Originally produced on April 16, 2018 for Mauldin Economics, LLC

By George Friedman and Xander Snyder

The Russian ruble, Turkish lira, and Iranian rial are all falling in value. What do they have in common? The United States is in some way involved in their decline. It’s a sign of US power: Even as its military becomes more limited and it threatens to pull back from the Middle East and other parts of the world, the US can still put pressure on the economies of countries that are working against US interests and impact global conflicts without resorting to military force.

Sanctions Pressure in Russia

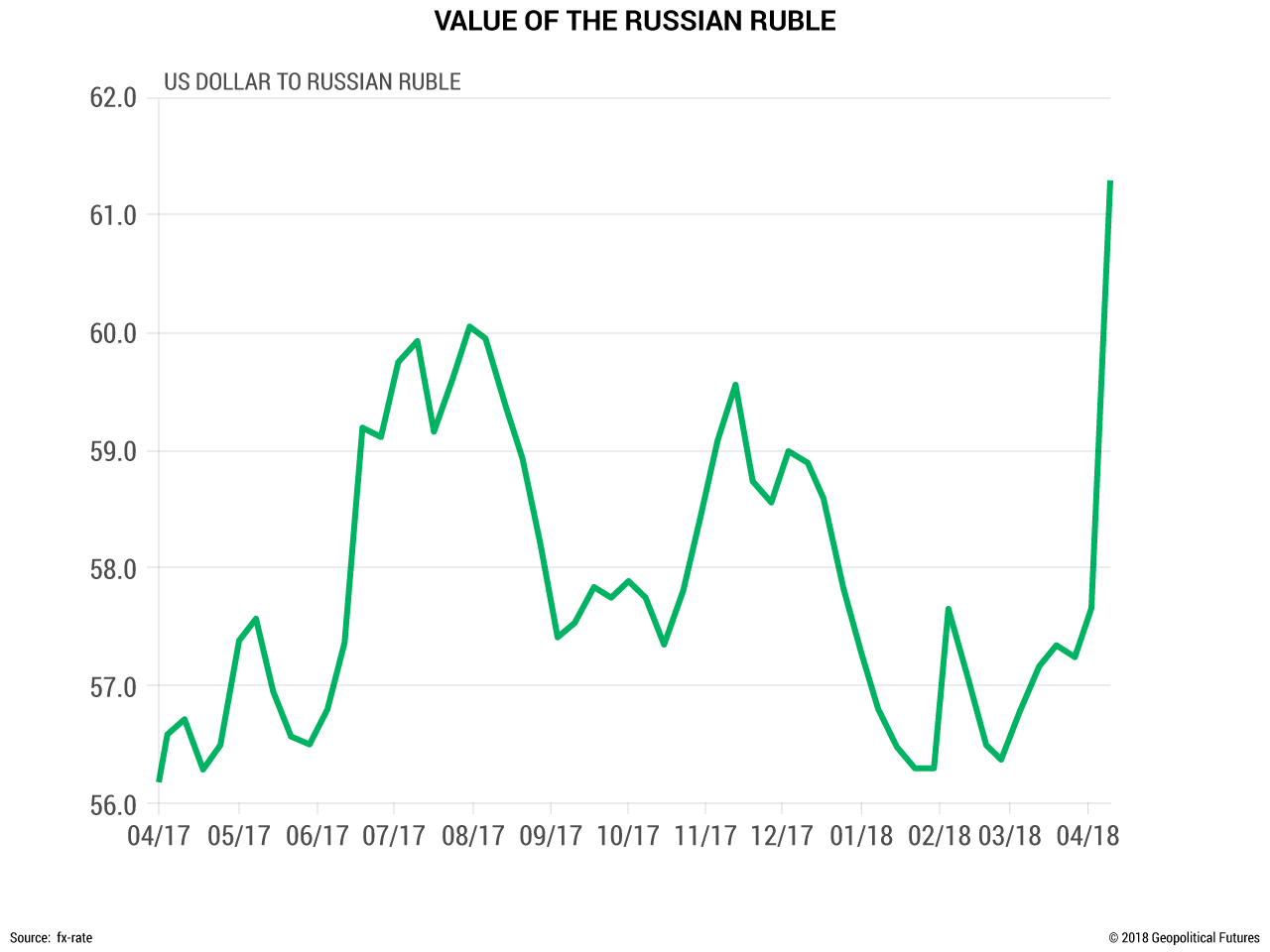

For Russia, recently imposed sanctions and the threat of new sanctions are proving to be a drain on its economy and the ruble. Earlier this month, the US announced a new round of sanctions that target Russian oligarchs and their businesses. Rusal, a metals conglomerate and one of the world’s largest aluminum producers, was hit particularly hard, with its shares declining by nearly 35% in two days. But Rusal wasn’t the only company with ties to the Russian government to experience a rapid sell-off: Sberbank and VTB, two major Russian banks, saw their share prices decline by nearly 20% and 10%, respectively, after the sanctions were announced. Some financial analysts have estimated that up to $16 billion in wealth owned by Russian oligarchs was wiped out in just a couple of hours.

