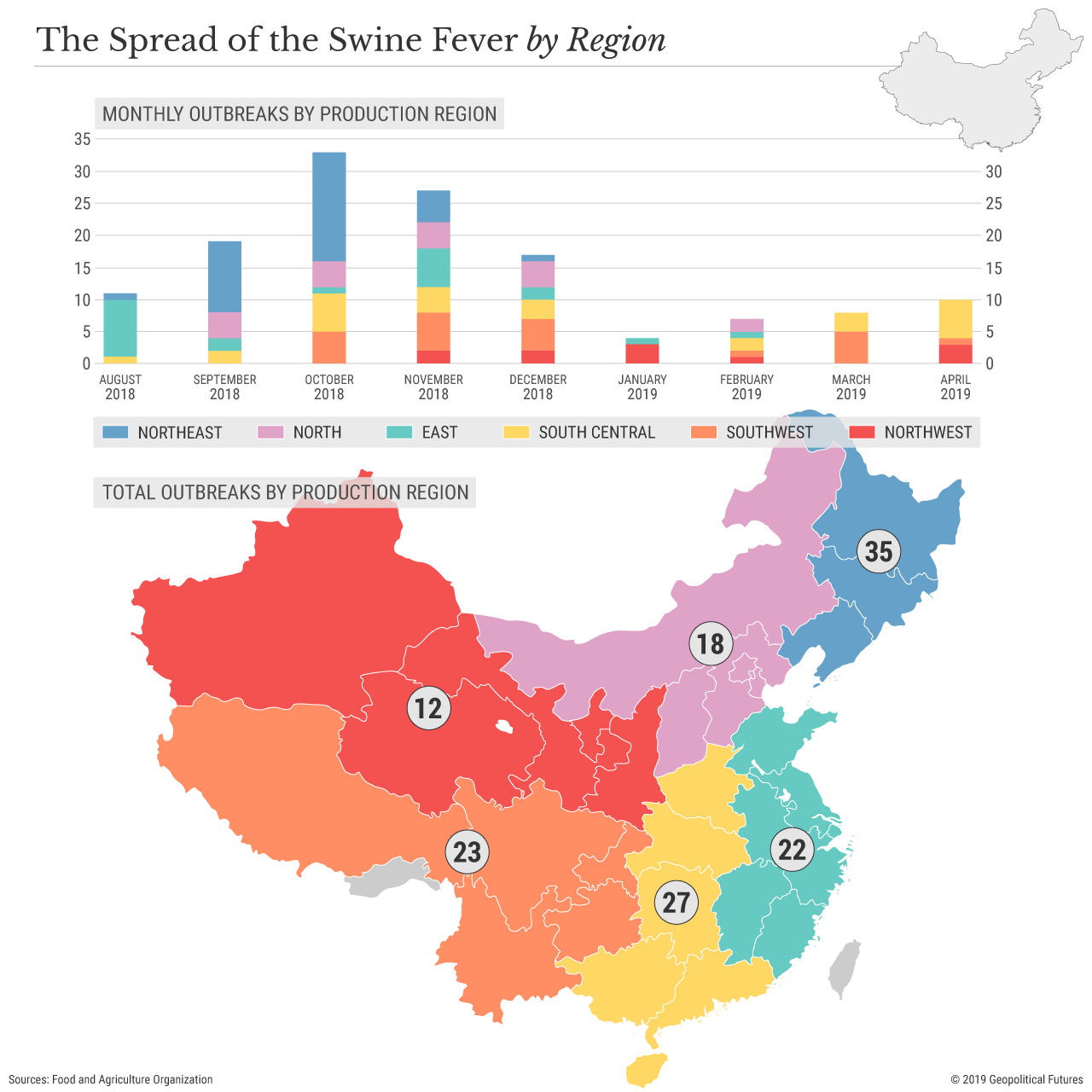

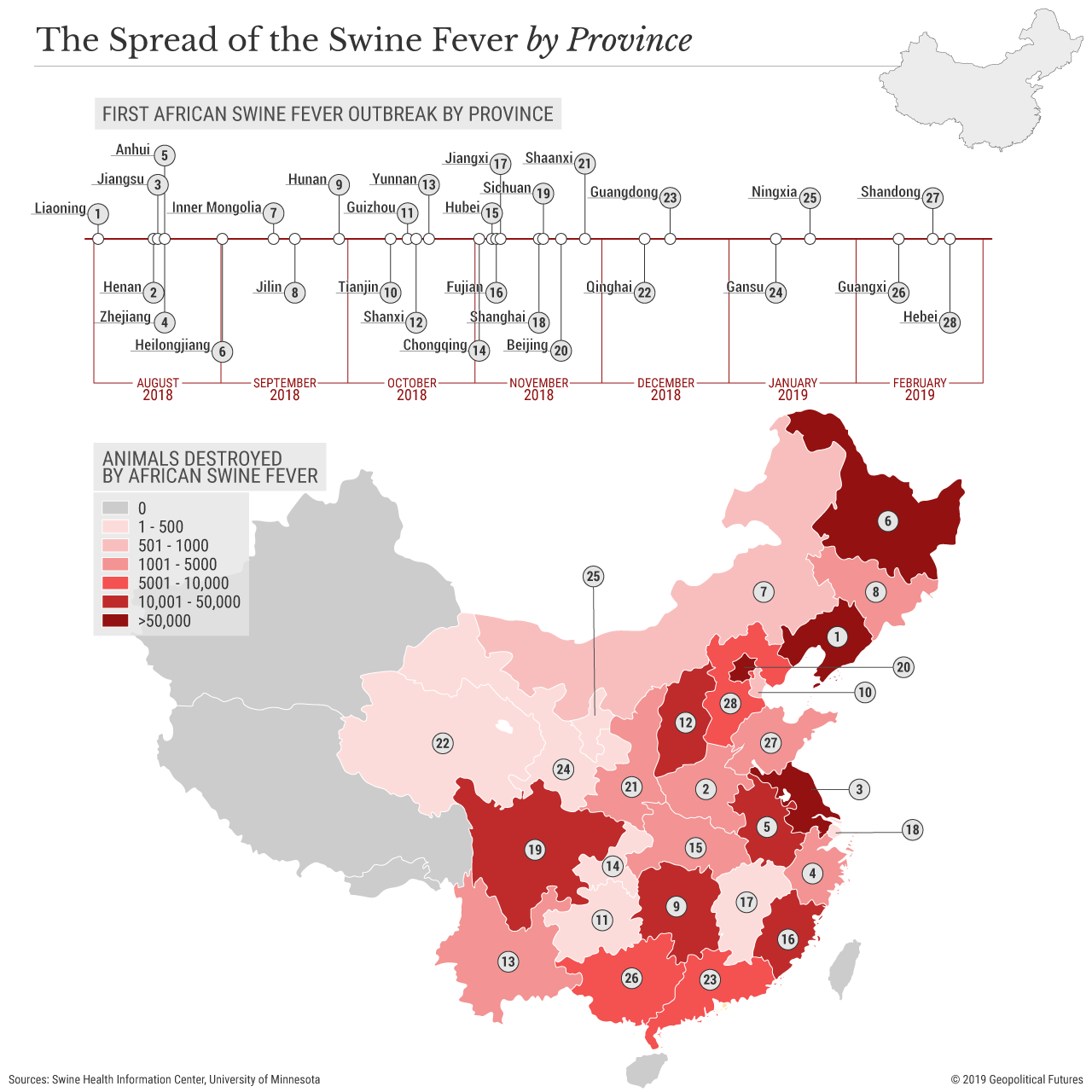

China’s African swine fever epidemic has entered its ninth month, and it shows no signs of abating. China reported new cases in three regions last month, as the disease continues to prove resistant to even the mighty Chinese government’s containment directives in regions as far flung as Hubei and Tibet. The outbreak has wreaked havoc on the country’s $128 billion pork industry and spread to nearby countries like Cambodia, Vietnam and Mongolia. As Japan, South Korea and Taiwan tighten customs controls at their borders, and as pig farmers elsewhere, especially in Brazil and the United States, see increases in pork exports (up 23 and 5 percent respectively this year), it is becoming clear that China’s ASF problem will have global ramifications.

