Originally produced on Sept. 11, 2017 for Mauldin Economics, LLC

By George Friedman, Xander Snyder and Ekaterina Zolotova

Low global energy prices have been a strain on the finances of many oil producers, but they’ve hit Russia particularly hard. Oil and gas accounted for 43% of Russia’s government revenue in 2015 and this figure was expected to drop to 36% in 2016, according to the World Bank. But this declining percentage doesn’t mean the government has become less dependent on energy; it’s simply a reflection of low energy prices.

And with its financial resources dwindling, Russia’s ability to defend against both external and internal threats will be severely tested. After all, the country will be hard pressed to find the cash needed to fund its defense and social welfare programs with declining revenue from one of its most important industries. As a result, the government will have to find new ways to raise revenue.

One option is reforming the personal income tax system. President Vladimir Putin has given some indications that he’s considering changing the current flat income tax rate to a progressive system. Another proposal, which is now being reviewed by Alexei Kudrin, an economic adviser to the president, is to raise the personal income tax rate from 13% to 17%.

At the current rate, personal income taxes make up 10% of all government revenue and 18% of all tax revenue. Raising personal income taxes would help the government reduce its dependence on energy. But the government can only make this move if Russians can afford to pay a higher rate.

A Model of the Average Russian

We therefore decided to stress test Russia’s income tax rate in order to determine how much savings an individual is left with after paying all their expenses. This will help determine whether a 4% hike in the personal income tax rate is feasible.

