China’s real estate sector is one of its economy’s most important assets. Real estate has contributed considerably to China’s transition to a socialist market-based economy and its strong economic growth in recent decades. Now, however, what once propelled the Chinese economy forward threatens to hold it back. Structural economic problems are emerging, and real estate is among the first sectors to show signs of distress. Given its significance to the Chinese growth model, failure to address these issues would likely trigger a crash that would wreck the Chinese economy and disrupt the global economic system.

On paper, there are multiple solutions to the crisis, but they conflict with another of Beijing’s priorities: reducing economic inequality. The inequality-fighting initiative, known as “common prosperity,” has been a major party focus since last year and is codified in the Chinese Communist Party’s current five-year plan. China will need to choose between resolving its real estate crisis or staying the course on common prosperity. While it will try to do both, in the end Beijing will prioritize common prosperity and delay tackling the real estate issue until later.

Seeds of a Crisis

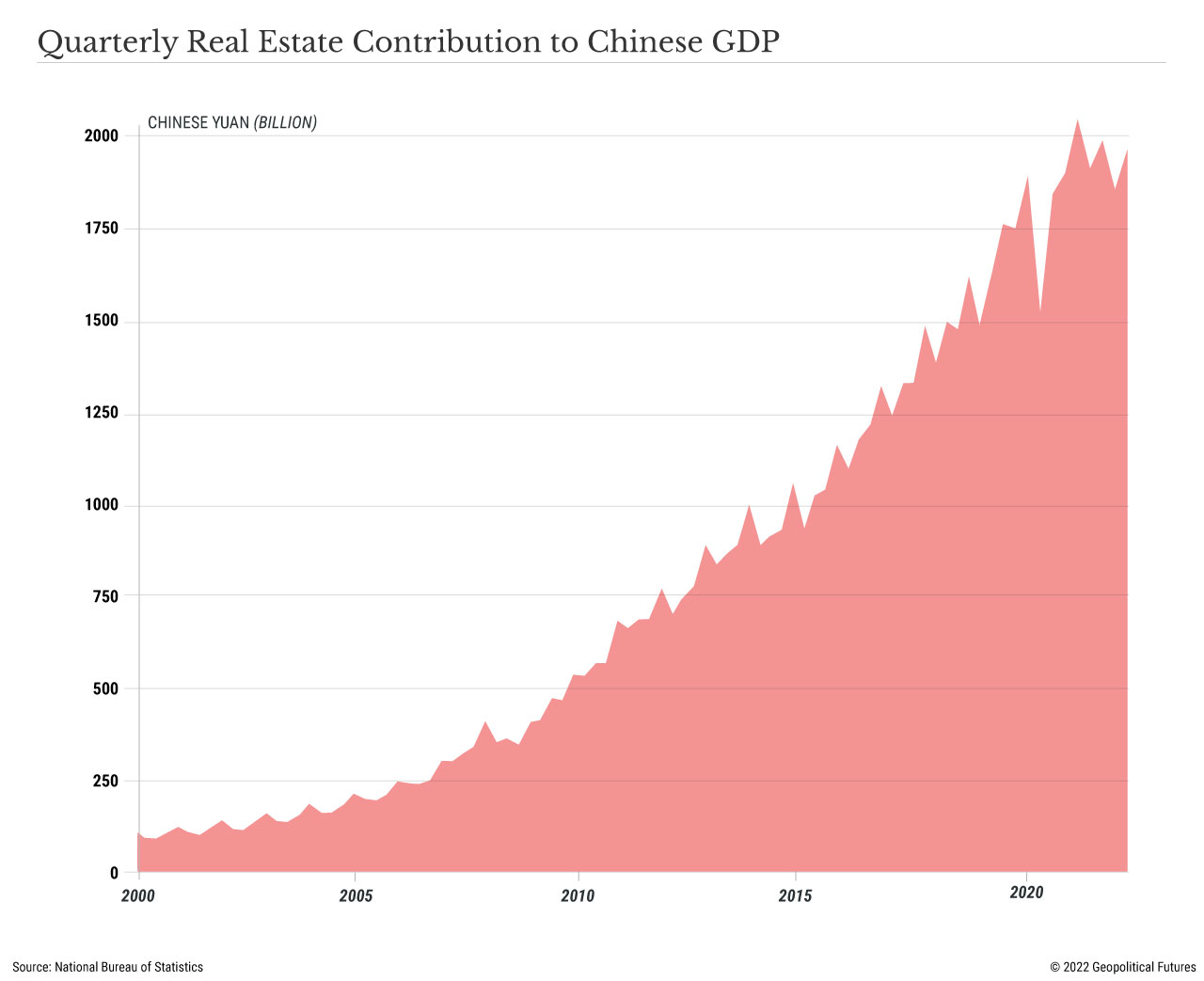

China’s approach to growth – questionable by Western standards – stems from its perpetual need to maintain an economy that can both support a large population and prevent the wealth gap from widening further between the rich coastal cities and the vast interior. The country’s rapid urbanization, evolving financial sector and, just as important, the appetite of domestic and international investors have caused a real estate boom in China that kicked off in the 1990s and has continued ever since.

However, the reliance on real estate for strong and steady growth came at a cost: a reduction in Beijing’s control over market forces. The property market started to expand rapidly from the early 2000s on, as investors and developers assumed that its importance meant the government would backstop it. China depended on the sector’s expansion to maintain high rates of economic growth and households’ net worth, thus any market downturn would be short-lived. This optimistic assumption was true only for a while, though. Beijing soon started trying to contain the speculative fervor and rapidly rising prices – issues that threatened to undermine China’s exceptional economic growth.

