Home Press Room

Press Room

US Bargaining With China and Russia

With the arrival of the second Trump administration, great power competition is at an inflection point. Both Russia and China face internal crises that compel them to engage with the United States. To increase their leverage, Beijing and Moscow are attempting to coordinate their efforts. However, their ability to support each other is severely limited, giving the U.S. considerable room to maneuver.

In recent days, the leaders of the world’s three great powers have engaged in a flurry of diplomacy. A few days before his inauguration, Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping held a phone call that both sides described as positive. Then, hours after taking the oath of office, Trump told reporters that Russian President Vladimir Putin was “destroying Russia by not making a deal [on Ukraine]” and that Russia was “in big trouble” given the state of its economy. Finally, on Jan. 22, Putin held a 95-minute video call with Xi, during which they discussed their interactions with the new Trump administration.

World leaders are typically quick to engage any new administration in Washington, although it’s uncommon for these interactions to occur even before the inauguration. However, this moment is different for two key reasons. First, Trump’s political comeback heralds a campaign to reshape the U.S. political system and overhaul U.S. foreign policy. Second, the world is beset by a level of crisis not seen since World War II.

The United States is managing two wars – in Europe and the Middle East – while confronting the potential for a third in East Asia. China’s economy is in steep decline, forcing Beijing to focus on stabilization. And Russia needs a resolution to its extremely costly war against Ukraine. In essence, all three powers are under immense pressure to deescalate and stabilize their geopolitical positions.

The common thread for China and Russia is that they both need to make a deal with the U.S. to solve their respective crises. Each recognizes the limits of what the other can do to help. Beijing is not in a position to aid Moscow’s war effort in Ukraine, while the Kremlin cannot help the Chinese Communist Party fix its economic problems – which are increasingly becoming political in nature. Both see their best paths forward as reaching agreements with Washington.

Russia hopes to leverage Trump’s pledge to end “forever wars” and his proclivity for dealmaking to retain as much Ukrainian territory as possible after nearly three years of conflict. Similarly, Xi hopes to convince Trump to offer some relief from U.S. restrictions on trade, technology and investment, which could help stabilize China’s faltering economy.

Though in some ways the second Trump administration presents opportunities for both China and Russia, Trump’s unpredictability and the looming threat of punitive measures mean that bargaining will be difficult, to say the least. This uncertainty was underscored by Sergei Ryabkov, the Kremlin’s top official for arms control and relations with the U.S., who warned on Jan. 22 that the window for a deal is narrow and that Moscow lacks clarity on Washington’s intentions. Similarly, Chinese Vice President Han Zheng acknowledged after meeting with his U.S. counterpart, JD Vance, that while there is potential for cooperation, significant disagreements remain.

The lengthy video call between Xi and Putin signals a recognition of their shared reality. The leaders are said to have compared notes on how they see the U.S. behaving in this new era. But setting aside their tireless rhetoric about their strong bilateral friendship, both leaders are wary that a deal between one of them and Washington could harm the other’s interests. Therefore, in addition to coordination, their call was also intended to assess how far the other was willing to compromise.

From the U.S. perspective, negotiations with Russia have a clearer path, given Washington’s interest in ending the Russia-Ukraine war. The key question is how much of Ukraine’s territory Washington is willing to let Moscow retain in a ceasefire. Talks with China are far less straightforward due to the complexities of the geoeconomic relationship. In both cases, however, Washington holds significant leverage, knowing that both Beijing and Moscow have no choice but to engage.

American Naval Policy and China

Editor’s note: If it feels as though the world is changing, that’s because it is. Global economic reconfiguration, demographic decline and geopolitical realignment have fundamentally altered long-held conventional political wisdom, perhaps nowhere more markedly than in the United States. Like all countries, the U.S. is mutable. But unlike most others, changes there have global consequences. The situation in America signals a break in the natural process of a country. America has surprised the world many times, and it is doing so again. The following essay is the third in a series by George Friedman seeking to explain why that’s the case.

