Originally produced on March 12, 2018 for Mauldin Economics, LLC

By George Friedman and Xander Snyder

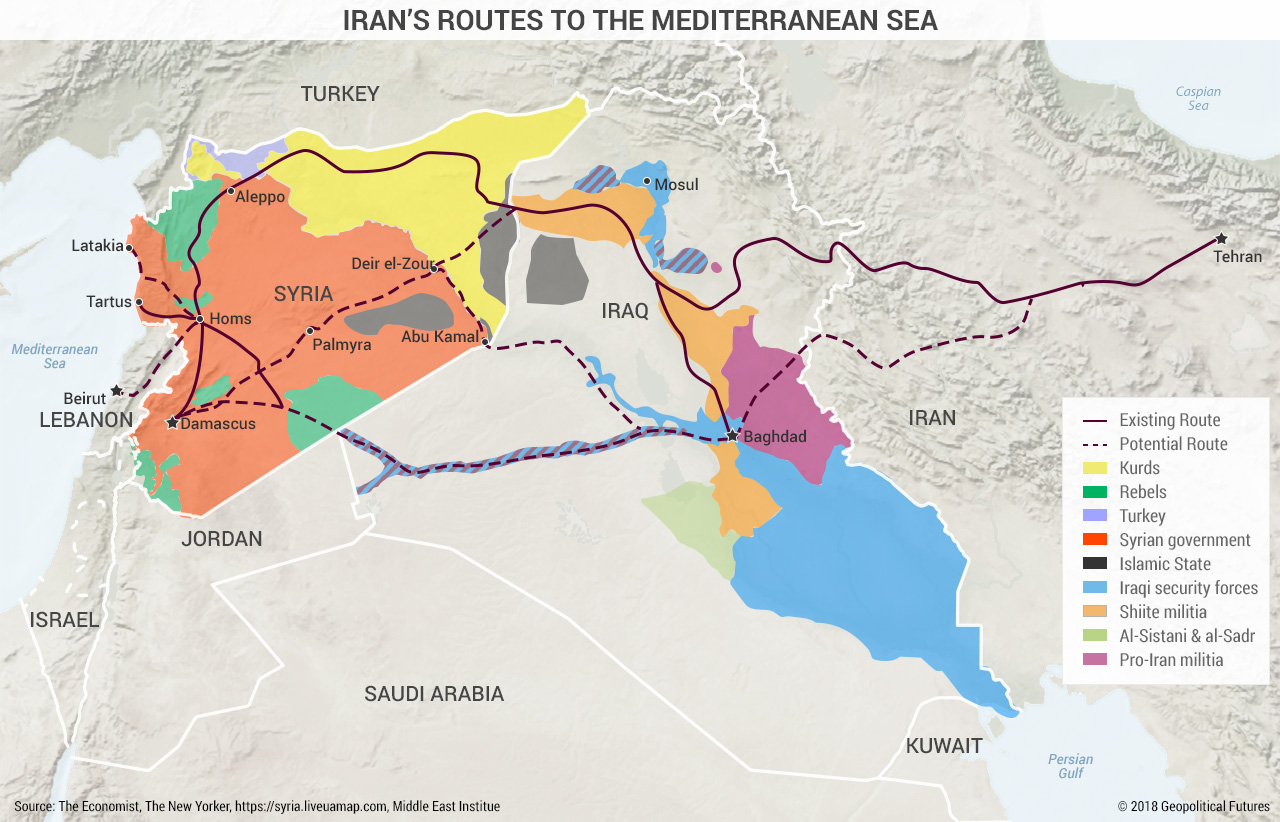

Iran’s activities in Syria get a lot of press, but less attention is paid to what Iran has done in Iraq to make those activities manageable. Iran operates a Shiite foreign legion that over the years has trained 200,000 fighters in Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen. And one part of that foreign legion is the Popular Mobilization Forces in Iraq. The militias of the PMF all but control northern Iraq, which Iran has transformed into a land bridge to supply its other proxy groups in Syria and Lebanon.

The term “Popular Mobilization Forces” was first used in 2013 by former Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki to refer to the Shiite militias in Iraq, but it wasn’t until the fall of Mosul in 2014 that the PMF really came into existence. As IS flooded into the city, Iraqi Shiite cleric Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Husseini al-Sistani issued a fatwa calling on all able-bodied men—regardless of sect—to mobilize and oppose the invasion. Around the same time, al-Maliki signed a decree mandating the formation of the PMF Commission, which administers Iraqi state funds for PMF groups. Iran also discreetly funds some of these groups, and many pro-Iran militia leaders today occupy important positions within the Iraqi government, giving them substantial control over funding decisions… and even battle plans.

