U.S. and Chinese trade negotiators appear to have made a breakthrough on a “phase one” trade deal. Of course, it’s just a handshake deal, bereft of details that, according to U.S. President Donald Trump, would be papered eventually. And, of course, as we saw when negotiations collapsed abruptly in May, declaring success before the stickiest points of contention have been fully ironed out can backfire. Chinese President Xi Jinping won’t risk weakening his position at home by meeting with Trump at the upcoming Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in November if there’s any chance of walking away empty-handed.

Nonetheless, what’s important now is that the U.S. appears willing to settle on a deal that overwhelmingly ignores the stickiest points of contention altogether – at least for the time being. And recent moves from China suggest that it thinks a window of opportunity has indeed opened to lock in the handful of points where agreement is possible. A long-delayed Chinese Communist Party conclave this week will shed light on just how far Beijing is ready to push forward with critical reforms the U.S. is demanding.

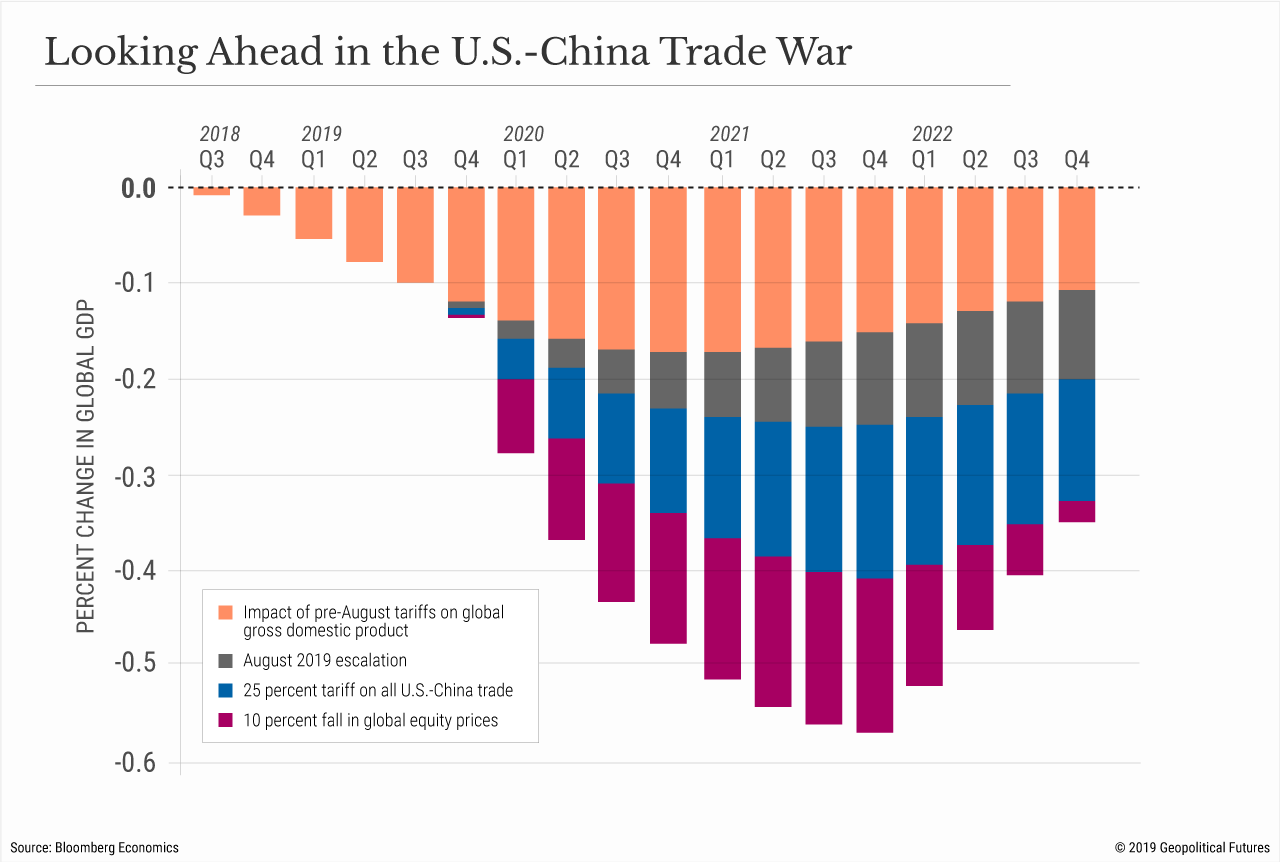

At this point, even a limited, largely symbolic agreement would be a big deal to the extent that it staves off future escalation by the United States and shields U.S. businesses and consumers from the round of tariffs – by far the most painful – scheduled for mid-December. Just don’t expect this particular deal to do away with the bulk of existing tariffs, much less to resolve the underlying drivers of the dispute. Steep political constraints on Beijing will make a more comprehensive settlement even harder to reach down the road. Ultimately, the prospects of a final deal will hinge on just how much the United States, not China, is willing to cave.