Through the use of so-called secondary sanctions, which target both US and non-US companies that do business with sanctioned Russian companies and individuals, the US is restricting Russia’s access to dollars. This limits Russian companies’ ability to conduct transactions globally in dollars and their access to foreign investment. For example, Rusal has been forced to ask its customers to fulfill contracts in euros rather than dollars. The declining ruble also makes foreign machinery and equipment—which are among Russia’s top imports and which Russia needs to modernize its economy—costlier.

By imposing sanctions, the US wants to make Russia’s domestic problems strong enough to force Moscow to turn its focus inward and limit its foreign adventures. And more sanctions might be on the way. A bill introduced in Congress last week would restrict investment in Russia’s sovereign debt, putting further pressure on the ruble. Washington is thus signaling that it is by no means out of ammunition.

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said the sanctions introduced this month are a response to Russia’s occupation of Crimea and its ongoing support of the Assad regime in Syria. The recent poisoning of a former Russian spy in the United Kingdom also undoubtedly played a role. But the sanctions shouldn’t be seen solely as a reaction to these events. The US is trying to send Russia a broader message: If Moscow keeps asserting itself in places like Ukraine, Syria, and Georgia, it will face consequences. In a way, it’s a proactive move intended to keep the Russians in check and prevent further Russian incursions elsewhere.