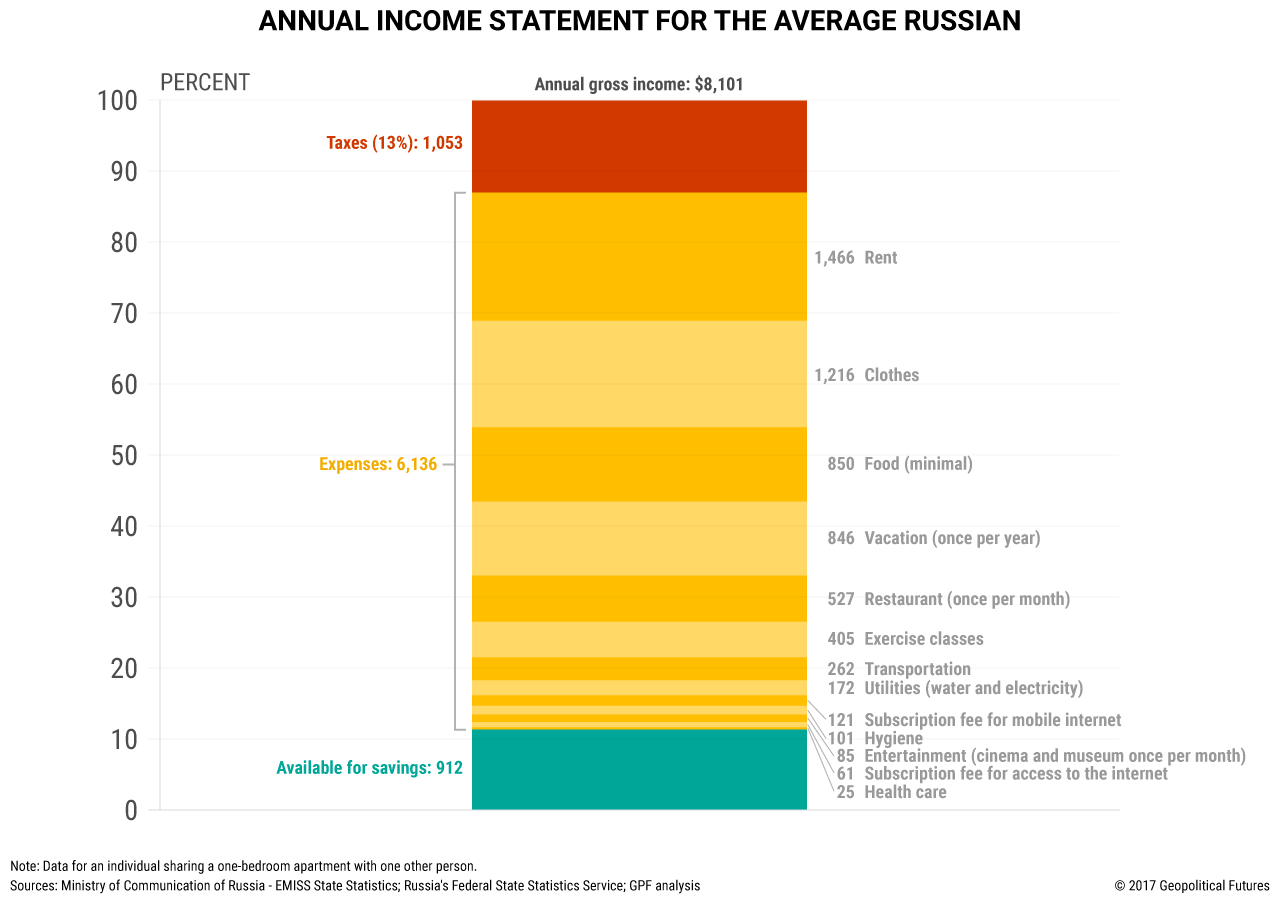

We did this first by constructing a sample budget for an average Russian citizen based on statistics provided by GKS, Russia’s statistics agency.

According to GKS, the average annual gross income per person is $8,100. We calculated expenses by adding costs for rent, clothing, food, and certain leisure activities like eating out, going to the movies, and vacation. Food costs are based on the minimal food consumption figures provided by GKS. We also included some healthcare costs for visits to a private dentist and doctor once per year, but since Russia has a public healthcare system and employers typically provide health insurance, we didn’t include the cost of health insurance in our analysis.

In our model, rent covers a one-bedroom apartment shared by two people, both of whom contribute to the rent. Based just on this indicator, some regions would have few people with sufficient income left over to cover their monthly expenses. This factor alone reveals some of the inflexibility facing the Russian government.

If people are willing to share their apartments with more people—employed adults rather than children or other dependents—then their share of the rent will decrease. But this would mean sacrificing living quality in exchange for greater savings—a tradeoff not everyone is willing to make.