The Pitfalls of Small-Scale Farming

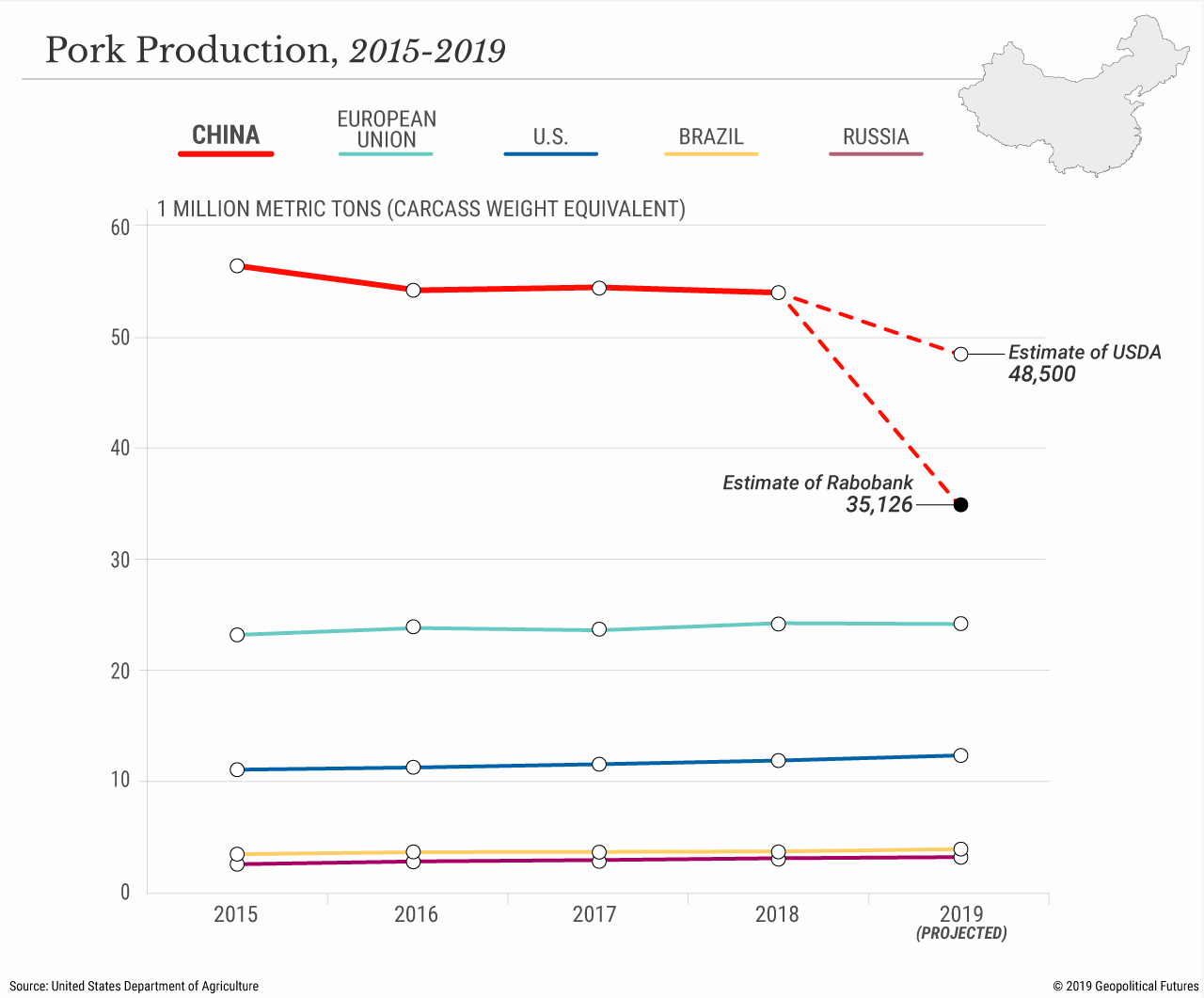

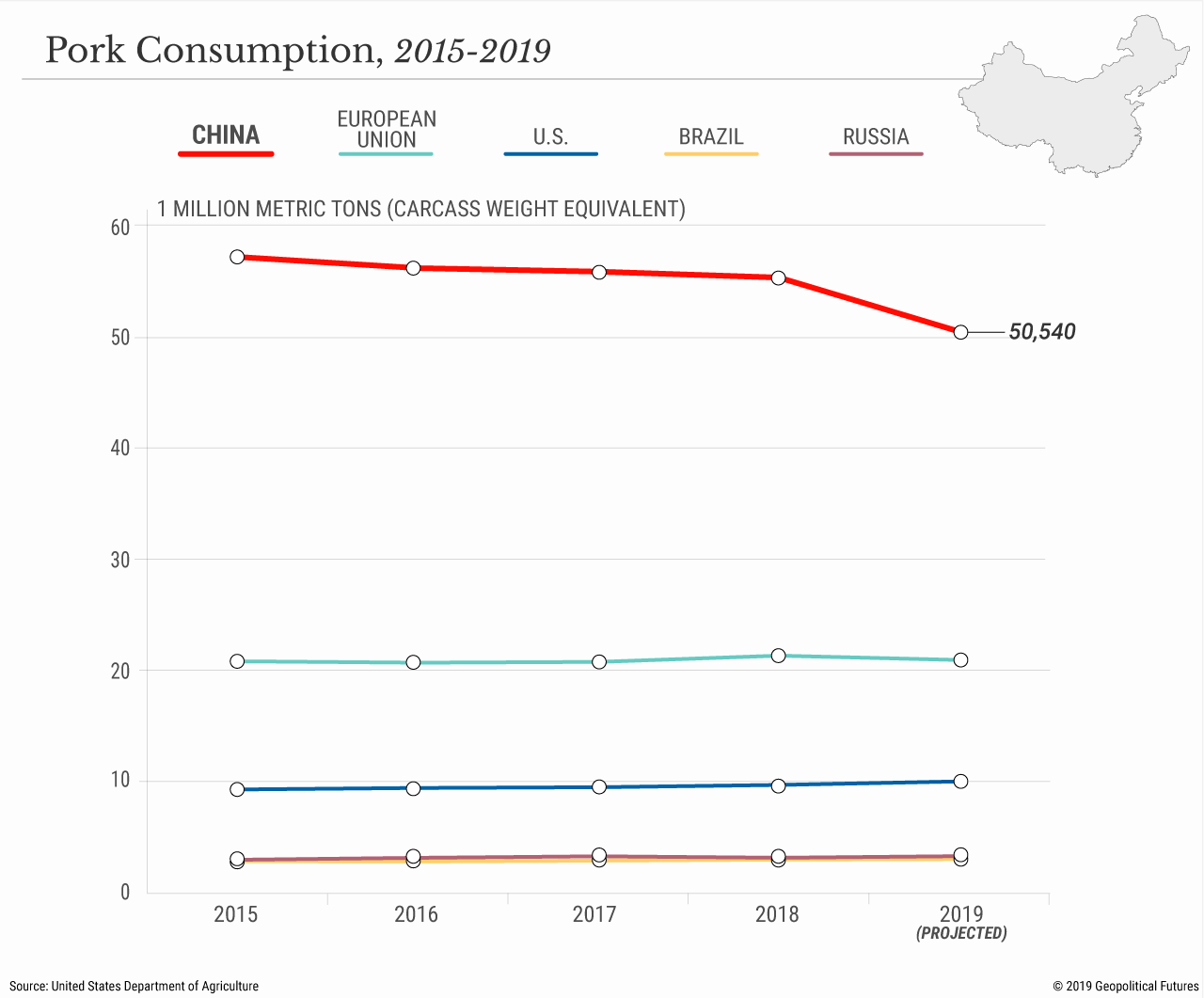

As with just about anything in China, the lack of reliable data makes it hard to know exactly what’s going on. The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that pork production in China, which produced roughly 48 percent of the world’s pork in 2018, will decline by roughly 10 percent in 2019 because of the epidemic. Rabobank, a Dutch financial services company that focuses on food and agriculture financing, is far more pessimistic. One Rabobank senior analyst recently estimated that Chinese production will drop by a whopping 35 percent, or almost 19 million metric tons – nearly double the United States’ total annual production. And that doesn’t even account for the inevitable decline in production in other countries like Vietnam – the world’s sixth largest producer.

It’s hard to dispute Rabobank’s pessimistic view, especially considering the structure of the Chinese pork industry. Unlike in the United States, where industrial farming led to a 70 percent drop in the number of hog farms between 1991 and 2009, the Chinese pork industry is still dominated by small farms. The data is