Uncertainty in Iran

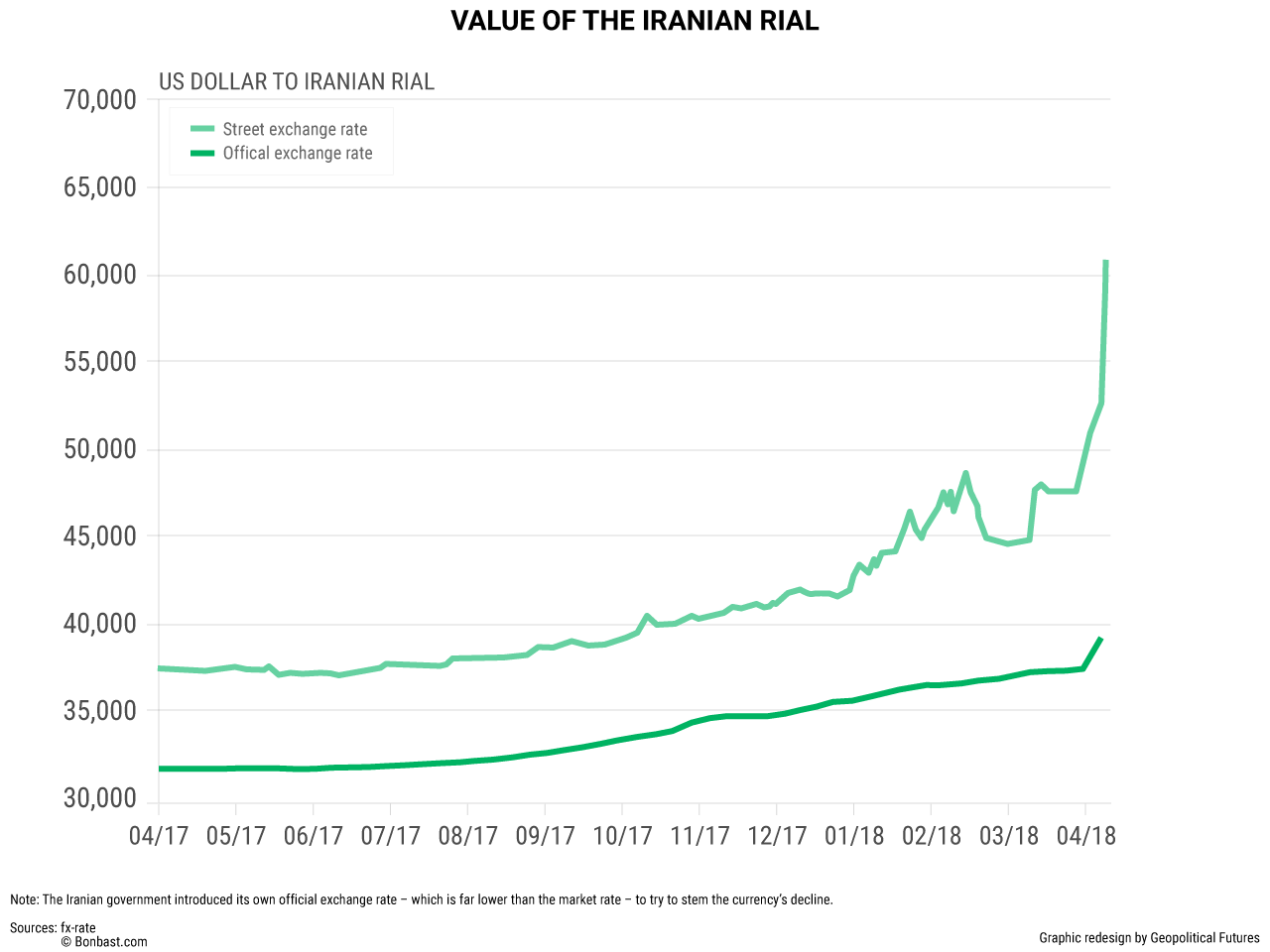

Another adversary that the US faces in Syria is Iran. While the US was busy cobbling together a weak coalition of moderate rebels to fight Bashar al-Assad and the Islamic State, Iran was solidifying its position there. The US now needs a way to limit Iran’s expansion and encouraging the devaluation of the rial—by, say, threatening to scrap the Iran nuclear deal—is one way to do it. The uncertainty surrounding the deal makes it more difficult for foreign companies to conduct business in Iran, limiting its foreign investment potential. The US doesn’t need to actually abandon the deal to make an impact—it just needs to threaten to do so.

That the rial has so sharply declined as a result of this uncertainty is a sign that Iran’s economy remains vulnerable and its security tenuous, regardless of its rising clout in Syria and Iraq. Like Russia, Iran is now forced to turn its attention to domestic issues rather than its efforts at external expansion. For example, the government last week introduced its own exchange rate of 42,000 rials to the dollar—far better than the market rate, which currently hoovers around 60,000 rials to the dollar—to try to stem the currency’s decline.

The large-scale protests in January and the more localized ones in Khuzestan and Isfahan provinces last week indicate that there is consistent and widespread dissatisfaction with the regime. In Isfahan, farmers are again protesting the government’s poor handling of water shortages during a severe, nationwide drought, which has made it difficult if not impossible for farmers to make a living. As a result, fewer crops are being grown domestically, increasing Iran’s need to import food. But with a weaker rial, food imports become more expensive.

One of the catalysts of the January protests was a spike in the price of food staples. Following those protests, Iran—under growing budgetary pressure as it allocates ever more funds to fighting wars—was forced to walk back planned subsidy cuts to appease the public. This forced Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, to dip into Iran’s reserve fund to ensure funding for the military wouldn’t be slashed. But a weaker rial will certainly make the Iranians think twice about their military funding and could impact Iran’s ability to continue waging war at the scale that it has in the past couple of years.

