For years, Europe has been notoriously slow in developing a coherent strategy for its defense industry. And it never really had a reason to formulate such a plan, so long as the United States guaranteed its safety. But the second Trump administration – specifically, its transactional approach to international affairs and its eagerness to end the Ukraine war – has convinced Europe that it may no longer be able to rely on the United States for its defense needs. Other U.S. allies, including Canada, South Korea, Japan and Australia, are asking themselves the same question, especially in light of the seemingly punitive measures such as tariffs the Trump administration has imposed on them. In this context, many policy changes are underway, perhaps none so important as those in the defense industry.

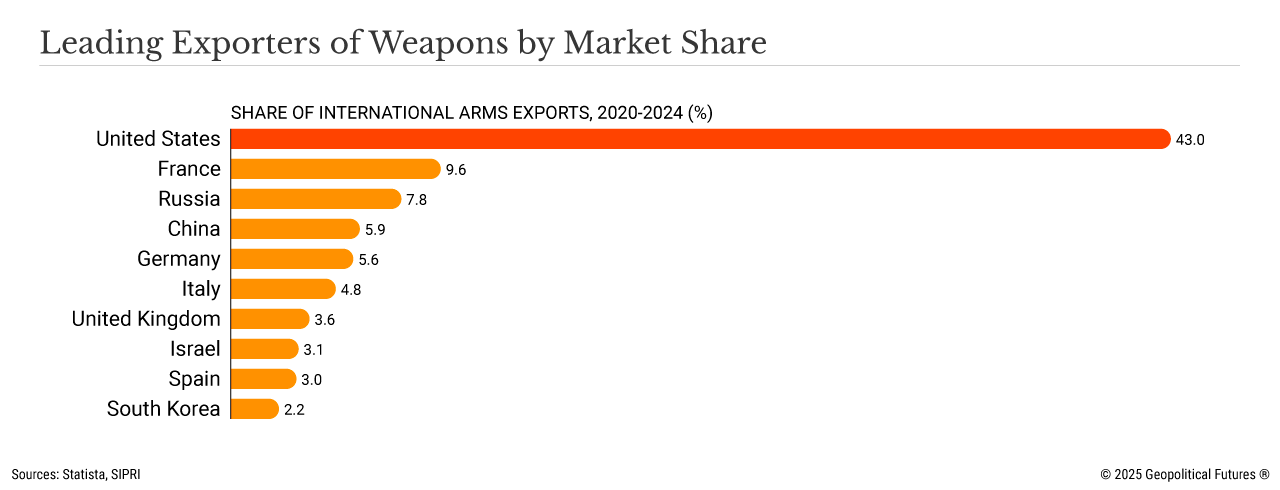

Through NATO, the U.S. has been Europe’s security guarantor since 1949, a position that has been a boon to the U.S. defense industry. In addition to run-of-the-mill global arms sales, companies such as Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Raytheon and Northrop Grumman have become leading defense manufacturers because the weapons systems they produce have become NATO standard. The pressure Washington exerted on European allies to buy American often hampered domestic research and development. When the F-35 and F-16 fighter aircraft, for example, became NATO standards, they depressed demand for European alternatives such as the Eurofighter or Rafale. U.S. firms were thus able to achieve technological superiority through Pentagon R&D funding and, critically, were able to ensure that U.S. makers continuously filled order sheets.

The U.S. economy benefited enormously from this arrangement. NATO commitments and the overall desire to remain the preeminent global power ensured that the U.S. military budget would be massive. In turn, this facilitated the export of expensive, high-value weapons systems. Put simply, the U.S. never didn’t profit from this military-industrial complex. Even during the first Trump administration, the president (rightly) accused NATO members of failing to meet spending requirements (2 percent of gross domestic product), suggesting that the U.S. was getting ripped off. Combined with the war in Ukraine, this accusation led to a steady uptick in European defense purchases, a disproportionately high share of which was sold by the United States.