Though U.S.-China naval tensions are by no means a new development, they are vital to any understanding of American behavior on the global stage.

Partly this is because the United States is one of the most well-protected countries in the world. It is situated firmly in the middle of North America – a vast landmass buttressed by oceans – and, as such, cannot be readily attacked from the ground. The northern approach to the United States is from Canada, and the southern approach is from Mexico. Neither has the social or military power to invade the United States. The biggest threats to America have always come from the seas. U.S. intervention in both world wars was designed to block Germany from building a fleet that could threaten U.S. maritime power (as the U-boats had in both conflicts). During World War II, the naval effort dwarfed the ground effort until the war was well underway. But the invasion of Europe and the isolation of Japan were both naval actions.

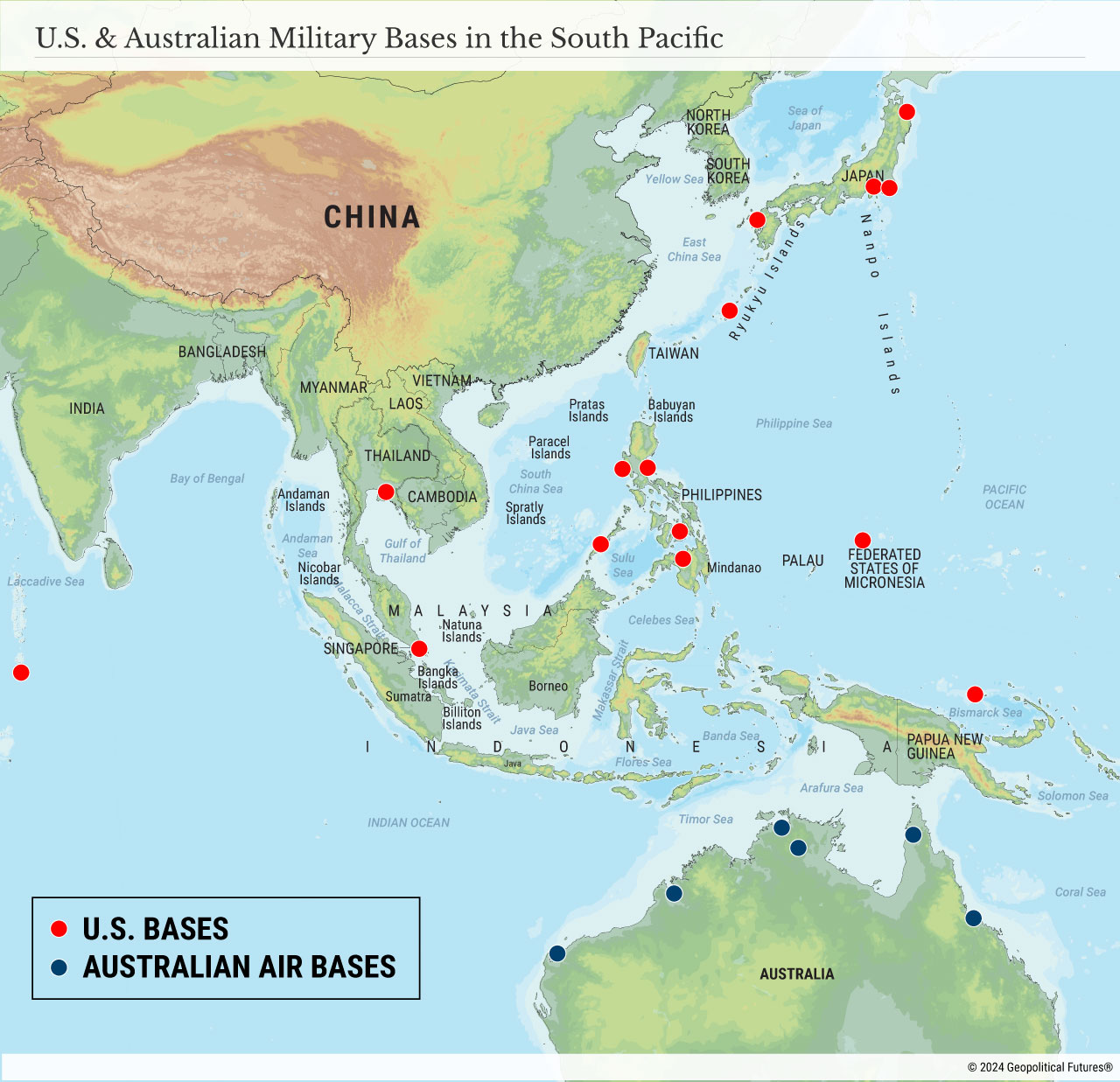

China’s geography differs dramatically. Its east coast, large though it may be, is hemmed in by island chains. These chains, which include sovereign states as well as disputed territories, are a blessing and a curse: They can hinder the maritime trade on which China’s economy relies, but they can also, if prepared and powered sufficiently, interdict U.S. naval forces, even to the point of controlling the seas between China and the United States. Washington’s fundamental interest is preventing this from happening, so it has developed the capability to deploy fleets to block China’s access to the sea. So far, this limited action has satisfied U.S. interests; the Chinese navy has not sortied en masse to challenge the U.S., and U.S. allies, particularly Australia, strengthen its position in the South China Sea. Even so, as was the case in both world wars, the ability to hold the Pacific is critical. (It was Japan’s attempts to employ this same strategy that led to the bombing of Pearl Harbor.)

Beijing naturally feels threatened by U.S. naval power because the United States has the ability to interdict and close Chinese shipping. And because China’s economy is fueled by exports, the threat of interdiction is perhaps the single most animating factor in its strategic policy. Beijing must mitigate the threat by forcing the U.S. Navy back into the Pacific, if not farther. So far, these threats have not amounted to physical conflict. China has been cautious in challenging the U.S. Navy, and the U.S. Navy is cautious in not forcing China’s hand.

