By Phillip Orchard

For much of the past year, China has taken a somewhat softer approach to the South China Sea dispute in an effort to draw in Southeast Asian states. For example, it has opened lucrative fishing waters to foreign fleets and pledged progress on a code of conduct in the disputed waters. But this tactic was always underpinned by the yawning gap in maritime capabilities between China and its neighbors. Two developments this week merely exposed this reality, underscoring not only why China is likely to get its way on most issues in the South China Sea, but also why the success of its broader strategy remains in doubt.

On July 24, the BBC reported that Vietnam recently pulled the plug on a drilling operation in disputed waters off its southern coast because of Chinese pressure. According to the report, Hanoi told the company carrying out the drilling, a subsidiary of Spanish firm Repsol, that Beijing had threatened to attack Vietnamese bases in the Spratly Islands if the operation continued. (A second source has since confirmed the report, though Vietnam has not officially addressed the matter.) Just days earlier, the Repsol subsidiary had reportedly confirmed the existence of a major natural gas play in the block, which is located on the southwest fringe of China’s desired maritime boundary, delineated by the so-called nine-dash line.

The same day, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte announced that the Philippines and China are in talks to jointly develop oil and natural gas around Reed Bank, a contested area well within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone where drilling has been suspended since 2014. (Under international law, the Philippines has sole rights to seabed resources in these waters.) The announcement walks back earlier comments, when officials from the Philippine Department of Energy said the Philippines may reopen bidding to foreign companies by the end of the year to drill in the disputed waters – suggesting that Manila may be willing to sidestep Beijing, as it did prior to 2014. Duterte also reaffirmed an earlier claim that Chinese President Xi Jinping had threatened war when Duterte stated his intention for the Philippines to resume drilling unilaterally. Philippine Foreign Minister Alan Peter Cayetano confirmed the president’s announcement on joint drilling with China the following day during a press conference with his visiting Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi.

Joint Development, Under Duress

At this point, how far the Chinese were willing to go militarily in either case is unclear. Chinese threats regarding resource extraction in parts of the South China Sea are nothing new. The Chinese have a long history of small-scale coercive actions in the waters, typically involving harassment from their rapidly expanding coast guard or their fishing militias. We can assume that both the Philippines and Vietnam would have considered such risks acceptable before moving forward. And if both have indeed changed course, it would suggest that they think China is more willing to resort to force to stop the drilling than may have been expected.

Manila and Hanoi are both eager to find a way to access their oil and gas reserves without the Chinese. Both countries need the energy resources, and neither is inclined to delay drilling until the interminable process of resolving their territorial disputes with China fully plays out. Vietnam, for example, is set to become a net importer of crude oil in two years, while its natural gas consumption is expected to increase by some 60 percent over the next decade. In addition to the Repsol project, Vietnam recently launched a joint venture with Exxon Mobil and renewed an oil lease with Indian oil firm ONGC Videsh – both in blocks overlapping China’s nine-dash line. In the Philippines, meanwhile, Reed Bank is needed to replace the primary source currently feeding Luzon’s energy needs, the Matamata field, which is expected to run out of natural gas by the middle of the next decade.

Both countries also face considerable political and economic risks of capitulating to Chinese pressure on oil and gas development. In the case of Vietnam, for example, Repsol had already reportedly poured some $300 million into the project. If the project is indeed stopped, and not merely suspended, the decision could drive away international oil companies in the future over concerns about the above-ground risk in the disputed waters. Moreover, Hanoi is wary of having nationalist political forces push it into an unwanted confrontation with Beijing. Fresh on Hanoi’s mind is the 2014 standoff over a deep-sea oil rig that China moved into Vietnamese waters – sparking violent protests and minor skirmishes at sea and destabilizing the political landscape at senior levels in Hanoi.

