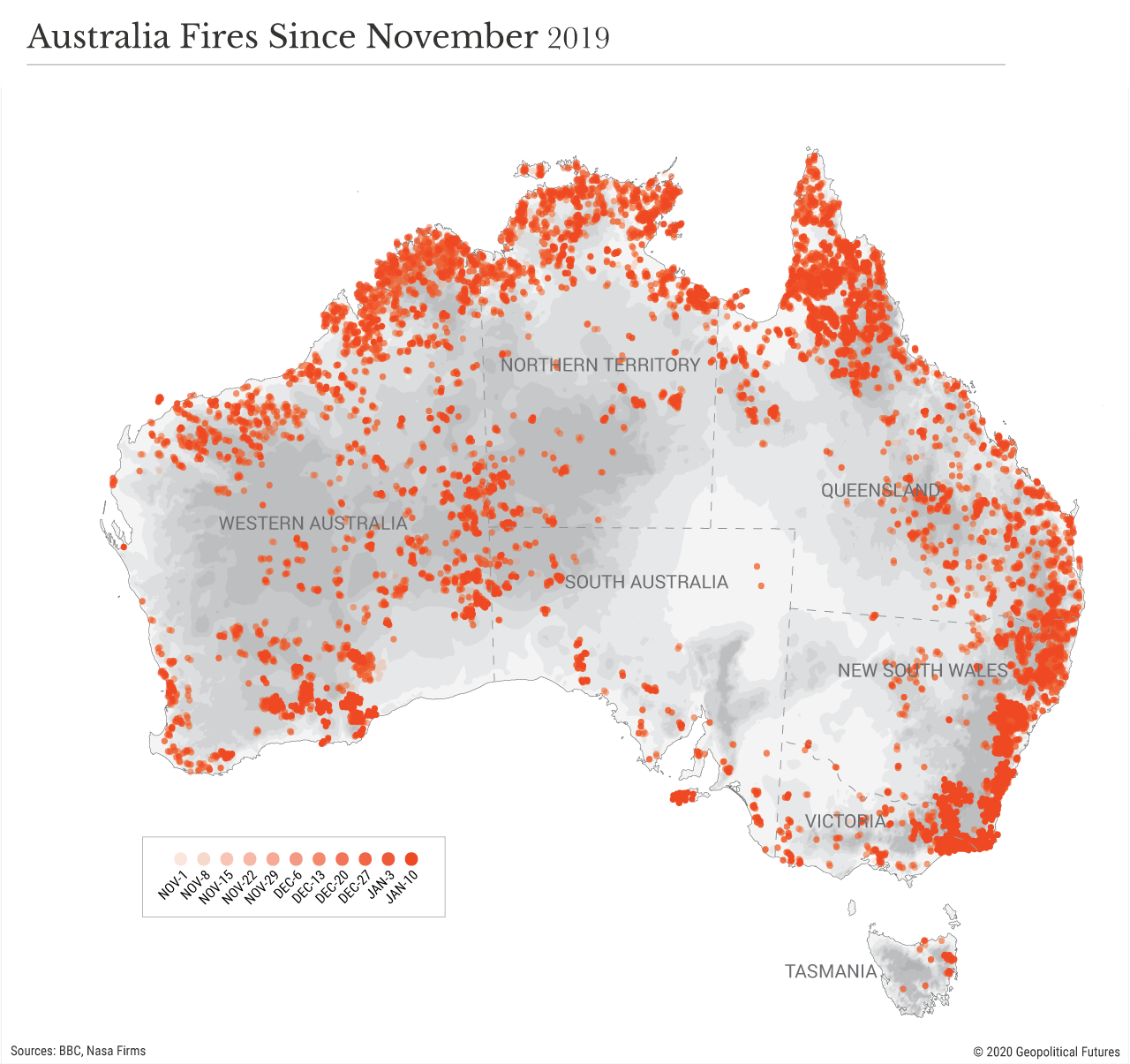

Bushfires have been raging across Australia for the better part of four months. High temperatures and smoke-filled skies have enveloped a swath of land bigger than some countries, threatening countless species of plants and animals. (I admit I checked in daily on the recovery prospects for Lewis the Koala. RIP little guy.)