To be sure, focusing solely on naval warfare ignores the threats that nuclear bombs and other weapons of mass destruction pose. But the nuclear threat is limited by the principle of mutual assured destruction, and the other, advanced technological threats have not yet materialized on a large enough scale to endanger a continental power. So at this time, the balance of power in the Pacific between U.S. and Chinese naval forces remains key to American hegemony and the alliance that upholds it. In the event of war, the more extreme and technological threats remain secondary to the conventional naval threat the U.S. poses to China and China poses to the U.S. It would be wise to remember this as the Chinese navy develops and as the U.S. Navy potentially weakens.

Though U.S. President Donald Trump’s second term is officially only two days old, it seems as though he wants to maintain some elasticity in his foreign policy – which makes sense. But at some point, he will find himself focused on direct threats, however distant, that will require more rigid responses. U.S.-China relations frequently revolve around marginal issues because neither side is spoiling for a fight. U.S. policy must focus on maintaining that balance.

Europe: The Agony and Ecstasy of US Relations

One of the most pressing geopolitical issues Europe faces is its evolving relationship with the United States. This relationship will be critical as Europe navigates a complex geopolitical landscape shaped by two interrelated dynamics, over which Europe itself has little control: Washington’s stance toward Russia, particularly with regard to the war in Ukraine, and the nature of U.S.-China relations. Together, these factors will significantly impact European stability, security and autonomy.

To be sure, Europe has no shortage of challenges. There has been a marked increase in radical and populist political parties – right and left – that have aggravated an already fractured political landscape. Many of these groups have adopted a more conciliatory stance toward Russia, thus undermining collective efforts to maintain sanctions and to fully support Kyiv. Domestic criticism over Israel’s actions in Gaza remains, as does the general uncertainty surrounding the new balance of power in the Middle East. (The associated discontent over northbound migration is also a major source of concern.) And this is to say nothing of the instability in the European periphery – in the Balkans, in the Caucasus, in Moldova, across the Mediterranean and elsewhere. In this politically charged environment, Europe faces mounting pressure to reconcile its internal instabilities with its external obligations. The interplay of rising populism, economic discontent and foreign policy challenges underscores the fragility of European unity.