somewhat hazy, but it all paints a similar picture. A March 2018 Reuters report found that over half of China’s almost 700 million pigs were produced on family farms. And a recent University of Pennsylvania study estimated that 98 percent of farms in China had fewer than 50 animals, which together accounted for almost a third of Chinese pork production. By comparison, in the U.S., 95 percent of all pork is produced by less than 10 percent of swine farms. While the number of small farms in China may be declining – Rabobank estimated before the outbreak that the share of pork produced by farms with fewer than 500 pigs would decline to 30 percent by 2020 – the industry is still heavily dependent on small-scale production.

Large-scale farming has a number of pitfalls. Its environmental effects (a 2010 Chinese government study found that agriculture was a bigger source of pollution in the country than industry), the often obscene conditions in which animals are raised and slaughtered, and the profligate use of antibiotics and the attendant rise of resistant bacteria all raise serious concerns. But when it comes to containing outbreaks, there are advantages to large-scale production. Russia learned this lesson the hard way when it experienced its own ASF epidemic back in 2007. According to Russia’s National Pig Farmers Union, before the epidemic, half of Russia’s pork output came from household farms. The epidemic all but wiped out these producers while production on industrial pig farms surged. Russia is now the fifth-largest pork producer in the world, and production this year will likely more than double 2007 levels.

The Chinese government has encouraged the consolidation of agricultural firms in recent years, as large-scale commercial operations and specialized household production increase their share in the pork industry. But it hasn’t been enough to prevent the ASF epidemic. Small-scale pork production in China is still significant and spread out throughout the entire country. Nine months into the epidemic, China has reported more than 100 outbreaks involving every single Chinese province. China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs devised a plan in February to divide hog production in the country into five distinct zones and to ban the shipment of pigs and feed out of infected provinces, but the disease continues to spread, even to larger farming operations with higher prevention standards.