According to data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, the U.S. has only extended its lead in weapons exports over the past four years. Between 2015 and 2019, it accounted for 35 percent of global weapons exports; from 2020 to 2024, that figure rose to 43 percent. And for the first time since the 1990s, Europe was the number one regional destination for U.S. exports. (The Middle East ranked second.)

Given Washington’s dominant position, it’s striking to U.S. allies that President Donald Trump would accuse them of taking advantage of the United States. This accusation has driven a wedge between the U.S. and its erstwhile allies – as has the willingness of, say, Canada and Mexico to meet Trump’s increasing demands to curb human trafficking and drug smuggling and his administration’s subsequent imposition of tariffs anyway. As have the continued threats to take the semi-autonomous Danish territory of Greenland. And the on-again, off-again tariff threats that have only destabilized markets and undermined confidence in Washington’s capacity as a reliable partner. Indeed, tariffs against otherwise stalwart partners in the U.K. and Australia have forced virtually every U.S. ally to reconsider their positions.

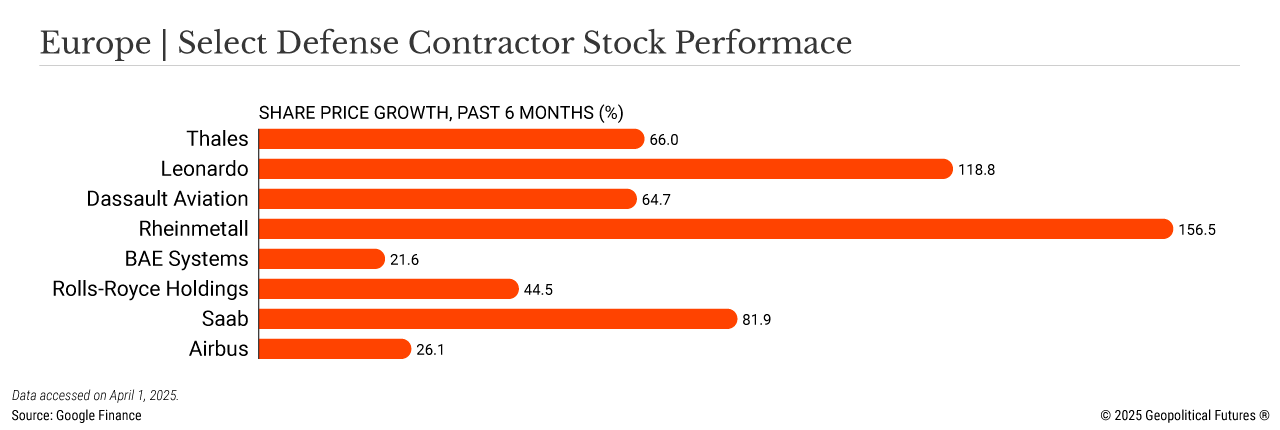

This question is most urgent in Europe, whose defense industry stands to gain the most from the new normal. The Continent has some notable companies able to produce high-quality alternatives to American products, but years of trans-Atlantic shipments have hampered their ability to manufacture at scale. But adversarial U.S. policies, a pressing desire for European self-reliance and a still-unresolved war on Europe’s eastern border will likely breathe new life into the defense sector.

To enable this shift, EU funds have been made available under the Readiness 2030 fund, giving states more flexibility on defense spending. This includes allowing member states to increase their defense spending by 1.5 percent above normal budgetary constraints, freeing 650 billion euros ($700 billion), and making available 150 billion euros under the Security Action for Europe umbrella to “help countries invest in key defense areas like missile defense, drones and cyber security.” Last year, EU members collectively spent roughly 1.9 percent of GDP on defense, but this is set to increase rapidly. NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte recently argued that European military spending should be “north of 3 percent.” The EU is also likely to amend the 392 billion euro regional development fund to boost the defense sector following the midterm review of the 2021-27 program. The new EU commission report purportedly says that more than 90 percent of that fund should be given to the defense sector “without restriction in terms of geography or size of the enterprise.”

