By Xander Snyder

While the interests of Turkey and the U.S. in the Middle East are diverging, there are still areas of overlap where the two will find opportunities to cooperate. One of these areas is Syria’s northwest region of Afrin. On Jan. 14, a spokesman for the U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State in Syria announced that the U.S will work with the Syrian Democratic Forces to establish and train a new 30,000-strong border security force, purportedly to keep IS from regaining a foothold in the region.

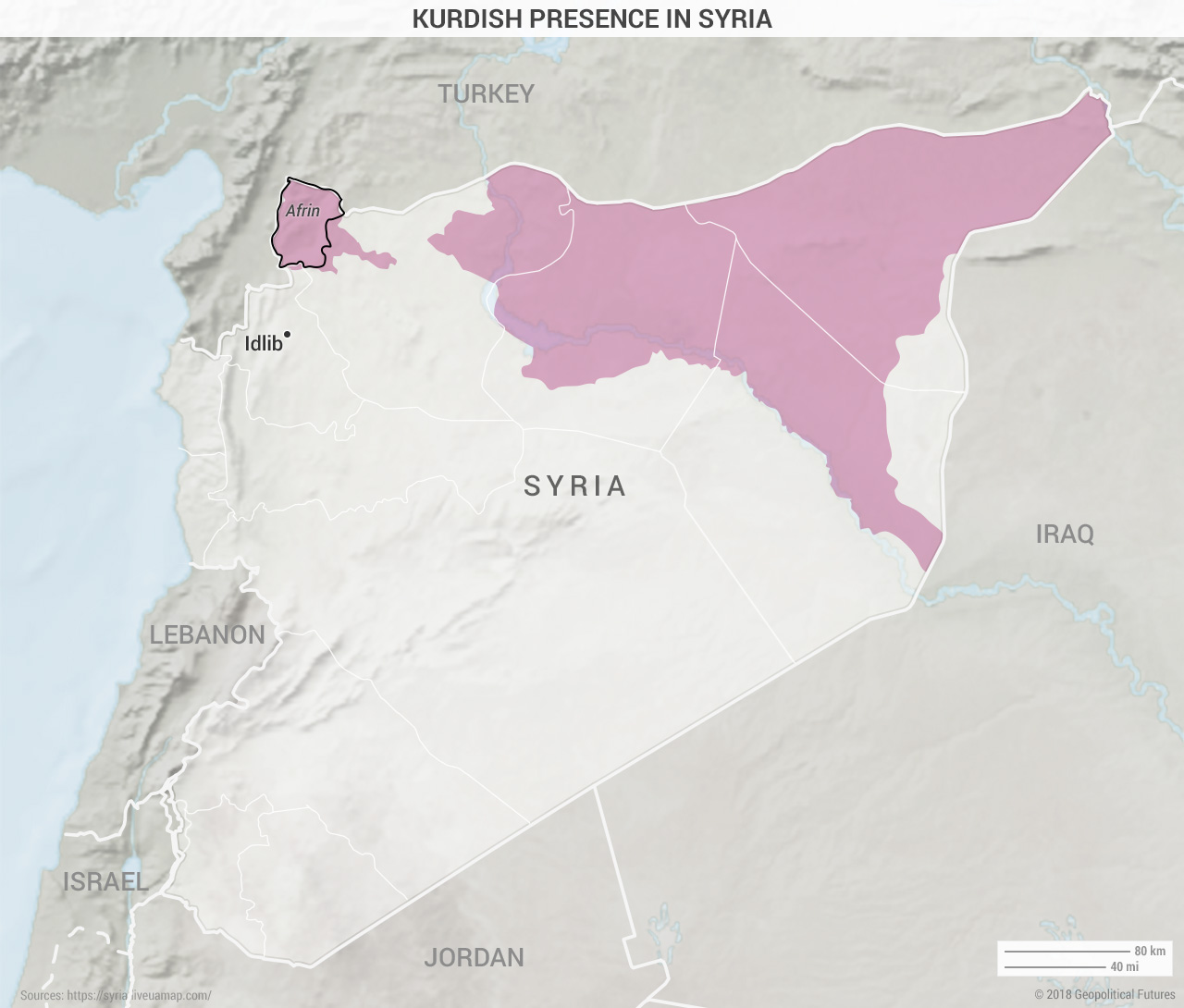

Turkey reacted to the announcement with outrage. The SDF is made up of mostly Kurdish militia forces, led by the People’s Protection Units, or YPG. While U.S. support of the Kurds has focused on maintaining a ground force to defeat IS, Turkey considers the YPG to be an arm of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, which it classifies as a terrorist organization – one that has carried out attacks in Turkey over the past three decades. (The U.S. also lists the PKK as a terrorist organization, but claims it is separate from the YPG.) Afrin poses a particular threat because it is close to Turkey’s heavily populated south-central region, where the PKK could launch attacks if it retains territorial control of Afrin.

Turkey’s response to the announcement included a threat to invade Afrin “at any moment” and crush the new “terrorist army” supported by the United States. But Turkey has been warning about an imminent attack on Afrin for the past six months. What’s different now? First, the small number of troops that Russia deployed to Afrin in the second half of 2017 to prevent fighting between Turkey and the YPG were withdrawn in December. This action supposedly came as part of Russia’s withdrawal from Syria – which to date has not happened. With Russian troops gone, so was the risk that Turkey would accidentally kill them, which could have led to direct confrontation with Russia.

The day after the U.S. announcement, however, the same spokesman made a statement that Turkey was likely to find more amenable. He said Afrin was not within the new border security force’s area of operations. This means the U.S. will not defend Afrin. While the U.S. Joint Task Force has placed this region outside of the purview of its operations, the original announcement left it unclear as to whether Afrin would be covered by the new border security forces. Now, the U.S. is effectively giving Turkey the green light to invade Afrin.