According to a report by the Washington Institute for Near East Studies, an American think tank, there are 67 unique PMF militias, approximately 40 of which are pro-Iran in some form or another. Estimates of the total size of all PMF groups vary from 100,000 to 140,000 fighters. Most of these are Shiite fighters, but not all—approximately 25,000 to 30,000 are Sunnis. Minorities like Yazidis, Kurds, and Turkmen also fight in PMF militias.

In 2014, when IS started to advance on Mosul, the Iraqi security forces fled. American support was practically nonexistent, and the Iraqi government was defenseless. The Popular Mobilization Forces came to Mosul’s aid. During the PMF’s siege to retake Mosul, Hadi al-Amiri, Badr’s current leader and an Iraqi member of parliament, ordered a significant adjustment at the last minute.

The original plan was to enclose the city on three sides, leaving open an escape corridor to the west for civilians to flee. Of course, this would also allow IS fighters to escape in the direction of Syria, whose borders are only some 110 miles (180 kilometers) from Mosul along the road through Tal Afar. But Iran did not want IS fighters flooding into the Syrian theater and making the fight harder for Bashar Assad just as he was beginning to turn the tide of the civil war. Under al-Amiri’s revised plan, PMF forces completely enveloped Mosul, forcing IS to fight to the death. The late move also gave pro-Iran PMF groups control of more territory in northern Iraq, which solidified Iran’s supply lines through Iraq into northern Syria. The intervention of an Iraqi politician was therefore instrumental in securing Iran’s control of a northern land bridge through Iraq and into Syria.

PMF Factions

Broadly speaking, there are three main factions within the PMF: those loyal to Iran and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, those loyal to Iraqi Shiite cleric Grand Ayatollah al-Sistani, and those loyal to Muqtada al-Sadr, another Iraqi Shiite cleric known for his populism. Notably, all three of these factions are majority Shiite, meaning the Sunni-Shiite fault line that often defines Middle Eastern conflicts hardly applies in this case. The more relevant division is between Iraqi nationalists and Iran loyalists. Groups that side with al-Sistani and al-Sadr are in the Iraqi nationalist camp.

The pro-Iran groups advocate and fight to further Iran’s interests regardless of whether they conflict with the interests of Iraq. In addition to the funding they get from the PMF Commission, they are usually funded by Iran and report either directly or indirectly to the Quds Force, the foreign expeditionary arm of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard. Further, they support Iran’s vision of a pan-Islamic state that is governed by Iran’s Islamic institutions and, importantly, report to Iran’s supreme leader (a religious-political theory known as wilayat al-faqih, or Rule of the Jurisprudent).

Other Shiite groups, such as those loyal to al-Sadr, advocate a system similar to that in Iran but with a strictly Iraqi nationalist flavor and its own leader. (Al-Sadr would be his own choice as Iraq’s version of supreme leader.) Al-Sistani’s focus, meanwhile, was on defeating the Islamic State, and in the past, he has called for the forces loyal to him to demobilize after beating IS. He has since seemed to backtrack, recognizing that PMF factions are perhaps the best way to resist Iranian influence, not to mention the risk of an IS resurgence.

Iran’s Strategy

Iran’s strategy in Iraq, like its strategy with Hezbollah in Lebanon, is to gradually exercise greater control over Iraqi state institutions. It has already succeeded to a degree, although Iran’s influence is not yet as pervasive in Iraq as it is in Lebanon, in part because of the sheer number of competing factions.

Iran wants a weak, but stable, Iraq. The first part is easy to pursue, but not without endangering the second part. Iran does not want Iraq to be strong enough and nationalistic enough to challenge it outright, which would put its supply routes to Syria and Lebanon at risk and could threaten it with another general war. But if Iran pushes too far, Iraqi state institutions could be imperiled, potentially providing the opportunity for a re-emergence of an IS-like group. Iran also risks triggering a concerted pushback by the Sunnis—either in the form of, again, an IS-like group, or simply staunch electoral opposition. And Iran doesn’t want Iraq to become so divided that secession of any group becomes a possibility. Secession would set a worrying precedent for Iran, which is facing its own domestic political challenges and difficulty in spurring more equitable economic growth.

An ideal situation for Iran is one in which, even if the Iraqi government is not fully under its control, it is weak enough to allow for the ongoing presence of pro-Iran militias. Even if Iran’s militia groups do not become as fully incorporated into the Iraqi government as Hezbollah is in Lebanon, Iran could use its groups to launch attacks in Syria and elsewhere in the Middle East.