do its fair share of the fighting. Iran and the U.S. needed each other. Ideology was cast aside.

The Islamic State has now been defeated, and Iran has capitalized on its successes by attempting to institutionalize its control of Iraq (the success of which remains to be seen) and by turning the Assad government in Syria into a full-fledged Iranian proxy, replete with Iranian ground forces and military bases in Syrian territory. This is hardly an ideal situation for the United States. The U.S. certainly does not want to see what it routinely calls the world’s largest sponsor of state terror extend its reach all the way to the Mediterranean, as it threatens to now.

What the U.S. needs more than anything in the Middle East is a stable balance of power. Turkey, which is becoming increasingly independent of the U.S. in its foreign policy decisions, is also emerging as a potential regional hegemon, and if the U.S. were thinking in strictly strategic terms, it might not approach the Iran issue in absolute terms.

Consider this. A major struggle for political power is taking place in Iran. The protests earlier this year are proof enough of that. Hasan Rouhani’s administration agreed to fight the Islamic State and give up Iran’s nuclear pursuits, however temporarily, because it needed oil revenue and, more important, the foreign investment that has come with the deal. If Rouhani is to prevent Iranian politics from becoming completely dominated by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, he needs the economy to continue to grow – which won’t happen without foreign investment. This is why Rouhani has said Iran may remain a party to the nuclear agreement even if the United States pulls out. In 2005, long before the U.S. started imposing its sanctions, the EU imported about 6 percent of its oil from Iran. By 2012, economic sanctions halted all Iranian oil imports (officially, at least). Last year, the EU imported nearly 5 percent of its oil from Iran. The government in Tehran wants to safeguard and increase those sales – which gives the international community a powerful source of leverage over the Rouhani government.

Internationally, Iran is overextended. The country is working closely with Russia, which it believes can help it achieve some of its regional goals, but Moscow has even less interest in Iran’s dominating the Middle East than Washington does (and tensions between them are already mounting). The U.S. is separated from Iran by a continent and an ocean. Russia is separated from Iran only by the Caucasus and Central Asia – both of which lie within Russia’s desired sphere of influence, and both of which are areas where centuries of Persian influence could make Iran a significant threat to Russian control. And so, at a strictly strategic level, it would make sense for the United States to try to maintain a balance of power between Turkey and Iran and to use both to push back against Russian ambitions in its much-coveted former buffer zones. Antagonizing Iran only makes Iran more aggressive and pushes it closer to Russia. Blowing up the nuclear agreement and attempting to impose new sanctions on Iran would mean convincing the EU to stop importing Iranian oil – which means the EU would have to increase its dependence even more on Russia.

The view that Iran is the primary U.S. enemy is an ideological one, a vestige of Washington’s long and complicated relationship with Iran and a Cold War victor’s rose-tinted mindset. But facts are facts. Regime change in Iran would be difficult to achieve, if not impossible, and the attempt would only buttress the most anti-American factions within Iran. A successful U.S. military campaign against Iran is nearly impossible – Iran is a veritable mountain fortress, and even if the U.S. had the desire to continue fighting wars in the Middle East, its forces are spread too thin around the world for a war that would be extremely bloody and costly. History has shown that if a country is intent on acquiring nuclear weapons, it will usually acquire them and then never use them (see: Israel, Pakistan, India). And any successful offensive action the U.S. takes against Iran ultimately benefits three main actors, none of which it is in U.S. national interests to enable: Russia, Turkey and Sunni jihadists.

The National Security Strategy released by the White House last December identified China and Russia as challengers to “American power, influence, and interests.” North Korea and Iran are the only other enemies mentioned by name for their efforts “to destabilize regions, threaten Americans, and brutalize their own people.” The U.S. cannot fight both of these battles at the same time, and history has shown the U.S. is infinitely better suited to deal with the former, not the latter. The Iran nuclear agreement issue is a sideshow – the bigger issue is whether the U.S. can find some basis for pragmatic engagement with Iran. As hard as it is to imagine now, geopolitics says the U.S., whatever the ideologies of its leaders, whether neoconservative or liberal internationalist or isolationist, will reach some kind of accommodation with Iran as it combats bigger threats on the horizon. In other words, the U.S. is about to give geopolitics a major test, and the world is anxiously awaiting the results.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this report misstated the year the Maastricht treaty was signed. It was drafted in late 1991 but was not signed until 1992. The error has been corrected on site.