But the war in Ukraine stands alone in its ability to impact European politics, security and economic affairs. Yet it is the United States, not Europe itself, that seems to hold the keys to locking the conflict down. The level of U.S. commitment to Ukraine, then, will be a decisive factor in determining Europe’s strategic direction, especially as a new president takes office with a self-proclaimed mandate to end the war.

Either way, the U.S. will have to deal with Russia. Russia’s strategic imperative in the conflict, however, is more than a matter of territorial ambition. Sure, controlling Ukrainian territory achieves certain tactical objectives, but they are secondary to the broader goal of limiting U.S. influence in Europe and expanding Russia's own. For Moscow, pushing the U.S. out of Europe would be a major geopolitical victory because it would allow Russia to better align the Continent’s security and political order with its interests. Winning the war in Ukraine would, in theory, contribute to this goal. The problem is that Russia has not won the war; if anything, it has been significantly weakened by it.

Despite these challenges, Russia has shown a desire to discuss the stalemate directly with Washington. This is a deliberate strategy to bypass Ukraine and European powers. By sidelining them, Russia can undermine their agency and position itself as a primary negotiator on European security. This approach reflects its broader ambition of redefining power relations on the Continent, even as its current position remains compromised by its faltering campaign in Ukraine.

For Europe, this adds another layer of complexity to its strategic calculations. European leaders must navigate not only the immediate challenges of supporting Ukraine and managing the fallout of the war but also the broader implications of Russia’s long-term objectives. The outcome of this dynamic – whether through negotiations or continued conflict – will significantly influence the balance of power in Europe and its relationship with both the U.S. and Russia.

Meanwhile, the relationship between the U.S. and China looms large over Europe’s policy landscape. If tensions between the U.S. and China escalate – whether through economic decoupling, technological rivalry, or intensified security competition in the Indo-Pacific – Europe risks being caught in the geopolitical crossfire. Intensified U.S.-China tensions would not only strain European economies but also affect Sino-Russian relations and thus the outcome of the Ukraine war.

The prospect is already casting a shadow over much of the Continent. Beijing’s strategic interest in Europe revolves around preserving its access to the EU’s common market, a critical pillar of its economic ambitions and global influence. This priority underpins China’s efforts to cultivate bilateral relationships with specific European member states in an effort to undermine EU unity and prevent collective action that might restrict its market access. By offering economic incentives such as investments and trade deals, China has successfully forged closer ties with countries such as Hungary, Greece and others that are strategically significant, economically, politically or otherwise. In simple terms, to weaken Europe's cohesion is to weaken its leverage in negotiations.

At the same time, China has expanded its investments in European port infrastructure, including ports in countries that border the EU. These investments are part of a broader strategy to secure physical access to the European market and establish economic dependencies with peripheral states. By controlling key nodes in Europe’s supply chain, China can ensure it has uninterrupted access to trade and increase its political leverage over countries that benefit from Chinese investment.

China’s positioning in the Ukraine war reflects this strategic calculus. By presenting itself as neutral, Beijing avoids alienating the EU. By maintaining ties with Russia, it hedges its bets while benefiting from Russia’s international isolation. This delicate approach is driven by the need to avoid secondary sanctions that could harm China’s economy, particularly as it anticipates the possibility of increased U.S. tariffs on its exports. Beijing’s overriding goal is to prevent a united Western front that could threaten its economic stability. As U.S.-China tensions escalate, Europe remains a key battleground for influence.

China and Russia both rely on European disunity and fragmentation to advance their strategic objectives, recognizing that a divided Europe is less capable of collective action and more vulnerable to external influence. Russia exploits internal divisions through energy dependencies, information campaigns and direct political interference. China employs economic tools such as targeted investments, bilateral trade agreements and infrastructure projects to establish dependencies. Though their methods differ, they share a common goal: diminishing U.S. influence on the Continent, limiting NATO’s effectiveness and, ideally, reshaping Europe’s political and economic landscape to serve their own needs.