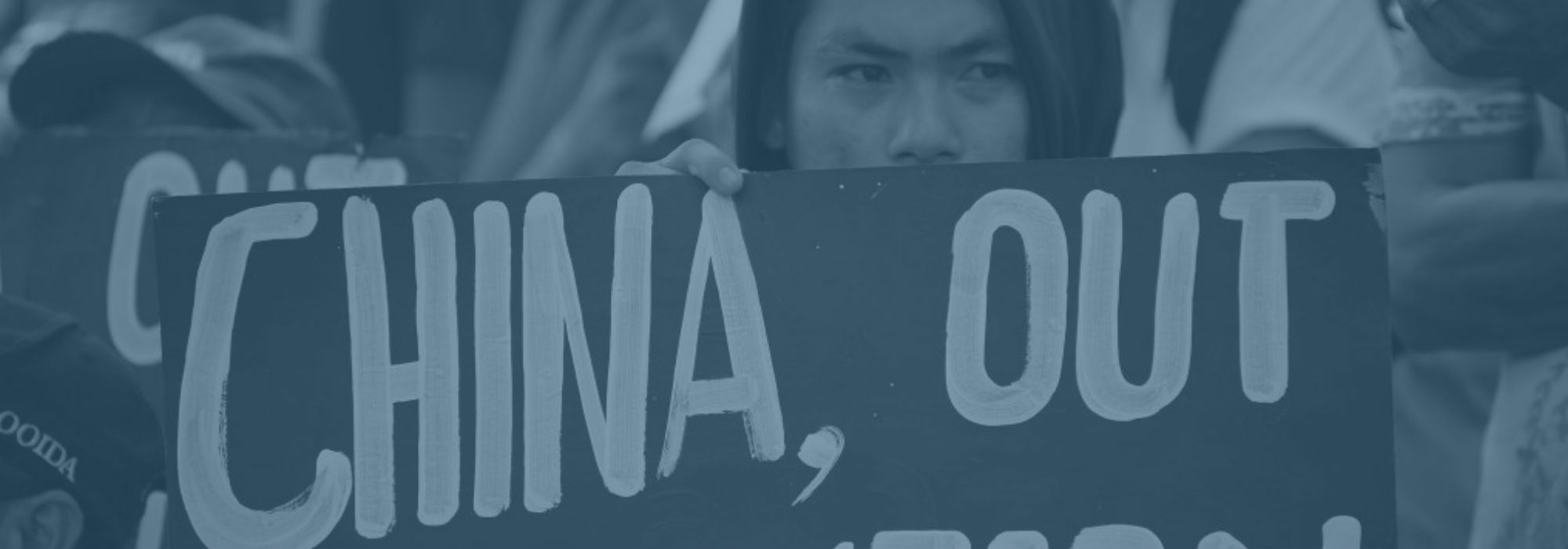

A protester holds a placard during a protest in Manila against China’s presence in disputed waters in the South China Sea on June 12, 2017. TED ALJIBE/AFP/Getty Images

A protester holds a placard during a protest in Manila against China’s presence in disputed waters in the South China Sea on June 12, 2017. TED ALJIBE/AFP/Getty Images

In the Philippines, meanwhile, Reed Bank has long been a point of contention with China, which has been pushing for joint exploration since the mid-1980s. In 2003, the Philippines abruptly broke ranks with the rest of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations to launch a joint seismic exploration venture with China’s CNOOC, eventually pulling a reluctant Vietnam on board. To the extent that the goal was to put aside the sovereignty dispute and conduct seismic exploration while sharing the cost burden, the initiative was basically successful, and it could provide a template for another try at joint development.

But any attempt at joint development with the Chinese will face legal and political hurdles. Supreme Court Senior Associate Justice Antonio Carpio, a regular Duterte foil, warned that the Philippine Constitution bars any state-state agreements on drilling in the Philippines’ EEZ. Compliance with the charter will depend on the language of whatever arrangement is reached, but it may be difficult for Manila and Beijing to strike a deal without implicitly ceding ground on the sovereignty question. Much of the Philippine defense establishment already opposes joint development with China on principle. And public support would sour if it comes to be portrayed as the political and business elite selling out Philippine sovereignty to the neighborhood bully for personal gain. The 2003 deal, for example, fell apart by 2008 amid widespread corruption allegations, including some related to Chinese investments in the country, that had been plaguing Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo for years.