Ineffective Response

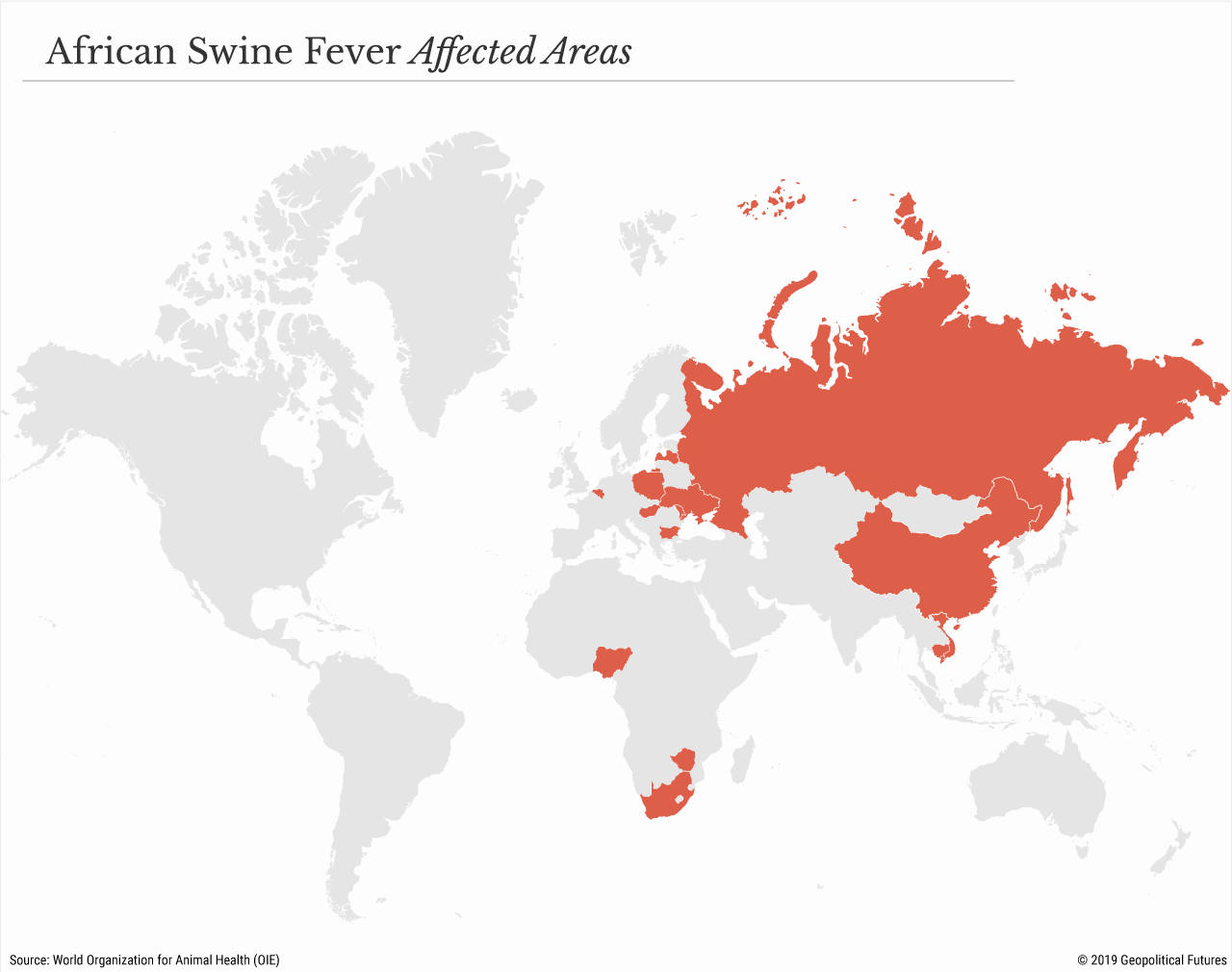

That’s arguably the bigger story here. All countries are susceptible to livestock epidemics. According to China’s Academy of Military Medical Sciences, the strain of ASF causing the current outbreak originated in Georgia and spread across Eurasia, from Estonia and Russia. Indeed, considering how easily ASF can be transmitted, it is remarkable infections have not yet been reported in the United States and other major pork-producing countries. But the real problem in China has been its ineffective response. Chinese efforts to quarantine the disease have thus far failed. The Chinese Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs hoped the south-central region, comprising Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi and Hainan provinces, would be the model upon which its new control system would be based, but infections in this region have actually increased since the measures were announced in February. Meanwhile, the government in Beijing has urged rural officials to offer new subsidies to pig farmers, including small producers, to scale up production, suggesting China is more worried about making up for the more than 1 million pigs that have been culled than containing the disease.