The tragedy has been well documented, but its potential ramifications have not. With that in mind, we’ll take a look at how the fires could affect Australia’s military, economy and political landscape and its behavior on the global stage.

Natural disasters are a fact of life, of course, and tend to be unique to certain regions. The Caribbean has hurricane season. India has monsoons. Australia has bushfire season. Conditions this year were unfortunately well suited for the outbreak. Australia’s eastern states have been in a drought since early 2017. The first few months of 2019 were the driest on record. And much of the native flora, including eucalyptus trees, are naturally highly flammable to begin with. In other words, the area was a tinder box surrounded by an endless supply of fuel. High winds, some clocking in at 70 kilometers (44 miles) per hour, spread the fires more rapidly. As a result, the current bushfire season started earlier than normal, while temperature and precipitation relief won’t come until mid-March.

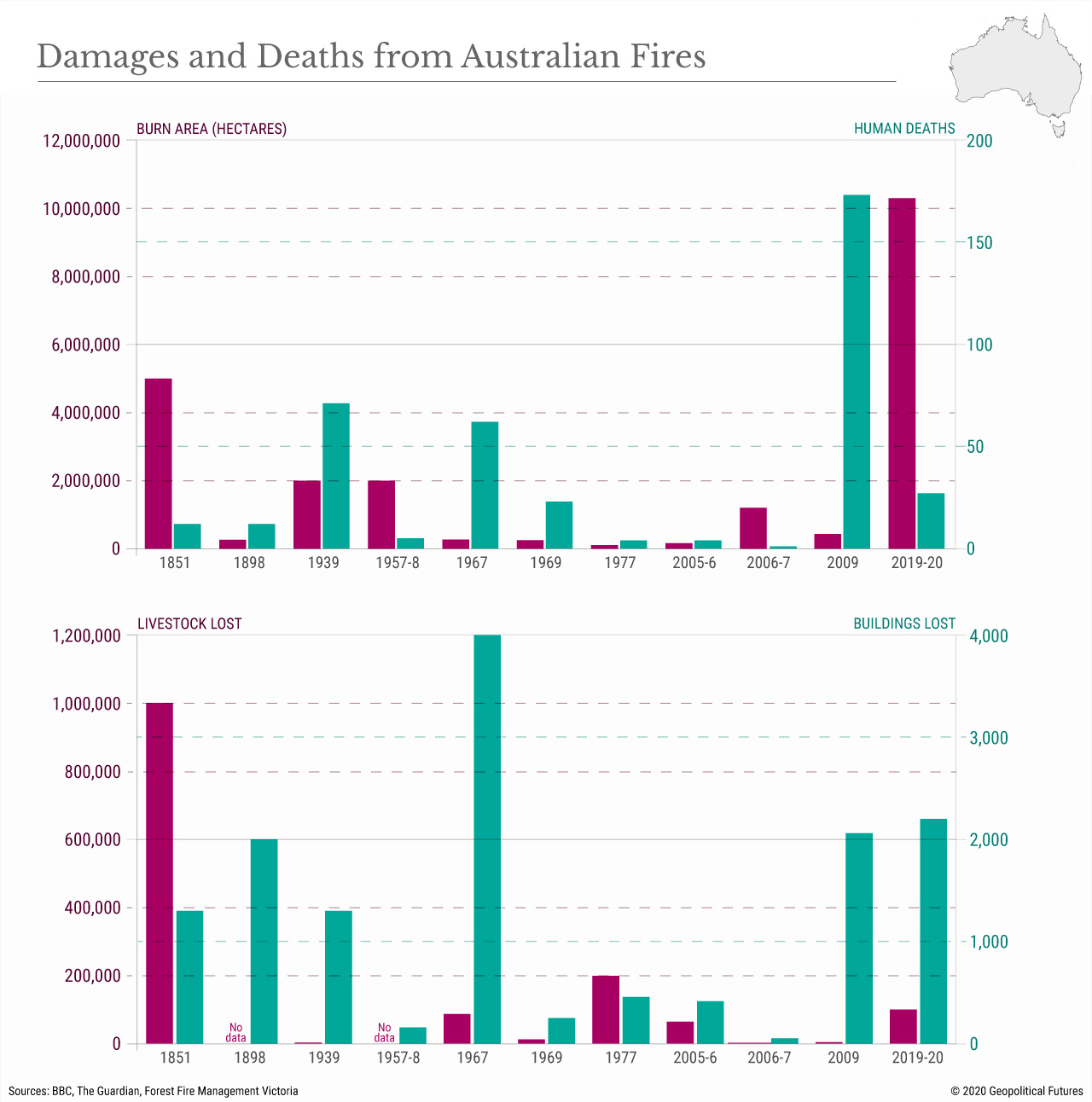

It’s difficult (and perhaps somewhat gauche) to quantify how much worse the current fires are to past ones, but comparing the affected areas, deaths and property damage is instructive. This season, some 10 million hectares have been affected, surpassing the affected area of any previous season on record. So far, the fires are less deadly than in previous years, with just under 30 people killed. (This excludes the loss of wildlife, which some say is in the billions. Historical data for animal death is hard to come by.) In terms of property damage – which can be measured through insurance claims, buildings burned and loss of livestock – the current fires are disastrous. Estimated damages are 2 billion Australian dollars ($1.4 billion) and growing; the previous record was about AU$ 4.4 billion in 2009.

Strategy and Security

Australia’s most strategically sensitive military installations include naval bases along the northern coast, which are far removed from the bushfires. Installations nearer to the fires are reportedly intact. The fires have not interrupted military operations overseas or domestically. In fact, the armed forces have played a critical role in evacuation missions and supporting firefighting efforts.