The way these changes are playing out is especially interesting in Germany. Recall that, in no uncertain terms, the desire to keep Germany disarmed was one of the primary reasons NATO and the EU were established in the first place. Under Germany’s likely next chancellor, Friedrich Merz, a recent vote allowed defense spending to exceed 1 percent of GDP to overcome what Merz described as a “false sense of security.” This has resulted in the legislative approval of up to 400 billion euros in defense investment over the next decade. This excludes 100 billion euros already committed under an existing special fund to be used by 2027 and 500 billion euros on infrastructure investment that should enhance logistics capabilities.

European defense companies have much to gain from these policy changes, especially since much of the newly available funds must be spent in Europe. These companies’ stocks have already risen accordingly. In France, they include Thales, which focuses on radars, avionics, cybersecurity and defense electronics; MBDA, Europe’s largest missile manufacturer, co-owned by Airbus, BAE Systems and Leonardo; and Dassault Aviation, which builds the Rafale and Mirage fighters. In Germany, they include Rheinmetall, producer of ammunition and the Leopard tank. In the U.K., they include BAE Systems and Rolls-Royce’s defense arm. In Italy, Leonardo, which produces helicopters, fighter aircraft, and defense electronics. And in Sweden, Saab, which manufactures Gripen fighters, submarines and missile systems. Airbus, a multinational firm predominantly owned by France, Germany and Spain, also stands to benefit. It boasts a helicopter and an air and space division that produces military aircraft such as the Eurofighter, A400M Atlas, C295 and CN235 transport and logistics aircraft, Eurodrone and Zephyr drone, Tiger attack helicopters and the NH90, and H225M transport and logistics helicopters, as well as producing and launching military satellites.

Over the past decade, new players – most notably Japan and South Korea, who, as it happens, are U.S. allies – have emerged to try to break into the global defense export market and provide alternatives to the traditional defense industry powerhouses. In South Korea, annual defense exports accounted for only $2 billion-$3 billion before 2020. That number has increased substantially in subsequent years: $7.3 billion in 2021, $17.3 billion in 2022, and $14 billion in 2023. By March 2024, South Korea was among the top 10 largest exporters of major arms. Throughout that year, global arms imports surged, only to rise even higher this year as they are an established alternative supplier to Europe. Notably, South Korea looked like an emerging player even before the U.S. put its allies on notice, given their cheaper and efficient supply chains favored by many countries.

Japan, meanwhile, has for years steadily removed its self-imposed restriction on defense exports. Since then, it has tried to grow its defense industrial base, spending nearly $60 billion in 2024 to do so. Japan is also codeveloping next-generation fighters with the U.K. and Italy under the Global Combat Air Program. All this has resulted in major arms companies expanding their production capacity and growing their order sheets.

Neither Japan nor South Korea has been spared from threats, tariffs or other measures from the Trump administration. Trump himself has criticized what he sees as an asymmetrical U.S.-Japan security treaty, arguing that Tokyo receives disproportionate economic and security benefits from the arrangement. He called South Korea “unfair to the U.S. – militarily and in other ways,” and the country has been put on the “sensitive country” list, a designation set by the Department of Energy for nuclear safety concerns. Both countries are going to be affected by the 25 percent tariff on automobiles and auto parts announced by Trump. These actions have driven Japan and South Korea to try to develop an increasingly friendly trade relationship with China. Previous negotiations surrounding a trilateral free trade agreement that had been frozen for six years, for example, are now set to resume.

Crucially, Japan and South Korea are still extremely reliant on defense imports from Washington. Japan receives more than 90 percent of its defense imports from the U.S., while South Korea receives roughly 84 percent. For this reason, they, like other U.S. allies, will very likely seek alternatives to what they see as an unreliable partner.