But stemming the spread of ASF is only one of China’s many concerns. It needs to contain the outbreak without setting off a social crisis in the country – and that is easier said than done. Meat, especially pork, is highly symbolic in Chinese society. President Xi Jinping, who himself lived through the Cultural Revolution and the associated periods of food rationing and Communist mismanagement of Chinese agriculture, knows from personal experience that the consumption of meat in modern China is a symbol of progress and prosperity. Under Xi, the Chinese government has tried to change such perceptions. In 2016, China’s Health Ministry released a set of dietary guidelines that would cut Chinese meat consumption by 50 percent. But such changes don’t happen overnight. In fact, China’s meat consumption has actually skyrocketed in the past 40 years. Since 1978, per capita meat consumption has quadrupled, and total meat consumption has increased tenfold.

In this sense, the ASF epidemic puts the Chinese government in an extremely difficult situation. To offset production losses from the outbreak, China will have to import more pork than it had planned to – making its negotiating position in trade talks with the United States, an important supplier of pork to China, even more difficult. Based on China’s track record thus far and the various pressures on the government in Beijing, it seems fair to say that China’s ASF epidemic is far from over and that it will take the country at least a few years to recover once it can finally get the spread of the disease under control. For pork producers in countries like Russia, the United States and Brazil, therefore, the Chinese outbreak could mean a boost in sales. Poultry and beef producers may also see bumps in Chinese imports as pork production and consumption decline. Pork consumption in China has already decreased 10 percent compared to the same period last year, while beef consumption is up 4 percent and chicken consumption is up roughly 10 percent. Still, there are risks for non-Chinese pork producers as well. A joint report released in April by the University of Minnesota and the Swine Health Information Center concluded that the risk of the ASF virus spreading to the U.S. has increased by 183 percent. In fact, U.S. Customs and Border Protection seized 1 million pounds of contraband Chinese pork at New Jersey’s Port Newark in March.

Contamination is a huge threat because there are multiple potential vectors of infection, from processed pork to animal feed to dust on farmers’ shoes and clothing. ASF is highly contagious and no vaccine has been developed, though the crisis has led to Chinese investment in research to discover one. The disease is also not just a Chinese problem: According to the World Organization for Animal Health, there are active ASF infections in South Africa, Ukraine, Poland, Hungary and numerous other countries. The Swine Disease Global Surveillance Project recently estimated that an ASF epidemic in the U.S. could cost the industry $10 billion in the first year alone. China raises almost half the world’s hogs and the pork trade is a highly globalized industry, suggesting it’s a matter of when, not if, ASF will be spread to more continents.

Indeed, the U.S. pork industry is beginning to take pre-emptive measures. Last month, the National Pork Producers Council canceled its annual World Pork Expo in Iowa to prevent participants from infected countries from bring the disease into the U.S. Just last week, the U.S. Grains Council updated its biosecurity protocols, restricting its teams from visiting swine farms and operations in the United States this year.

Regardless of how far the contagion will spread, China’s pork industry has some very difficult years ahead, and the Chinese Communist Party has yet another serious challenge to try to manage without setting off a wave of social discontent. China will likely muddle through this crisis, much as Russia did, and the end result will be a far more hygienic, consolidated and self-sufficient pork industry, but that is years, and perhaps even a decade, away. In the meantime, global pork producers that can shield their supplies from ASF stand to make decent profits, and companies in top beef- and poultry-exporting nations like Brazil, Australia, New Zealand, Argentina and the United States all stand to gain as well.