Why China Looks Serious About a Deal

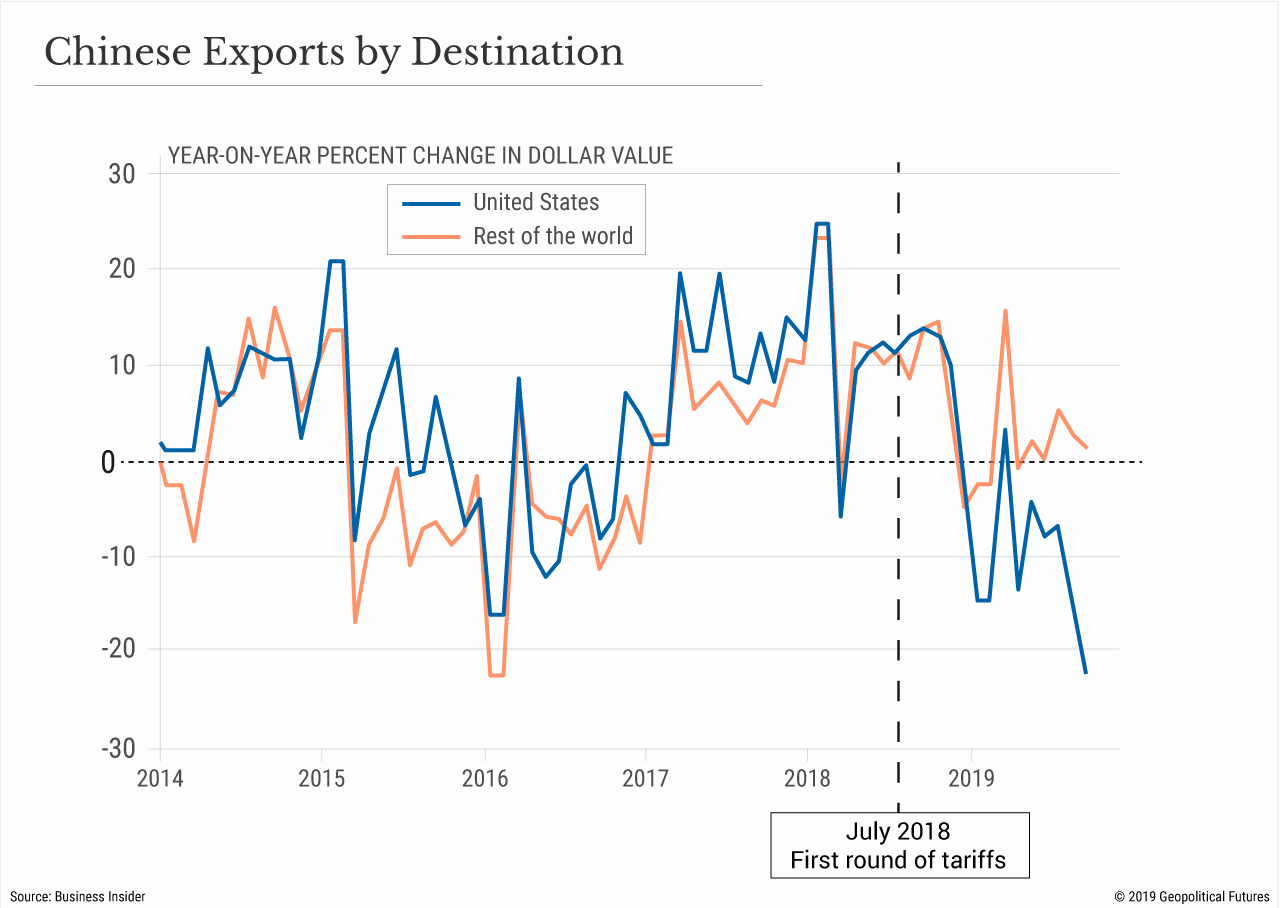

The trade war is far from China’s biggest economic problem, but it’s nonetheless starting to become a problem. U.S. imports from China have fallen 12.5 percent so far this year, compared to 2018. An International Monetary Fund forecast released this week said Chinese growth will plummet by another 1.6 percent next year if Trump follows through on his threats to tax another $267 billion worth of Chinese imports.

It’s unsurprising, then, that over the past two months, Beijing has been quietly laying the groundwork for concessions needed to strike at least a “truce” with the U.S., if not a more substantive deal. On Friday, for example, it confirmed that a deal would include a pledge to keep the Chinese yuan stable in relation to a basket of currencies. Also in the past few weeks, Beijing lifted caps on foreign ownership in the asset management and auto industries, passed a new foreign investment law that received widespread positive reviews, and pledged a host of new measures such as export tax rebates, improved trade financing and credit insurance. It expanded quotas for tariff-free imports of some U.S. farm goods. According to U.S. officials, Beijing has also committed to make new concessions on intellectual property protections.

