By Antonia Colibasanu

The Russian government announced yesterday that, considering the difficult fiscal environment, it plans to increase the use of interregional budget transfers to help poorer regions. Russian regions have seen their debt increasing during the last few years and have reached out to commercial banks for loans and bond issues to get cash and service some of their debt, even though Moscow has offered them cheap loans.

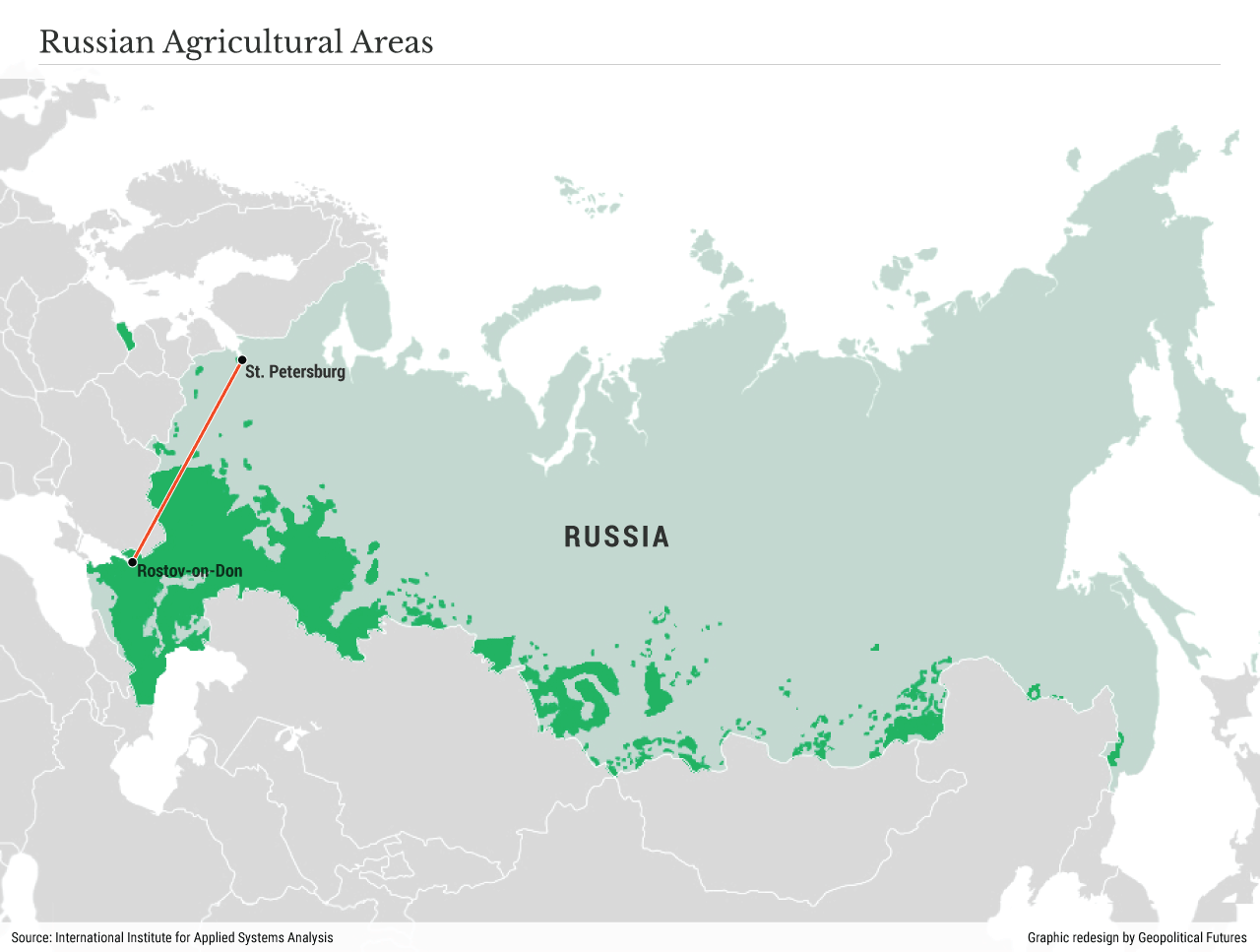

Russia’s vast geography has always been a challenge for its leaders. The country’s immense landmass is disproportionally populated because of its climate. Much of the Russian population lives north of the 50th parallel, which is even further north than Canada’s main population centers. This makes agricultural production scarce. Population density and urbanization rates are higher in the western regions, which have seen greater commercial development, considering their access to river routes. These factors have resulted in dramatic differences between rural and urban Russia and between western and eastern regions. These differences are highly problematic during times of economic crisis.