Then there is Australia. The U.S. has been Australia’s strongest and most reliable partner since the end of World War II. In 2021, their partnership culminated in the signing of the AUKUS agreement, a 20-year commitment to build U.S. nuclear-powered Virginia-class submarines for about $368 billion. During Trump’s first term, Australia was exempt from aluminum and steel tariffs because the U.S. had a heavy trade surplus with it. This time around, however, there has been no such exemption despite repeated protestations from Australia’s foreign and trade ministers. The mood is therefore much more cautious toward Washington than it was just six months ago. There is a growing concern with AUKUS that the submarines will be deprioritized if the partner countries are unable to manufacture them fast enough to keep up with U.S. demands – a valid concern, given that the production rate is around 1.3 per year, lower than the 2 per year necessary to fulfill backorders.

In addition to the long-term shifts in the defense industry that the Trump administration has caused, there have already been some immediate responses. Canada, which has drawn the most ire from the second Trump administration, has signed a deal with Australia for the development of a new radar system worth $4.2 billion, which will be Australia’s largest-ever defense export. This deal was made possible only by the animosity between Washington and Ottawa.

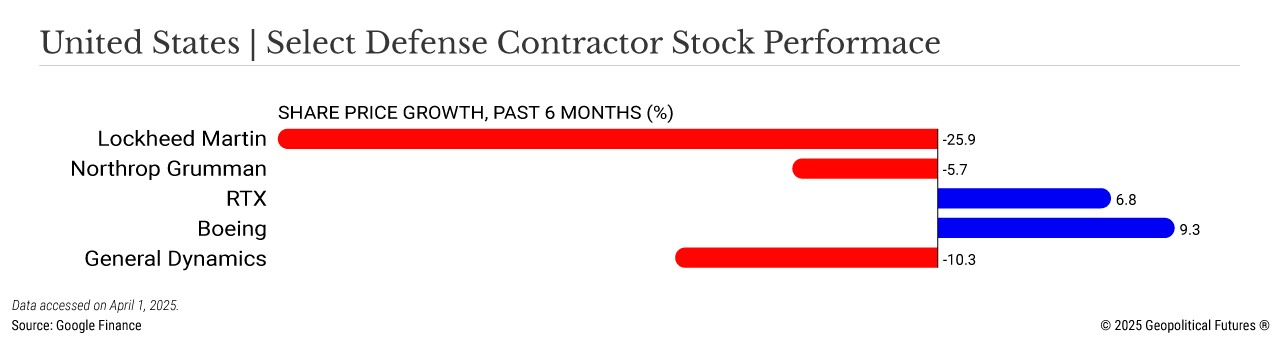

Elsewhere, Portugal and Canada have said they are reconsidering F-35 procurements (which would be a boon for European or South Korean competitors). When asked whether future aircraft sales to allies would be deliberately downgraded, Trump said, “It probably makes sense, because someday, maybe they’re not our allies.” To try to contain the damage, Lockheed Martin has offered new incentives to Canada if it continues with the program. This comes amid speculation around the potential existence of a “kill-switch” on F-35s sold to NATO allies that could shut them off completely. (As a matter of fact, a simple refusal to supply spare parts, maintenance and upgrades would potentially ground a fleet.) This will result in the loss of hundreds of billions of dollars in future defense contracts and associated jobs in America.

To be sure, U.S. arms manufacturers will continue to have some kind of relationship with U.S. partners in the future. Long-term contracts, maintenance and systems compatibilities make it virtually impossible to end these relationships overnight. Over the long term, however, significant damage has been done to the reputation of U.S. partnerships, and buyers will be far more wary of business dealings with Washington, especially if doing business requires a de facto dependence on U.S. exports.

Their wariness will likely outlast Trump. The idea that U.S. policy could be so fickle is bound to make allies think twice before buying from the U.S. If the days of bipartisan support for U.S. military dominance are indeed gone, erstwhile European, Australian, Asian and North American allies will not just eschew U.S. sellers. They will want a piece of the pie for themselves, and they will compete with one another to get it.

America in Transition &

America in Transition &