This is why it’s so important to monitor U.S.-European relations going forward. While the trans-Atlantic partnership remains a cornerstone of European stability, there is increased recognition in Europe of the need to pursue greater self-reliance in areas such as defense, energy security and technological innovation. The degree to which Europe can do so – while consolidating its position and resisting external attempts to exploit its divisions – will determine whether it emerges as a more unified and independent actor on the global stage. And how the U.S. responds to these efforts – whether by reinforcing its commitment to European security or recalibrating its approach – will shape the future of the trans-Atlantic relationship and its role in countering the influence of external powers like China and Russia. In this way, the U.S.-European relationship will become as much a source of strength as it is a point of tension.

Daily Memo: NATO's Expanding Presence in the Baltic Sea

New initiative. NATO will launch a new mission to protect critical infrastructure around the Baltic Sea following the recent suspected sabotage of undersea cables in the area, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte announced at a meeting of Baltic allies in Helsinki on Tuesday. The alliance will increase its presence in the Baltic Sea, including through the deployment of frigates, maritime patrol aircraft and new technologies like naval drones.

Armenian backlash. Armenia’s Foreign Ministry summoned Russia’s ambassador to Yerevan, Sergey Kopyrkin, over claims made on a broadcast on Russian state TV. According to Armenia’s public radio, the ministry accused the program of making “artificially generated statements against the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Republic of Armenia.” This comes as Armenia and the U.S. signed on Tuesday a “strategic partnership commission charter” during the Armenian foreign minister’s trip to Washington. Also on Tuesday, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said the Armenian foreign minister had been invited to visit Russia and that a meeting could take place in the near future.

Getting closer. Hamas has begun preparations in anticipation of a prisoner swap deal, Saudi-owned broadcaster Al Hadath reported. According to the outlet, the group has begun separating the hostages it is holding in Gaza into groups and transferring those with U.S. citizenship to “safe places.” A source told the news site that Hamas had demanded international and U.S. guarantees that would force Israel to abide by the terms of a deal before agreeing to a prisoner exchange.

U.S.-Israel talks. Relatedly, the commander of U.S. Central Command, Gen. Erik Kurilla, was in Israel this week to meet with the chief of staff of the Israel Defense Forces. They discussed the situation in the Middle East and bilateral cooperation.

Russia's Africa connections. Central African Republic President Faustin-Archange Touadera arrived in Moscow on Wednesday for an official visit. He is expected to meet with President Vladimir Putin and discuss with Russian officials cooperation on economics, security and humanitarian issues.

China's Africa connections. Niger’s Ministry of National Defense and WAPCO-Niger, a subsidiary of China National Petroleum Corporation, signed on Tuesday an agreement aimed at strengthening security of the country’s oil infrastructure. The deal comes amid increased attacks on a pipeline critical to the export of Nigerien oil.

Relationship reset. British Prime Minister Keir Starmer and Iraqi Prime Minister Shia al-Sudani signed a partnership agreement and trade package, worth 12.3 billion British pounds ($15.1 billion), during the latter’s visit to London. They also discussed migration and agreed on principles for a program to return irregular migrants to Iraq.

American Cycles and Uncertainty

Editor’s note: If it feels as though the world is changing, that’s because it is. Global economic reconfiguration, demographic decline and geopolitical realignment have fundamentally altered long-held conventional political wisdom, perhaps nowhere more markedly than in the United States. Like all countries, the U.S. is mutable. But unlike most others, changes there have global consequences. The situation in America signals a break in the natural process of a country. America has surprised the world many times, and it is doing so again. The following essay is the second in a series by George Friedman seeking to explain why that’s the case.

Many look from afar at the current political, social and economic turmoil in the United States and see it as a sign of American decline. In my most recent book, "The Storm Before the Calm," my goal was to explain the patterns in the U.S. that look like evidence of weakness but in fact show the country's unique strength through remaking itself.