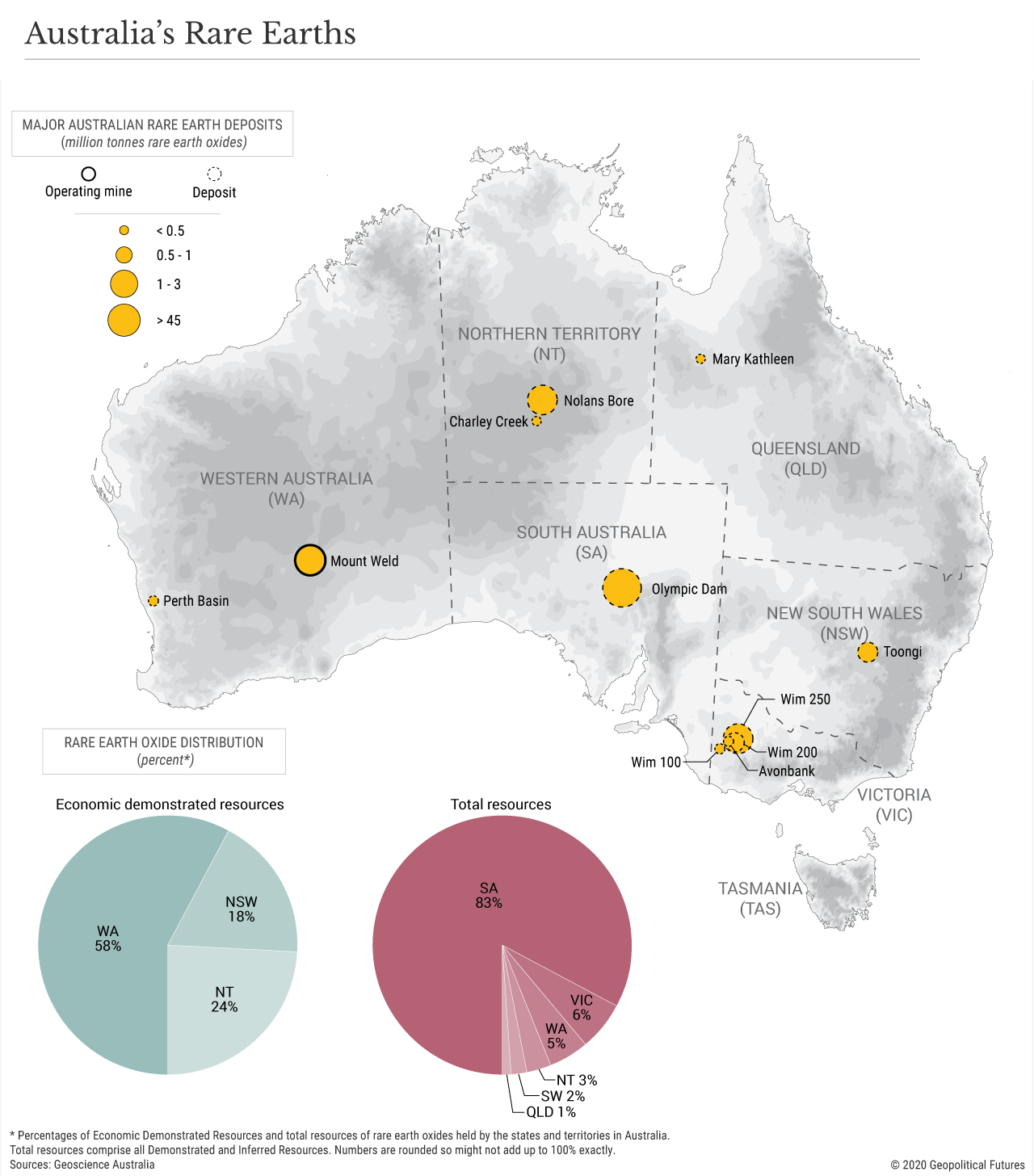

Of course, national security involves more than just military equipment – it also entails strategic resources necessary to sustain it. Australia boasts an abundance of rare earth mineral deposits and production. These minerals are relatively scarce and play a critical role in the supply chain for technology, aerospace and telecommunications. China holds a near-monopoly on the world’s supply of rare earths, which is a problem for the U.S. and allies such as Australia. The deposits are therefore a necessary step in their shared efforts to mitigate supply chain risk by building an alternative sourcing network for rare earth minerals. But here, too, the fires appear to be negligible, since producing mines are located away from the deposits and associated infrastructure. Notably, Australia is also a global leader in the export of coal and liquefied natural gas, which are also relatively unaffected by the fires. The real challenges facing the mining industry are maintaining water supplies critical to operations despite the drought and weathering the political storm being stirred up.

Economic Damage

The damages and material losses due to the bushfires do not impact Australia’s economy evenly. Some areas are directly affected, some damages come from secondary or delayed effects, and still some parts may actually benefit once the fires are put out.

The first casualties, potential or real, are the insurance, agriculture and tourism sectors, of which agriculture is the most geopolitically relevant. (Insurance is domestic and 75 percent of tourists are domestic.) Australia is a major global supplier of beef and dairy. Its dairy industry, valued at AU$3.3 billion, ranks fourth in the world for exports and is a leading supplier to Asian markets. The fires threaten 12 percent of the national sheep flock and 9 percent of the national herd. The Federal Agriculture Ministry anticipates livestock losses of more than 100,000 head. Supply disruptions have already been reported. Another key agriculture sector, wheat, has not been directly affected because the harvest was completed before the fires came into full effect. Even so, the fires threaten grain stocks, livestock feed and future crop yields. Exposure to intense fire usually decreases the nutrient pool in soil and the capacity to retain water, making it more difficult to grow crops in the future.