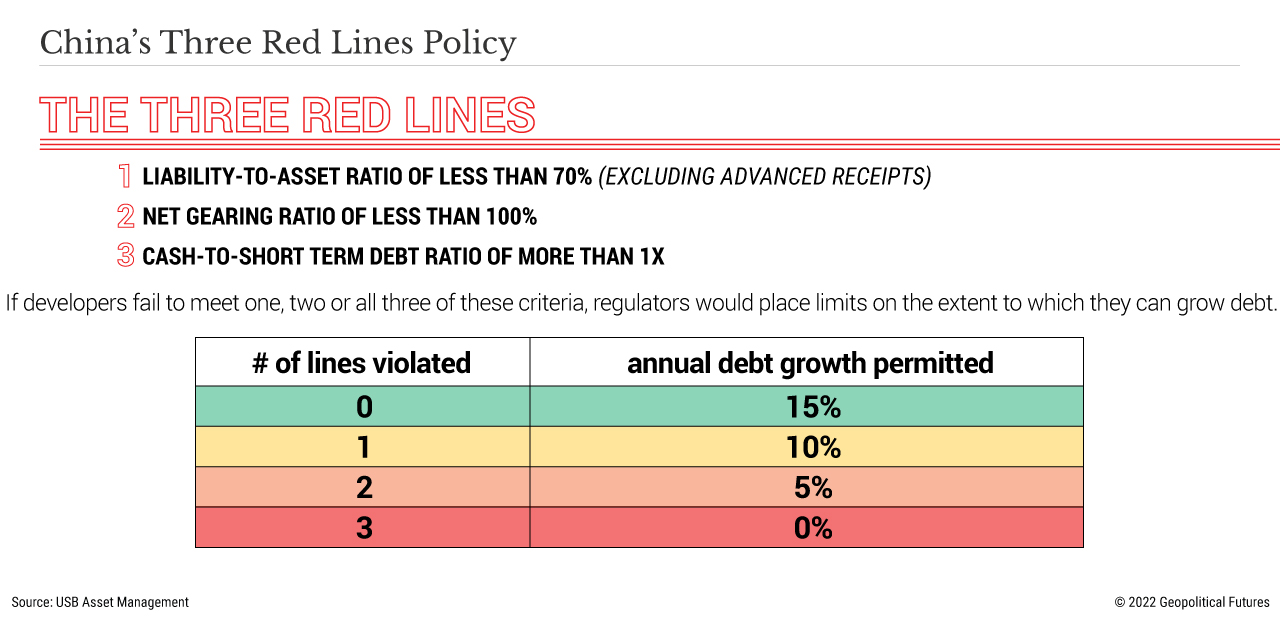

Fearing a bursting of the housing bubble, the People’s Bank of China issued the “three red lines” policy, an ambitious set of reforms intended to improve the financial health of the sector by reducing developers’ leverage, improving debt coverage and increasing liquidity. In 2020, the first year of the reforms, most companies saw improvements in their asset-liability and debt ratios. However, as can be expected with new policies, there have been some side effects. For example, some firms increased their use of minority interests and joint ventures, enabling them to increase leverage through a subsidiary and net the equity value in their balance sheets. This reduced the transparency of the financial statements but did not reduce leverage. Also, with limits on the amount of debt companies could raise, their freely available cash levels and overall liquidity sources were decreasing, which could weaken a company’s ability to weather short-term crises.

The main reason the three red lines policy didn’t work as hoped is that it was too little too late. Because of China’s constant focus on maintaining the previous years’ growth rates, the country risked introducing reforms only when it appeared critical. Unfortunately for Beijing, it was the three red lines that triggered the current property market crisis.