I write: “American society and the American economy have a rhythm. Every fifty years or so, they go through a painful and wrenching crisis, and in those times it often feels as if the economy were collapsing, and American society with it. Policies that had worked for the previous fifty years stop working, causing significant harm instead. A political and cultural crisis arises, and what had been regarded as common sense is discarded. The political elite insists that there is nothing wrong that couldn’t be solved by more of the same. A large segment of the public, in great pain, disagrees. The old political elite and its outlook on the world is discarded. New values, new policies and new leaders emerge. The new political culture is treated with contempt by the old political elite, who expect to return to power shortly when the public comes to its senses. But only a radically new approach can solve the underlying economic problem. The problem is solved over time, and a new common sense is put into place, and America flourishes – until it is time for the next economic and social crisis and the next cycle.”

It has been nearly 50 years since the last cyclical transition occurred. In 1981, Ronald Reagan replaced Jimmy Carter as president, changing the economic policy, the political elites and the common sense that had dominated the country for the 50 years since Franklin D. Roosevelt replaced Herbert Hoover.

The 2020s have brought the convergence of two major crises: the institutional breakdown of a federal government desperate to preserve its position (while failing to function effectively) and the collapse of once-successful social and economic systems. Both systems, quite crucial in the past, are no longer serving their purpose, leaving instability and disorder in their wake. These crises often come to be personified by certain individuals. From the standpoint of the model in my book, Donald Trump exploited the crises in the elections of 2016 and 2024 to side with those who suffered the most economically and those who doubted the experts. Joe Biden and Kamala Harris sided with those who saw themselves as incurring less cost and social pain and those who trusted the federal government. Each side held the other in contempt. Those who resisted were portrayed as ignorant, and those suffering economically and socially were seen simply as paying the price necessary to protect themselves. Those who doubted this perspective were deemed at least irresponsible.

On the other hand, those who accepted the technocratic solution of the medical establishment during the COVID-19 pandemic were unaware of the hidden intentions of those who advocated the solution, or at least unaware of the limits of their knowledge. They were trapped in the systematic lies. The idea that reasonable people could disagree was completely absent. All disagreement was seen as either idiotic or monstrous.

Not all of Trump’s supporters agreed with his views, nor did all of Biden’s and Harris’ supporters agree with theirs. But the dynamic was driven by passion, which itself was driven by the social, economic and institutional tensions tearing at the country’s fabric. The next phase of a cyclical shift is what might be called pseudo-normalization. As my book predicted, the next president after Trump’s first term was a Democrat. This was not because the shift depended on party politics. Following the election of a disruptive president, and stunned by the political disruption, the political system would seek to stabilize itself without fundamental economic or social shifts. In other words, it would seek to return to a stable norm.

In the last 50-year cycle (1930 to 1980), the political chaos of the Nixon years – which really began with the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson – was followed by the presidencies of Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter. Each sought to normalize the system. As Ford put it after pardoning Nixon: “The long national nightmare is over.” Indeed, the political nightmare was over, in the sense that Ford and Carter were both operating within the behavioral norms that were personified by John F. Kennedy, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Harry S. Truman and Franklin D. Roosevelt. This was possible because they all shared core beliefs: assertive foreign policies, supporting social security, federal responsibility for economic performance and racial integration. In other words, they shared key principles that were forged during Roosevelt’s first term to replace the then-failed policies of the previous era.

When Nixon became president, many of those policies were failing. The Vietnam War called into question an assertive foreign policy. The economic system was beginning to produce results that were unacceptable from the standpoint of a New Dealer. Despite the passage of the Civil Rights Act, Black Americans were still on unequal social and economic footing with their white counterparts. The Roosevelt era, which in a sense was drawing to a close with Johnson’s Great Society, ended when Nixon was forced to impose a national compulsory wage and price freeze to control the first surge in inflation.