Debt-Fueled Growth in Turkey

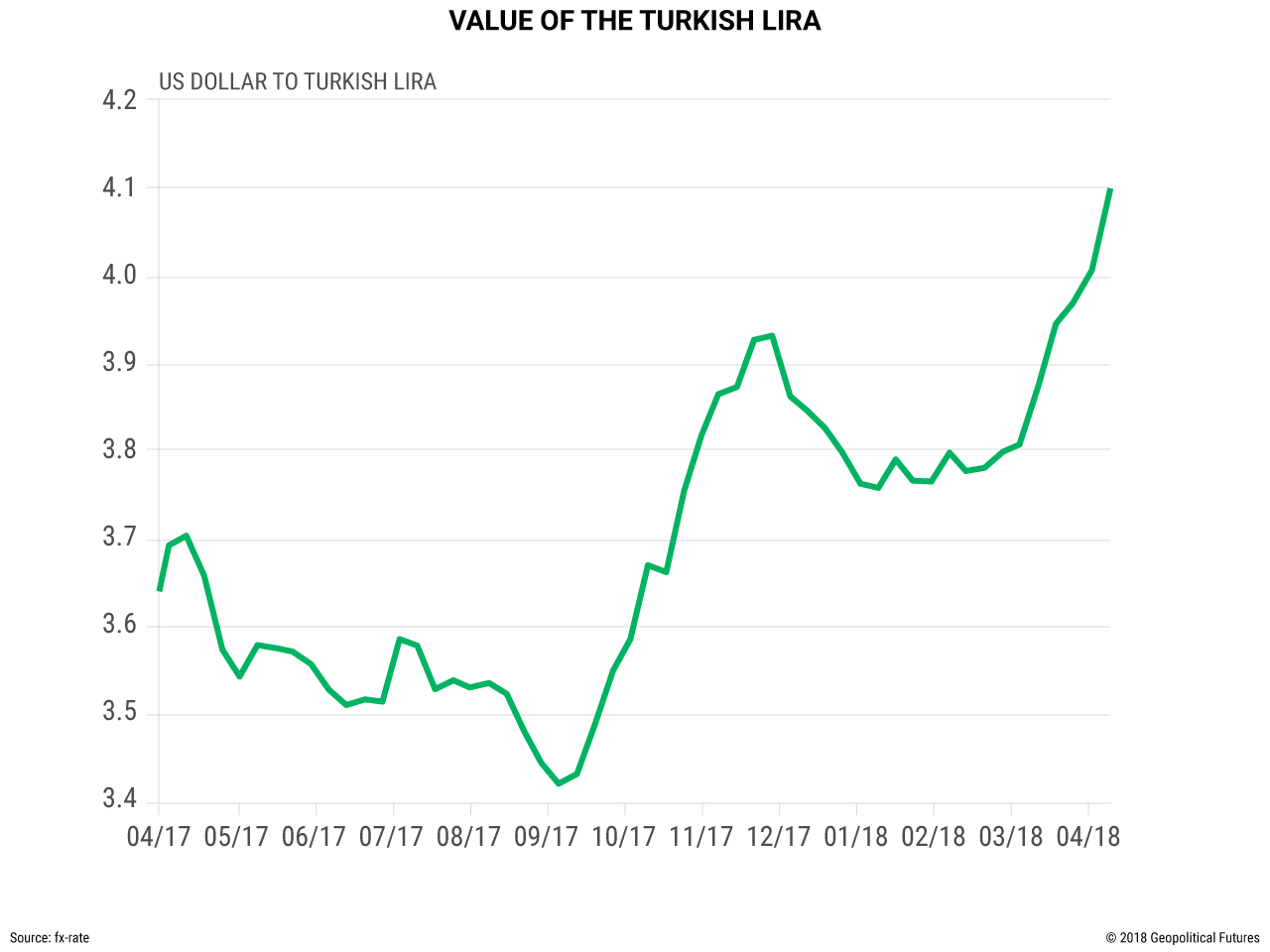

In contrast to Russia and Iran, Turkey isn’t a direct target of the United States. Nevertheless, Turkey faces serious risks due to US monetary policy. In response to a tight US labor market and consistent economic growth, the Federal Reserve has been raising interest rates since 2015 and will almost certainly continue to do so throughout 2018. This encourages capital inflow to the US as investors seek higher returns. It also creates higher demand for the dollar, increasing the dollar’s value relative to other currencies, including the lira.

A weaker lira is a problem because, although Turkey’s economy has seen high levels of growth, it has been supported with external debt (that is, debt denominated in foreign currencies). Accompanying this debt-fueled growth have been rising rates of inflation, which devalue the lira. A weaker lira makes it harder for Turkish businesses to pay back foreign debt. In March, ratings agency Moody’s downgraded Turkey’s sovereign debt, citing a combination of factors including inflation, a weak lira, and the risk of external financing being tabled.

Higher US interest rates, therefore, are a threat to Turkey’s growing economy and thus its ability to expand its reach to places where it might challenge US interests. A weak economy that must dedicate more and more funds to servicing debt will find it progressively more difficult to support the costs of war.

To be clear, the US isn’t intentionally weakening the Turkish economy through its own monetary policy. Rather, the US economy is so large and pervasive that it has far-reaching consequences for countries around the world. That said, the US and Turkey have been at odds over the situation in northern Syria and Washington wouldn’t mind indirectly curtailing Turkey’s ability to expand its operations against Kurdish forces there.

The decline of US power has become a trope in discussions of global affairs. But its ability to contribute to the domestic problems of its adversaries—and an ally with which it is increasingly at odds—is a sign that the US can still exercise substantial soft power, even as its military is overcommitted and limited in its ability to deploy force to new theaters.