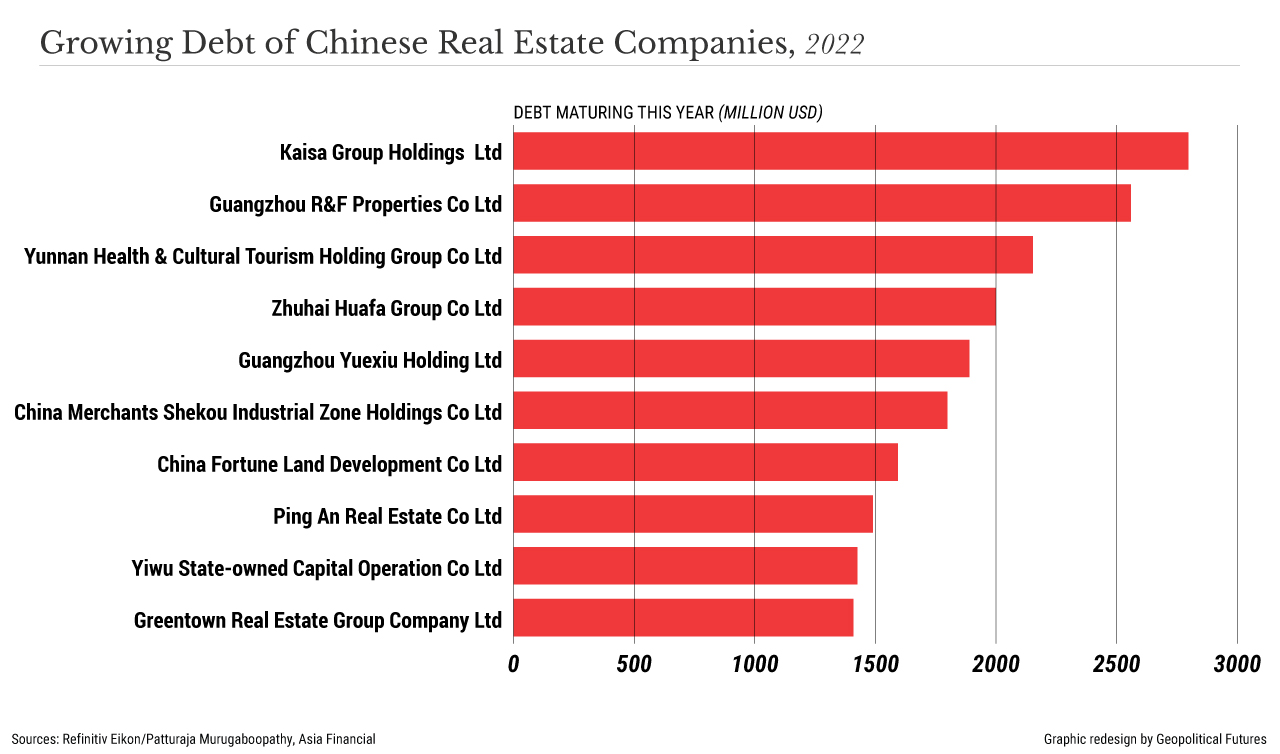

It hit the headlines in December 2021: China Evergrande Group, one of the country’s largest property developers, was formally declared to be in default. Despite the government’s initial assurances that Evergrande was isolated and correctable, more cracks in the foundation soon appeared. At the beginning of March 2022, trading was abruptly halted for shares of Evergrande and two of its units on the Hong Kong stock exchange. The company said it and its units would not publish their annual financial results before the end-of-March deadline due to a comprehensive restructuring. The results still have not been published, and although Evergrande said its restructuring was on track, this has naturally raised further questions and concerns about the true size of the company’s debt.

The bigger problem facing the Chinese government is that the debt crisis is not at all confined to Evergrande. Since late November 2021, several other real estate developers have shown signs of trouble or, like Evergrande, even defaulted. International auditors are resigning from China’s heavily indebted property developers as uncertainty grows about the scale of the crisis. Fears of hidden debt have sent some developers’ bonds plunging, even those that were previously deemed safe. This resulted in a severe loss for China: Last year’s defaults on offshore bonds from Chinese borrowers set an annual record, with the real estate sector making up about one-third of the missed payments. Every event taking place now within China’s real estate sector is compounding the crisis, making it increasingly difficult to solve.

Too Big To Fail

Despite the alarm bells from the real estate sector, the Chinese government’s emphasis on stability and short-term growth has so far taken precedence over making more extensive real estate reforms. The principal reason for this is that the solutions to the real estate problems in the short term pose a huge risk of destabilizing the economy, which could threaten the Communist Party’s authority. In theory, property tax reform would correct the market distortion by disincentivizing real estate speculation and raising revenues for local governments. At the National People’s Congress on March 5, a comprehensive property tax plan was in fact rolled out as one of the main targets of the common prosperity program, topped with the slogan “houses are for living, not for speculation.” However, party elites criticized the plan, arguing that since many party members owned more than one property, the tax would burden them disproportionately and affect social stability.

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s property market reforms also did not align with the interests of senior local officials, whose priorities are generating economic growth, securing government budgets and preventing social chaos in their regions. Even though Finance Minister Liu Kun called for implementing and deepening the package of reforms at the beginning of the year, it has recently been announced by the Chinese Finance Ministry that the trial property tax reforms that are currently in effect in 10 cities would not be extended to more cities. Maintaining high employment and social stability and reducing the harm to loyal investors are too important for Beijing to risk.