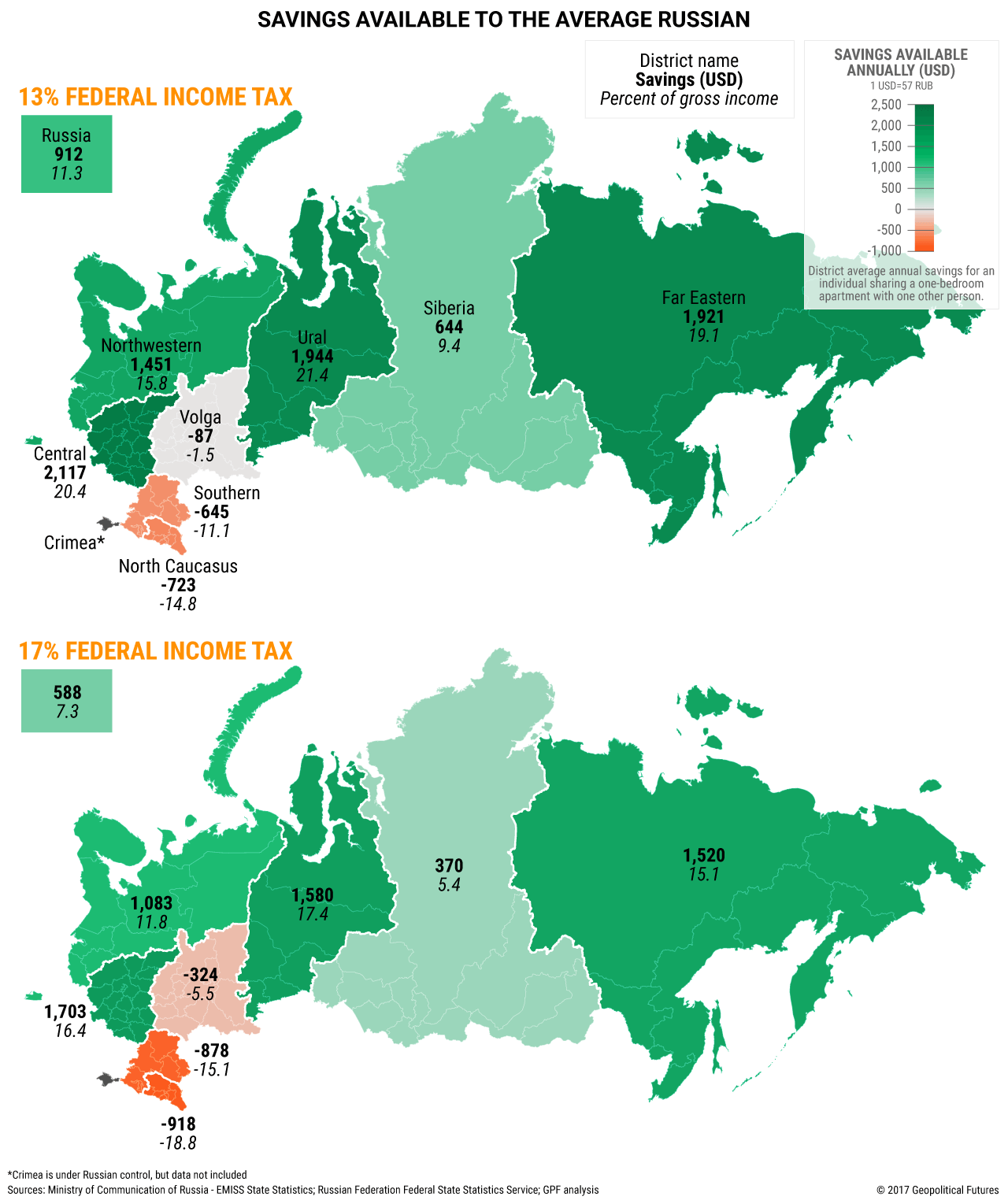

Based on this model, the average Russian will have roughly 11% of their gross income left over for savings after paying the current 13% tax rate. This may seem to give the government some leeway to increase income taxes, but Russia is a large country with varying degrees of economic productivity and standards of living. We therefore adjusted income and expenses for each of Russia’s eight federal districts to see the variation in savings for the different districts.

We then applied the proposed 17% rate to see how much savings the average Russian would have at the higher rate. At 17%, the average Russian will see savings decline to 7.3% of their income.

Vulnerability in the Caucasus

A few conclusions can be drawn from the maps above. A 4% increase in personal income taxes wouldn’t necessarily break the bank for the average citizen. But under our model that assumes two people are sharing rent for one apartment, residents in three out of eight federal districts are already unable to pay for their expenses, and all three of these districts are in Russia’s southwest.

At a 17% tax rate, at least three people would need to split an apartment in the Volga Federal District to break even. In the Southern Federal District, eight people would need to share an apartment to make it affordable. And in the North Caucasus Federal District, eight people sharing an apartment would still leave everyone in that apartment in the red.

This highlights the vulnerability of the Caucasus region in Russia—an area that has historically been a flashpoint not just for Russia but for Europe as a whole. Volga has the second-highest gross domestic product of all the Russian regions. Tatarstan, which is located in Volga, is an area of great economic productivity and is a net contributor to the Russian budget. Yet residents in Volga are struggling to meet their expenses, and those outside Tatarstan are likely even worse off than what our map indicates for the average Volga resident.

The districts with the highest savings rates under the current tax scheme are the Ural, Central, and Far Eastern districts, which have 21.4%, 20.5%, and 19.1% of their total gross income left over for savings respectively. The Ural district contains more than 60% of Russia’s oil reserves and 75% of its natural gas reserves. The Central district includes Moscow, an economic hub for the country. The Far Eastern district, Russia’s largest by size, is its smallest by population. While economic development remains limited in the district, it is rich in minerals and other natural resources.

Weighing the Risks

Russia appears to have some flexibility to increase personal income taxes, at least in some regions. It’s unclear if different tax rates would be applied to different locations under the proposed changes but even wealthy regions are likely to oppose the reforms. Tatarstan’s President, Rustam Minnikhanov, has tried to form a coalition between the former autonomous republics against tax hikes imposed by Moscow, but to no avail.

Ultimately, a tax hike is just one way the government can reduce its dependence on energy and raise funds while oil prices are low. Although oil and gas still make up a significant portion of the government’s revenue, that portion is declining. This move wouldn’t come without some risk, however. Hiking taxes could dampen domestic demand and even result in unrest in wealthier regions. But the alternative—continuing to depend on a resource whose declining value has no end in sight—may be an even bigger risk.