Senior Chinese officials, meanwhile, have been on a PR blitz at home and abroad aimed at wooing foreign investors. Most prominent among them has been Premier Li Keqiang, a longtime economic liberalization advocate, and Vice President Wang Qishan, Xi’s trusted “firefighter” who is held in relatively more high esteem abroad. When Li and Wang take high-profile trips abroad and feature prominently in Chinese state media, it’s often a signal of growing concern in Beijing about its souring reputation in foreign business circles (and, occasionally, hints at a power struggle in the upper echelons of the CPC).

The timing of the CPC’s Fourth Plenum this week is also noteworthy. Beijing was expected to hold the plenary session a year ago, per tradition, but delayed it about as long as possible under party rules. This, combined with occasional hints of dissent about Xi’s reassertion of state control over the economy, suggested deep factional divides may have been emerging within the party over China’s handling of the economy, including the trade war. Xi is loath to risk having these divides on display at the plenum, so the fact Beijing is finally moving forward with the meeting, along with the aforementioned rollout of various reforms, could suggest he’s succeeded in restoring enough consensus for China to move more aggressively with reforms going forward.

More likely, though, the plenum will underscore the reality that Beijing is still operating amid tight political constraints and trying to thread the needle between a number of bad options. Based on official releases, at least, the emphasis of the conclave will be on themes like ideological purity, party loyalty and combating the evils of Western-style capitalism – not, say, the virtues of reform and opening. This would suggest that Xi remains preoccupied with restoring party solidarity and appealing to nationalist forces to curry support. When the party leadership gets nervous, it typically either gets trapped in paralysis or resorts to the tools it trusts most to entrench its power. In short, China wouldn’t be capable of inking anything more than a “truce” anytime soon. The plenum will be held behind closed doors, so watch for subtle shifts in state media coverage, unexpected personnel changes and so forth for clues on Beijing’s ability to move decisively in one direction or another.

