By Xander Snyder

For all the attention rightly paid to the nuclear weapons program of North Korea, any country considering a military strike against Pyongyang needs to account for its artillery. Eliminating these conventional weapons, fixated as they are on civilian populations in South Korea, is critical, since Kim Jong Un has threatened to use them to turn Seoul into a “sea of fire.” It’s enough to make its potential targets question the wisdom of war.

There’s no question that the North can strike Seoul. There are some questions, however, over just how much damage it can inflict. And the answers to these questions lie at the heart of the political exchange between South Korea, which wants to avoid war, and the United States, which is more disposed to attack. Each side is trying to convince the other that its course of action is correct. Understanding the dynamics at play requires understanding what exactly is at stake if the North, as it has long pledged to do, fires its artillery at the South.

To Bring an Enemy to Heel

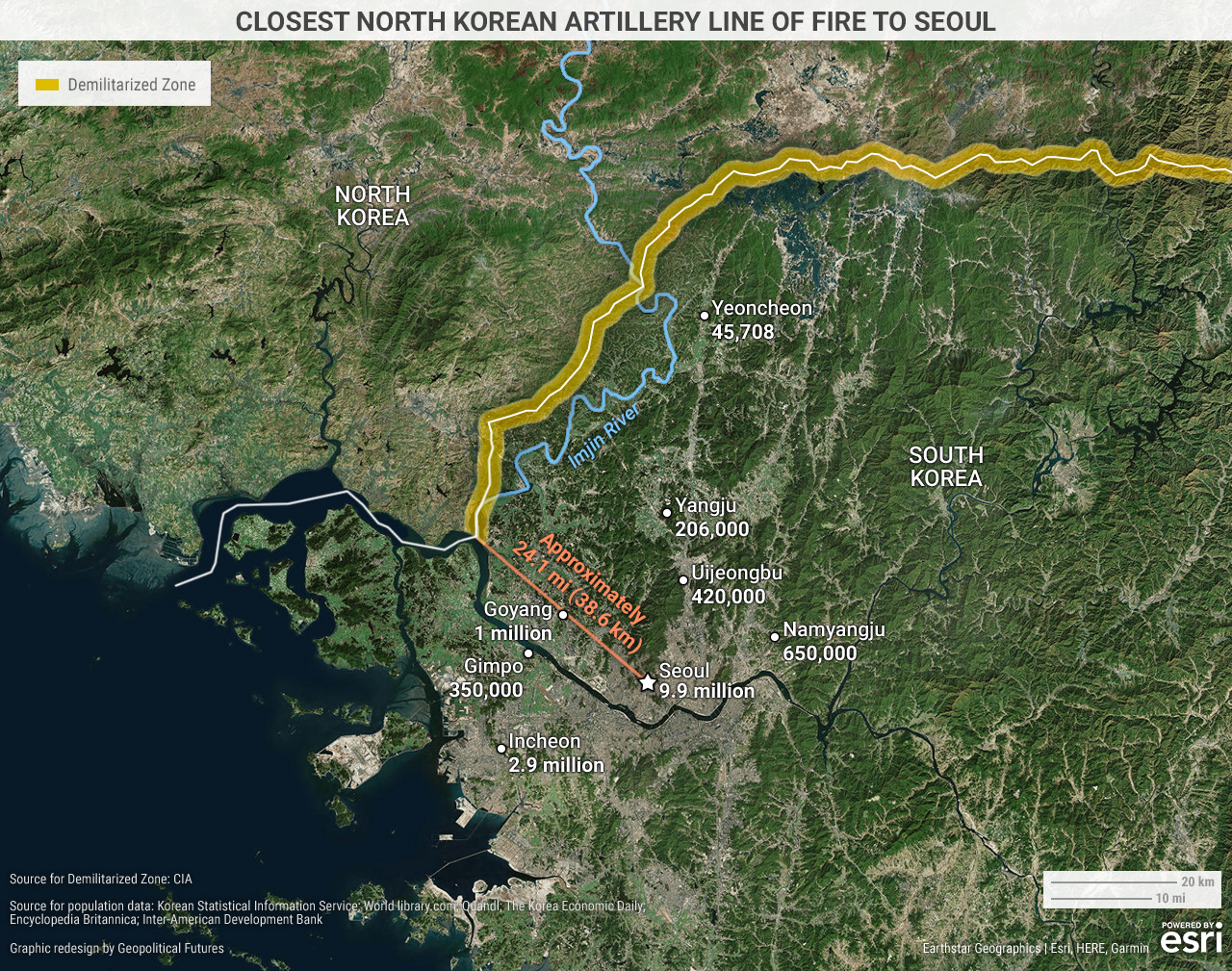

At its closest point, Seoul, the city most at risk from an artillery barrage, lies about 24 miles (39 kilometers) from the demilitarized zone. There’s a spot on the DMZ, near the southwestern part of the Imjin River, that dips just a little farther (about 15 miles) toward South Korea, a tract of flat land that would be relatively easy for an invading force to pass through. It is here that North Korea has fixed its closest artillery on the South Korean capital. But the DMZ is long, and Pyongyang can’t afford to put all its artillery in the areas in which it would do the most damage to Seoul. It must defend its entire border, so its artillery is spread more thinly than perhaps it would like.