The wildfires have aggravated an already troubled agriculture industry. Dairy and wheat production were already in decline, thanks to the ongoing drought. Australia’s milk production reached a 22-year low. Wheat production was so low that it had to start importing in mid-2019. Early estimates suggest production could decline by another 8 percent in 2019-2020. Consumers will start to see the impact of the fires in the supply and pricing of related basic goods. Domestically, this will manifest itself on the political front (more on that below). Importers will also experience price hikes. Buyers have already sought out alternative suppliers as they offset Australia’s production decline. Some countries will be more able to absorb the price increases than others. Consider China, which is very sensitive to even small food price fluctuations. The trade war and the swine flu have inflated food prices already, and though Beijing has found alternative suppliers in Brazil and Argentina, other drivers pushing up food prices will make food less affordable for consumers and increase pressure on the government to keep them low.

SGS Economics and Planning estimates that fire-related losses this fiscal year will run AU$1.1 billion-AU$1.9 billion. This includes indirectly affected areas such as Sydney, which is losing as much as AU$50 million per day because of changes in worker and consumer habits. Economists at AMP Capital suggest Australia could lose the equivalent of 1 percent of its national economic output. Yet, the government has already authorized AU$2 billion over the next two years for reconstruction – a modest disbursement for a country with a gross domestic product of about $1.38 trillion. On a purely macroeconomic level, Australia should be able to weather the firestorm.