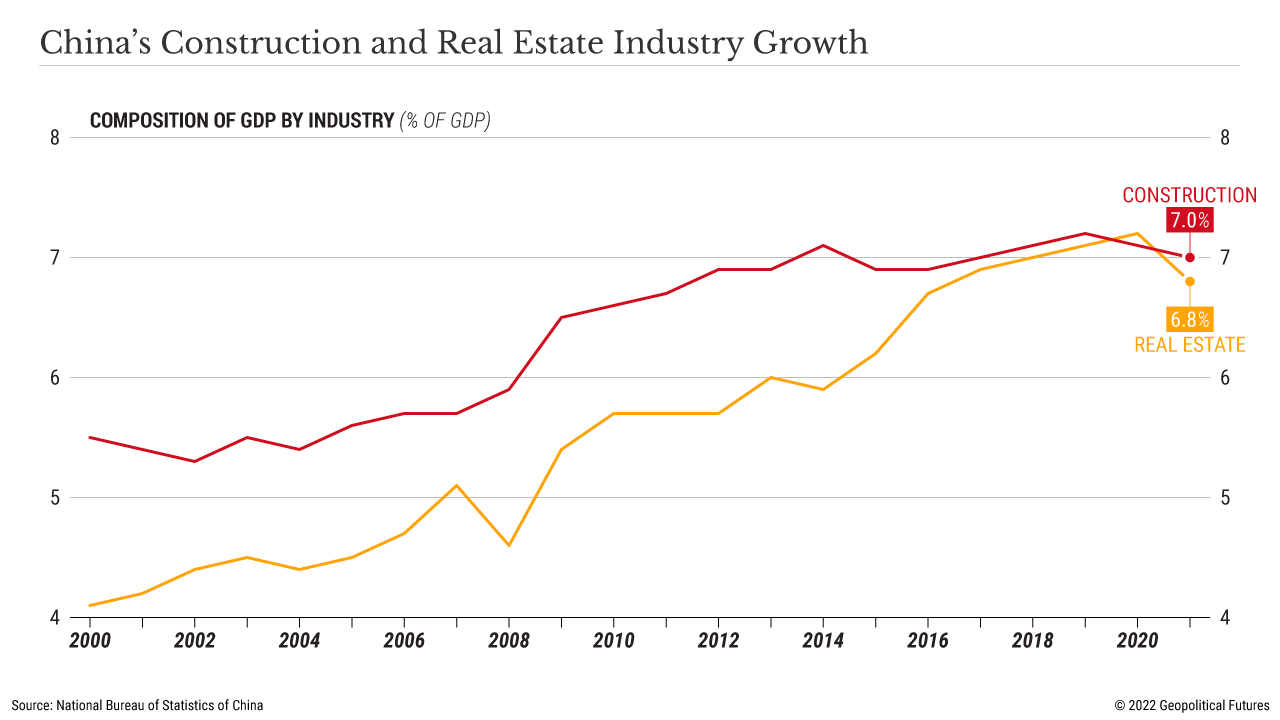

Construction accounts for about 16 percent of urban employment in China. A collapse in the industry would leave about 5.5 percent of China’s population, without work. Already, a sudden rise in unemployment – to 5.5 percent in February from 4.9 percent in October – is almost certain to seriously impact social stability. It also won’t help narrow the wealth gap. Moreover, 30 percent of Chinese bank lending goes to housing construction, and at least 60 percent of bank loans are backed by property as collateral. Therefore, if the property market collapses, China will experience a full-blown financial crisis, which could undermine regime stability and have serious consequences for the global economy.

China still has options to regulate the issue, even in its current state. Some positive changes are already taking place: Chinese banks are finally ready to soften up the three red lines policy to provide safe landing for the several real estate companies that are in trouble or have already defaulted. Also, the government is encouraging mergers and acquisitions in the real estate development sector, with larger, generally state-owned developers likely to take over financially weaker players perceived to have leveraged their connections to local governments to gorge themselves on debt. But rather than a few minor policies here and there, the scale of the problem will probably require a well-timed, well-coordinated chain of shock reforms – which is nowhere in sight right now.

Despite many red flags pointing to a full-scale economic crisis, China is keeping to its common prosperity initiative, implementing only policies that align with the growth objectives included in the current five-year plan. Those objectives are intended to help maintain domestic order and political stability. According to the current plan and the “China Vision 2035” proposal, China hopes to become a “moderately developed economy” – defined as an increase in gross domestic product per capita to $30,000 – by 2035. Even if harsh reforms significantly lowered growth rates for a few years, that would still be a reasonable goal, whereas it could take the country decades to recover from a total economic crisis. For China, there will probably not be a better time than now to reconsider its priorities.