More important than the placement of these guns, however, is the sheer number of them that can reach their target. The International Institute for Strategic Studies estimates that North Korea has more than 21,000 artillery pieces and multiple rocket launchers aimed at Seoul. But only three types of them have the range to hit Seoul: the 170 mm Koksang self-propelled guns and the 240 mm and 300 mm MRLs. The 170 mm Koksang has an effective range of approximately 25 miles (which can be boosted to approximately 50 miles with rocket-propelled shells); the 240 mm and 300 mm MRLs have a range of about 50 miles and 95 miles, respectively. It’s unclear exactly how many pieces of this artillery North Korea possesses, but estimates put the number at about 700-1,000, some of which are probably stationed closer to Pyongyang to defend the capital.

What works against North Korea is that the bigger, longer-range artillery pieces tend to fire more slowly. As soon as they begin to fire at Seoul, their positions would be revealed and would therefore be subject to U.S. and South Korean counterstrikes – and quickly, by notably superior equipment. Self-propelled artillery such as the Koksang is designed to mitigate this problem, and though it can be fired and relocated comparatively more quickly than towed artillery, it still cannot evade U.S. and South Korean targeting systems forever. The only way it could is if it is placed in fortified positions in the mountains or beneath the ground, but such positions clearly obstruct the firing path. MRLs can fire several projectiles at once, but they are easier to shoot out of the air by counter-artillery systems. Seoul might not be able to intercept all of them, but it could intercept some of them, thereby reducing the amount of damage Seoul would take. In other words, North Korea may have as many as 1,000 guns aimed at Seoul in a geographically advantageous position, but there are only so many rounds Pyongyang could fire before its guns would be destroyed or moved.

Then there is the question of strategy. If the North has only a small window of opportunity to hit Seoul, why would it waste precious time exclusively attacking civilian populations? If the North believes that winning the war requires destroying the South’s military, then it would want to strike military installations, not civilians. Based on the size of the North’s crude oil reserves, moreover, many experts believe that North Korea can wage war only for a few months at most. So if Pyongyang believes it has only a little time to attack, it might optimize its time by attacking military targets.

Still, there is more than one way to bring an enemy to heel. One strategy North Korea has likely explored is targeting South Korean infrastructure – power plants, water and sewage treatment facilities, and so on – that makes life in Seoul possible. If North Korea could strike these facilities, firing fast enough to prevent rapid repair, then it could kill many more civilians than it could by directly targeting civilians. Put simply, it is possible for Pyongyang to render parts of Seoul uninhabitable without completely leveling the city.

No Comfort

For these reasons, it seems unlikely that North Korea could turn Seoul into a “sea of fire.” The Nautilus Institute, a think tank that studies North Korea, reached a similar conclusion in a report published in 2012. Based on the range, fire rate and rate of attrition – how quickly artillery pieces will be taken out once they’ve been fired – roughly 30,000 residents of Seoul would die in the initial volley, with as many as 35,000 more dead by the end of the day and 50,000 more dead by the end of the week, according to the report.

But these figures are based on a deliberately outlandish assumption: that North Korea uses every piece of capable artillery it has to fire on cities like Seoul at optimal fire rates with a limitless supply of ammunition – with no misfires or misses. If Pyongyang attacks military installations instead, Nautilus estimates the causalities to decrease dramatically to 2,800 from the initial barrage, and most of them would be soldiers.

Notably, the report was written before North Korea tested the 300 mm MRL, so the figures could be somewhat higher. They could be higher still if Pyongyang used chemical or biological weapons on the South. The South Korean Ministry of Defense estimated that North Korea has 5,000 tons of chemical weapons, with the ability to produce up to 12,000 tons (an annualized rate of production) during wartime. It’s unclear, however, if North Korea has the capability to affix these weapons to its short-range artillery rockets. Nor is it clear what kind of biological agents Pyongyang has, but it’s safe to assume casualties would increase if it had them and chose to use them.

None of this, of course, is any comfort to Seoul. To say that tens of thousands, as opposed to millions, will die in the opening salvo of a war is to offer no solace to its residents or its leaders. It justifies Seoul’s aversion to war absolutely. The desire to avoid casualties of any magnitude is central to South Korea’s imperatives, and it’s difficult to imagine a scenario in which the United States persuades Seoul to act against its own interests.