The underlying problem was economic and social. The Roosevelt-era model saw the fundamental problem as a lack of demand for goods that had to be solved by funneling money to the industrial working class, which had been the most victimized class in the Great Depression. The tax code and other tools were created to achieve higher consumption. Over time, higher consumption lowered available investment capital, and industry became less efficient, less innovative and less able to compete on the global market. Nixon said “we are all Keynesians” and intensified the movement of capital for consumption.

The lack of investment capital created an under-invested economy with increased demand that led to rising costs alongside rising demand, which resulted in the massive inflation of the 1970s. This was compounded by the assertive foreign policy that triggered the Arab oil embargo. Inflation lowered consumption, weakened businesses and raised unemployment. The 1970s was a decade of failure.

Ford and Carter sought to return things to normal. The latter sought to offset shortages of investment capital by cutting taxes for the middle and lower classes, which would use the difference to increase purchases and generate economic activity. Carter followed the playbook of the Roosevelt era, but the play didn’t work. Most important, Carter and Ford sought to resurrect the norm in politics, but they could not see that the problem was not at the political level. The industrial working class, poor and struggling with unionization, was no longer the victim or the challenger of the system. Socially, the center of gravity had shifted to the suburban professional class. At the end of a cycle, it is hard to see that everything has changed, so any political stabilization is, at best, temporary. The election of Ronald Reagan bore this out.

The phase after the 2020 U.S. presidential election resembled the Ford-Carter political era. It represented the stabilization of a political period as the economic and social crises intensified. Its intensification was, as usual, made more extreme by the inability of the political system to mitigate or even recognize the tensions.

If the economic tension of the Roosevelt era stemmed from insufficient investment capital, the economic tension of today is a surplus of investment capital and a lack of investment opportunities. As discussed in "The Storm Before the Calm," we are at the stage of maturation of the microchip culture, and this will show itself in two ways. The first is a growing lack of innovative and marketable opportunities. The second is the decline of major firms whose size either makes them unmanageable or exposes them to political pressure.

The industrial working class was supplanted as the center of gravity of society by the suburban professional class, which took power at the beginning of the Reagan era in the 1980s. This shift culminated in the urban technological class (technologists or workers in associated professions), which had a different cultural aesthetic but a similar cultural reality. Like suburban professionals, the urban technologists lived by the production of ideas to solve problems for businesses and individuals. And like the suburban intellectuals, they saw their preeminence as permanently redefining America.

All dominant classes redefine the U.S., but none are permanent. As microchip technology matures, it will of course remain an important part of the nation, but not its entire future. I do not consider artificial intelligence a new technology, but merely the advancement of the same microchip technology. And as competitive economic pressure and the inherent obsolescence of all industries take hold, this class will begin to decline from the pivot point into just another class of aging professionals. That will happen alongside the economic crisis that will crop up as the oldest millennials reach their 50s, recreating the malaise that we saw in the 1970s.

The economic crisis caused by the success of the Reagan era in producing wealth from innovation reversed the changes of the Roosevelt period, in terms of the value of money, but created the same political stress and forced a systemic rotation in innovation and industries. Just as Carter tried to solve the problems caused by the Roosevelt era by the same means as the Roosevelt, so too will the presidents of this decade use Reagan-era solutions to deal with the failures at the end of the Reagan era, focusing on maximizing available capital in a period where the problem is excess money. In the 1970s, a Republican and a Democrat both acted the same way. Partisan politics are irrelevant to historical forces.

If my model is correct, we are facing roughly another four years of this disjuncture between economic and social reality on the one hand and the political system on the other. We have to see if Trump in his second term will be aligned with the era or not. After Nixon came a period of political stability. Most likely a new American era will emerge in 2028, changing the way American society and institutions work. Biden may have brought a semblance of normalcy back to politics, but he was not able to come to grips with the deeper problems. It is not yet certain that Trump will be able to do so, but neither is it very important. It is the 2028 election that will matter, in the same way that 1980 and 1932 did. We must remember this is cyclical, not existential.