It’s Not About the Oil

China is acting with much broader geopolitical imperatives in mind. For China, it’s not about the oil, or any of the known seabed resources in the waters, for that matter. (Securing access to rich fishing grounds is an imperative for China, but it is only a secondary concern.) Rather, for China, it’s primarily about pushing outward to create a buffer that shields its internal vulnerabilities and secures access to its vital seaborne trade routes south to the Indian Ocean basin and west toward North America.

China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea, encompassing some 1.4 million square miles (3.6 million square kilometers), are intentionally vague on the fringes, ostensibly leaving Beijing room to push and prod where it sees fit. But attempts at resource extraction tend to bring China’s claims into starker relief. Allowing Vietnam or the Philippines to extract mineral resources even on the very fringes of the nine-dash line, several hundred miles from the Chinese mainland, would amount to effective recognition of their sovereignty over the waters. If the Philippines and Vietnam are going to drill, from China’s perspective, they can do so only in a way that does not invalidate China’s territorial claims. Better still would be for these countries to undertake joint ventures, framing China as a source of prosperity and progress for the region while giving Beijing yet another point of leverage for use in service of its broader aims.

This strategy helps cement China’s dominance in its backyard and prevent regional states from disrupting efforts at bolstering its defenses in its near abroad, such as its militarized man-made islands in contested waters with the Philippines and Vietnam. It also underscores the limits of U.S. naval superiority, as the U.S. is reluctant to wade into minor disputes. And if Beijing succeeds in forging a joint development agreement with Manila, it would mark a breakthrough, if a mostly symbolic one, in Beijing’s ability to navigate nationalist impulses in the region (while keeping its own in check) enough to get adversaries to engage on its terms.

The Bigger Picture

But it doesn’t automatically address China’s broader geopolitical imperatives. China’s only viable strategy to ensure access to the Pacific is to reach a political accommodation with one of the nation-states that make up what’s known as the first island chain, the archipelago stretching from Indonesia to Japan. China would need to be certain that this state wouldn’t side with an outside naval power in a major conflict. Beijing’s best bet is the Philippines.

If a lasting political accommodation is the goal, then China’s apparent willingness to resort to military force on issues its neighbors hold dear like drilling may seem counterintuitive. But hard power is working for Beijing, particularly in the small doses that assert its local superiority without dragging the U.S. into the fray. After all, despite the international backlash against China’s militarization of the Spratlys, and despite last year’s international arbitration ruling that invalidated China’s sweeping territorial claims in the region, China’s position in its near abroad has only strengthened. It has received no meaningful pushback to the island building, and littoral states are increasingly divided and negotiating on Beijing’s terms.

Beijing is betting that its overwhelming superiority compared to weaker Southeast Asian states will diminish the appetite for confrontation among its southern neighbors and turn their attention toward the tangible benefits of cooperation. A lot of people are getting rich off Chinese investments in the Philippines and Vietnam, and a lot of them have considerable influence in their capitals. In other words, China is using force to declare the rules of the game, and using economic tools to make its neighbors more willing to play.

The drawback, of course, is that there is a cost to perpetual coercion, particularly when the other states have the option of partnering with stronger outside powers. And Chinese pressure will inevitably compel Southeast Asian states to keep the United States and allies like Japan no further than an arm’s length away. The 2015 agreement allowing the U.S. rotational access to Philippine military bases is a case in point. Duterte’s framing of his concession on joint development with Beijing as being done under threat of war may reduce the possibility of a nationalist backlash against him in the Philippines, but it also makes the Philippine public more distrustful of the Chinese and more likely to support a stronger alliance with the West. It hardly fits Wang Yi’s June 25 depiction of China as the Philippines’ “good brother.”

Thus, routinely flexing its muscles in its near abroad is in many ways Beijing’s only choice. Any political accommodation with Manila would be fluid and subject to shifts in Philippine political moods, and expelling the United States from the region is a long-term project, at best. China cannot outsource the task of securing its backyard to its neighbors, nor trust that they will reject all other suitors. So China is building out its buffer bit by bit, in part by demonstrating a willingness to go to the mat over issues large or small.