The spokesman also said that, as of now, only about 230 troops are in training for the security force. Given the United States’ history of arming coalitions in Syria, the statement about the new Kurdish army must be taken with a grain of salt. As of September 2015, the U.S. had spent several years and more than $500 million attempting to arm the moderate rebels, but apparently had armed only a handful of fighters rather than the 4,000 it was planning to arm.

U.S. Gets Ready for the Next Stage

The real reason the U.S. is building a new northern army, though, is to prepare for the next stage in the conflict, which will be dominated by two primary coalitions rather than by disparate rebel groups. On one side is the coalition of Russia, Iran and Syrian President Bashar Assad; on the other are Turkey and the Syrian National Army, a Turkish proxy group made up of former Free Syrian Army rebels and new Islamist recruits. The United States has little influence in either of these coalitions and therefore must chart a separate course if it is to maintain a presence in the Middle East.

If either coalition wins, the U.S. loses. Turkey’s success – unlikely anytime soon – would see it and its militant jihadist proxies controlling a large territory in Syria. The success of the Russia-Iran-Assad coalition would give the U.S. adversaries an overwhelmingly powerful position in the Middle East, making it difficult for Turkey to balance Iran’s position in the future by threatening Assad’s. By forming a new Kurdish-dominated force in Syria’s north, the United States is trying to create another entity – one that depends heavily on the U.S. for survival and is therefore amenable to acting in U.S. interests – as balance between the two competing blocs. The U.S. will not be willing to commit enough resources to defeat either coalition outright. Thus, a successful outcome for the U.S. is to prevent either coalition from dominating the region.

Despite the United States’ aversion to Turkey’s use of jihadist proxy groups, it does not want Assad to regain full territorial control of Syria, as this would give Iran a powerful regional posture and provide Russia with domestic accolades. Letting Turkey invade Afrin, while the U.S. expands the Kurdish fighting force in Syria’s northeast, solves this problem, even if it is at the expense of Afrin’s Kurds.

Turkey Bolsters the Border

The announcements must be seen in the context of Assad’s ongoing offensive, backed by Russian airpower, on Idlib province. Turkey, Iran and Russia last year reached a de-escalation agreement that involved a “peacekeeping” presence by all countries in Idlib. But disagreements remain over whether Turkey actually had the right to station its forces in Syria, and whether Turkey’s anti-Assad proxies counted as terrorist organizations that were fair game for Russia and Assad to attack. Turkey warned Russia and Iran to halt the offensive, and launched a counteroffensive, resulting in a number of towns being traded between the two sides over the past week. Turkey’s position in Idlib is being threatened, and it must now either act or risk being pushed out of Syria.

Following the announcement, Turkey sent nearly 50 vehicles, including armored vehicles and tanks, to the Syrian border, where it has gradually been increasing its presence since the second half of 2017. It also began shelling Kurdish positions in Afrin – this time with greater intensity than in past attacks. Also, there are some reports on Twitter – including from a BBC journalist, a Middle East analyst and a Turkish political researcher – that Turkey’s air force has been bombing Kurdish positions in Afrin. This would be the first time it has used its air force against Kurds in Afrin. (Turkey has previously used its air force against YPG positions in southeastern Syria and Iraq.) The use of air power may be an attempt by Turkey to soften defenses before a ground invasion. While it is hard to corroborate exact troop counts, reports over the past month have indicated that there may be up to 15,000-20,000 Turkish troops on the Syrian border. Turkey claims to have an additional 15,000-20,000 proxies – members of the so-called Syrian National Army – to the south of the Afrin region. To the east of Afrin, Turkey retains a residual force from its 2016 Operation Euphrates Shield. According to estimates from Daily Sabah, a Turkish pro-government newspaper that is not always the most reliable source of information, there are 8,000-10,000 fighters from the the Democratic Union Party, or PYD, a Syrian affiliate of the PKK, in Afrin.

What the U.S. Wants

The United States does not want either the Russia-Iran-Assad coalition or the Turkey-backed Syrian National Army to control too much of Syria. Turkey – an ally of the United States during the Cold War when it depended on the U.S. for military support, and when the U.S. depended on Turkey as part of its containment line against the Soviet Union – has become less reliant on the U.S. for its security. Turkey wants to pursue its own interests rather than be dictated to by the U.S., and it is strong enough now to want weaker partners that are dependent on it. Indeed, when the Turkish military first entered Idlib in October, it was escorted by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, which only a month before was an enemy of Turkey and had annihilated Ahrar al-Sham, Turkey’s prior proxy in the Idlib region. But Turkey needed to gain a foothold in Syria, and HTS was the group that, at the time, controlled large swaths of territory in the Idlib region.

Since the Islamic State’s rise in Syria, the U.S. has been urging Turkey to take a greater role on behalf of U.S. interests and clamp down on Sunni insurgent groups. Turkey remained hesitant and kept its borders porous to allow migrating IS fighters to enter Syria, since it did not want to put pressure on groups that were actively fighting Assad, Turkey’s enemy. By giving up Afrin, the U.S. may finally be getting what it wanted – a Turkey with more skin in the game and a secure presence that can continue to threaten Assad, and therefore Russia’s and Iran’s positions in the Middle East. The regional powers that intervened to defeat IS are now jostling for position in a post-IS world.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this analysis said the U.S. spent $500 million to try to arm the YPG. Washington’s efforts were, in fact, directed toward moderate Syrian rebels, not the Kurdish militia. The error has been corrected on site.