It is not a surprise that Russian regions have debt – but since Russia has entered its second economic recession in less than 10 years, social problems have increased. While the regions are expected to administer their budgets independently, the federal government usually comes to their rescue, bailing them out. But the government has seen revenues decline since the drop in oil prices, considering that more than 50 percent of budget revenues come from oil exports. Russia may exhaust one of its reserve funds next year, due to declining oil revenue.

Earlier this month, the Russian Ministry of Economic Development released its economic forecast for the next three years, showing anemic growth rates – under 3 percent – for both scenarios it considered. The other key factor that will determine growth is the inflation rate, which will affect ordinary Russians. Numbers are great for writing reports, but to the average Russian citizen, purchasing power is what really matters.

Russia’s Federal State Statistics Service announced that disposable income fell in August by 9.3 percent in annual terms, the steepest decline since August 2009, just after the global financial crisis. This news accompanies reports on the rising number of Russians who are growing their own food to supplement their food supply. Some Russians have started volunteer food-sharing programs to collect food from restaurants and distribute it to those in need as the number of struggling families grows. While such reports may sound alarmist, famine and limited food supply have been issues for Russia historically. Due to the country’s climate, only 13 percent of the land is suitable for agricultural use. The transportation network in the country doesn’t allow farmers to efficiently send their products to urban areas.

Moreover, the country’s development model for more than half of century has been based on industrialization that depended on natural resource exploitation. However, in Russia, areas rich in natural resources also have higher population density than the rest of the country and are highly vulnerable to fluctuations in the economy and commodity prices. In April, the World Bank said that an estimated 3.1 million Russians have slipped below the poverty line and the increase in poverty will continue.

The struggling economy therefore threatens to weaken social stability in the country. The latest poll released by Russian research group the Levada Center indicates that 34 percent of the population believes the government is not providing citizens with adequate social security. Taking into account the potential for increased instability in the country due to the dire economic conditions, the Kremlin started looking at potential economic reform programs early this year. But, as parliamentary elections took place on Sept. 19, no announcements have been made yet. However, there were hints that a new taxation system will be implemented and that pensions may be indexed to the level of inflation again.

After President Vladimir Putin’s party, United Russia, won a landslide victory in the election, the president addressed the country’s economic woes in his victory speech, pointing to reforms that need to be carried out. Amendments to the budget proposals for 2016-2019 will be discussed at a government meeting on Oct. 13. Privatization of oil producers Rosneft and Bashneft has been discussed as a way to raise much-needed cash for the government’s budget, though both companies face the challenge of finding a willing buyer at the desired price. Discussions on defense expenditure cuts have gone on for months now. It is therefore likely that unpopular decisions will be made in the coming months as the Kremlin needs to address the economic situation sooner than later, with presidential elections coming up in 2018.

At the same time, Moscow will maneuver carefully to ensure it does not increase instability. Protests have been taking place in the regions since earlier this year. These have included riots in the city of Smolensk in April, as residents were unhappy with the rise in utilities costs, and a convoy of tractors and cars from Kuban that drove into Moscow in August. Observing the rising danger of regional unrest, Putin has been building up the security apparatus to increase control throughout the country.

Since January, we have seen reshuffles at top levels of law enforcement and security sectors, which have resulted in a renewed, younger guard of Putin’s loyalists placed in key positions. At the same time, Putin announced in April the formation of the new National Guard, through which he has direct control over two essential processes: getting intelligence on potential unrest in the regions and ending any protests.

In addition, Russia’s Kommersant newspaper reported on Sept. 20 that Russia will resurrect the Ministry of State Security, combining the Federal Security Service with the Foreign Intelligence Service and the majority of the Federal Protection Service units, which oversee the protection of the country’s top leaders. The ministry will start operating before the presidential elections in 2018 and will reportedly be engaged in the highest profile cases, one of its functions being to root out corruption in law enforcement agencies. Corruption is both an electoral campaign issue for Putin and a phenomenon that has undoubtedly negatively affected the structural development of the country. The fight against corruption led by the Kremlin will have political functions as well, considering the Kremlin’s need to keep tight control over the country.

Russia is facing troubling times – all pointing to our forecast that Russia will face a major crisis by 2020. With a declining economy and limited options to address rising social problems, vulnerabilities for Putin will increase. The fundamentals of Russian geopolitics indicate that he must keep Russia united. He sees controlling security structures as key for keeping the country unified and under his rule. At the same time, as his power and the economy weaken, unpredictability will rise for Russia, especially in key strategic borderland regions like Ukraine, the Caucasus and the Black Sea.