Political Implications

Any emergency or natural disaster puts political management under the microscope – and Australia is certainly no exception. But the timing is particularly bad for the government in Canberra, which has experienced a lot of turnover in the past decade. The fires have renewed public debate over the mining industry and have raised questions over the government’s ability to respond to Australia’s needs.

Though mining is one of Australia’s globally significant activities, the future of this industry is a rather divisive issue. Mining accounts for about 10 percent of Australia’s GDP and employs tens of thousands of people. The country also ranks as one of the world’s leading coal and LNG exporters. The prime minister and his party have strongly supported the country’s extractive industry, but the fires have emboldened the industry’s critics, giving them some momentum in debates over reducing Australia’s carbon footprint. To be clear, Australia isn’t about to suspend its extractive activities. But political battles matter, and for now, the ruling party is on the defensive.

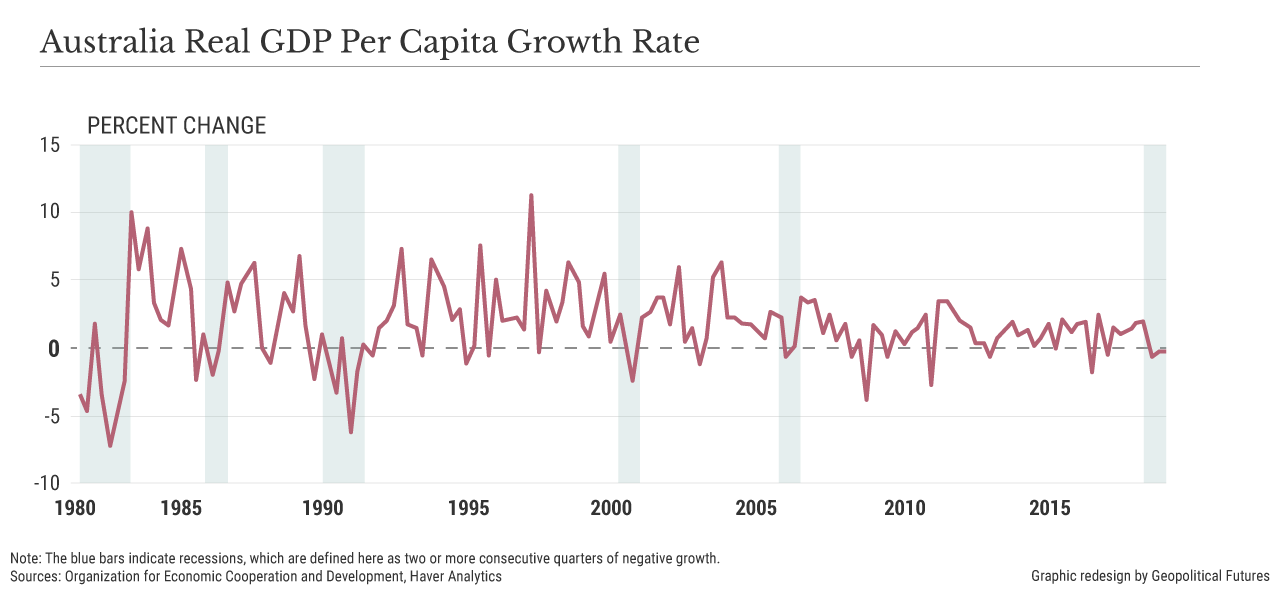

At the same time, the cost of the fires has called into question the government’s general economic management. While the country’s national GDP has grown for nearly three decades, consumers have on several occasions experienced recession-like scenarios, leading to declines in per capita GDP. Wage growth has all but stalled. Consumers are understandably angry about rising prices of basic goods. And there’s only so much the government can do to jumpstart the economy through interest rates. The Central Bank had reportedly planned to cut interest rates early this year; the fires will only mitigate whatever effects may have come from the policy.

Which is all to say that the fires didn’t start Australia’s political problems but certainly aren’t helping them. The country has become fairly adept at churning out new leaders, so even if the pressure builds to a point that the public wants a new prime minister or party, the global impact will be minimal. Australia’s two most important relationships – its alliance with the United States and its wary approach to China – will be largely unfazed. Australia’s current security and economic needs keep this dynamic in place even under the most dire natural disasters.