What a Deal Won’t Resolve

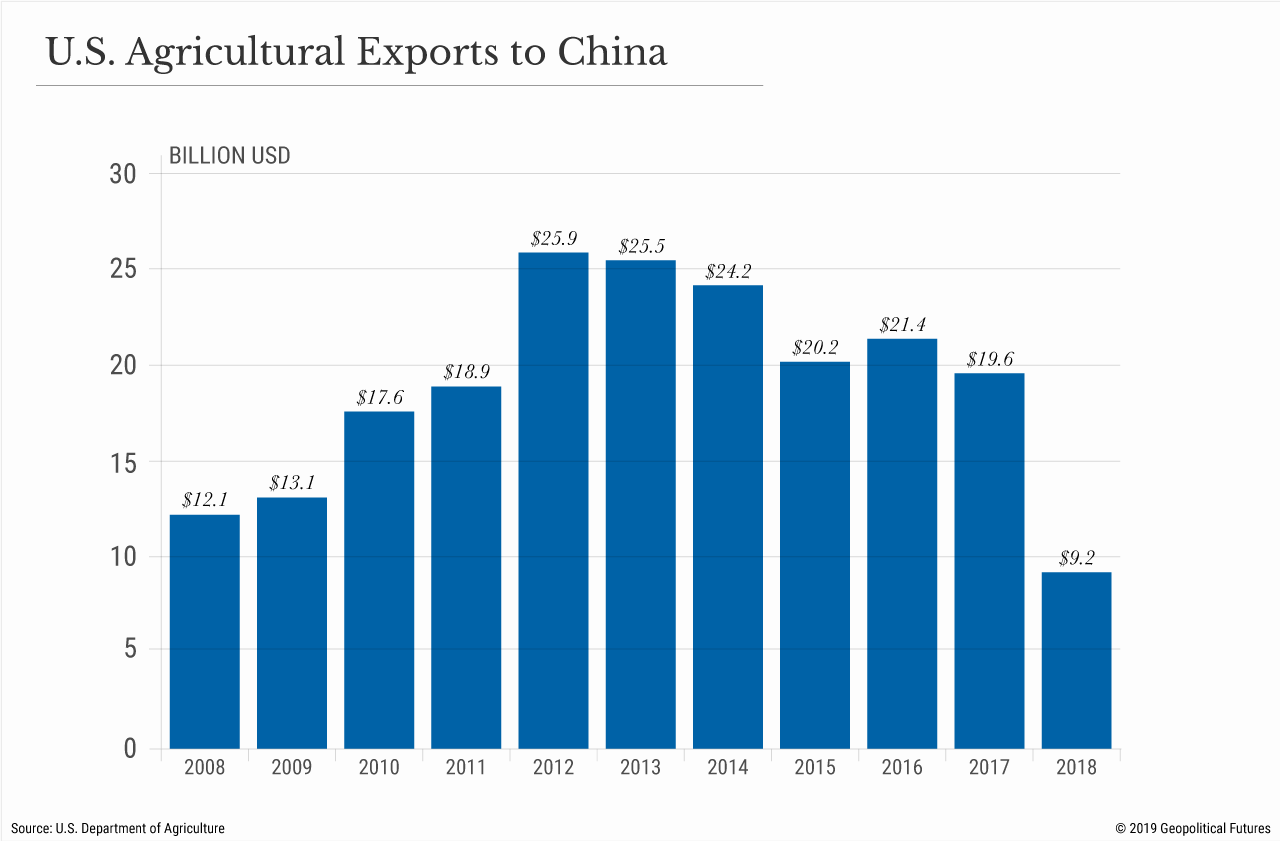

Already, it’s fairly clear what won’t be resolved in the immediate future, even if a phase one deal is finally put on paper. There’s a common theme among China’s recent moves and expected concessions: They’re all measures China increasingly needs to do anyway. Its moves to boost foreign participation in its financial sector, for example, come on the heels of a near-crisis in which the Chinese banking sector, especially state-owned lenders, proved exceedingly ill-suited for channeling funding to the private sector. The resulting credit crunch did far more damage to the Chinese economy than U.S. tariffs have yet to do. China’s increased agricultural purchases would come at a time of surging food prices resulting from a devastating outbreak of African swine fever. If it agrees, as reported, to a deal on stabilizing the yuan, it will be at least in part because it hasn’t been intentionally driving down its currency and has a crippling fear of capital flight.

Similarly, its measures aimed at wooing foreign investment come amid mounting concerns about the country’s reputation as a place increasingly hostile to foreign businesses. Beijing needs new foreign investment to sustain employment, boost its flagging growth, and stem the slow-motion exodus of foreign firms to other low-cost manufacturing hubs. Moreover, it has long relied on Western business circles to block anti-China and protectionist political forces abroad from translating into punitive policy measures. But over time, as homegrown competitors to foreign firms began hoarding market share in China (with ample help from the state), and as well-documented allegations of things like intellectual property theft proliferated, disenchantment among foreign firms with the Chinese model has become widespread. This is why opposition to Trump’s trade war has proved manageable for the White House. Beijing won’t be able to make the sweeping changes needed to restore foreign confidence. But it makes sense for it to bend over backward to at least appear to be sincere about addressing foreign firms’ concerns.

In contrast, there’s been nary a hint of evidence that Beijing is preparing to make concessions on the main U.S. grievances. On some issues, like forced technology transfer, there’s realistically not that much Beijing can do to fully snuff out the practice. On others, like more meaningful IP protections, it can pass new laws and push courts to enforce them, but it sees such U.S. demands as an infringement on Chinese sovereignty and is thus loath to spark a nationalist backlash by following through with a gun to its head.

On the biggest issues, moreover, Beijing is going in the opposite direction. Its structural slowdown, trade pressure and soaring debt risks are forcing it to lean even more heavily on the state sector, for example. And to avoid falling into the fabled “middle-income trap,” bolster the People’s Liberation Army and reduce its dependence on foreign technologies, it’s doubling down on its support for advanced manufacturing sectors. Deepening state control at the expense of market-driven dynamism may ultimately do more harm than good to China’s economy and industrial development. But resistance to liberalization from entrenched state-sector stakeholders in China, combined with the party’s existential fear of widespread job loss, means Beijing is defaulting to the tools it trusts most to sustain stability.

There are also a number of points of contention that the U.S. itself isn’t willing to negotiate on – particularly those with national security implications resulting from China’s development of “emerging and foundational technologies.” As we’ve long said, the U.S.-China “tech war” will far outlast the trade war. U.S. concerns over military issues or things like Hong Kong will also remain separate. Thus, expect U.S. measures targeting Chinese tech firms like Huawei, scrutiny on research and development collaboration, and inbound Chinese investment to only intensify from here. And since the U.S. will need to hold on to leverage to ensure implementation of whatever Beijing concedes on trade, expect most of the existing tariffs to remain in place for the time being as well.

The U.S. will still have ample political and economic interest in striking a more comprehensive deal. The tariffs are accelerating the U.S. downturn, and an election year is approaching. And while the U.S. needs to do far more to reset its trade relationship with China and find ways to pressure Beijing to change, the problem for the U.S. is twofold: One, reaping the easy, low-hanging fruit in negotiations now leaves only the hard stuff. Two, absent a cataclysmic loss of CPC control, Beijing can’t and won’t concede on most of the hard stuff just to get out from under tariffs. Rather, they’ll just push China deeper into its shell.