By Xander Snyder

The central question in Turkey’s invasion of Afrin has been whether it is a limited operation that will stop in northwestern Syria, or the first stage of what will become deeper Turkish involvement in the Middle East. Given that Turkey is intent on clearing the threat from its border, and that Kurdish forces extend far beyond the northwestern enclave of Afrin, there’s little reason to think that Turkey will stop after subduing Afrin.

There is, however, another threat that is forcing Turkey to take foreign military action: Iran. One of Turkey’s greatest historical adversaries, Iran has emerged from the Syria conflict in a relatively powerful position. One aspect of its qualified success has been the ability of the Bashar Assad regime, with Iran’s backing, to hold onto power and reconquer much of the territory it had lost in the civil war. Turkey sees a pro-Iran, Assad-led Syria on its border as a direct threat, which is why it looked the other way earlier in the war when Islamic State recruits crossed the border from Turkey to fight Assad.

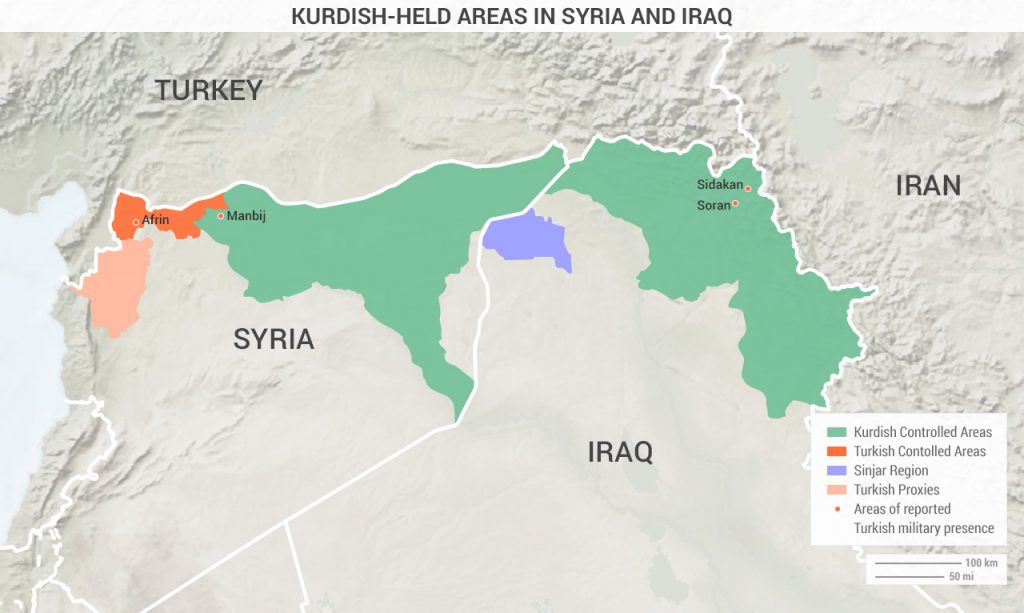

In response to Iran’s strong presence in Syria, Turkey wants to put pressure on Iran much closer to Iran’s own borders, in Iraq. Though Kurdish militias there do exist, Turkey is nevertheless using the presence of the Kurdish PKK in Iraq’s Sinjar province as a justification for intervention in Iraq. Iran, after all, has been able to significantly increase its degree of influence in Iraq in the past four years, a worrying trend for Turkey. Even as Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan threatens to launch a surprise invasion of Sinjar, Turkey has already begun establishing a greater military force in Iraq, with reports of Turkish soldiers parachuting into the village of Soran and reinforcing its presence in Sidakan.

A Turkish presence in Iraq does three things. First, it threatens Iran close to home, just as a pro-Iran Syria threatens Turkey, without risking direct confrontation. Second, it aims to counter the threat of pro-Iran militias in Iraq with additional firepower. Finally, it places Turkish troops on both sides of Kurdish-controlled Syria, which could set Turkey up for a two-sided offensive against the rest of the land held by the Syrian Kurdish YPG militia along Turkey’s southern border.

Shrinking Window of Opportunity

In Syria, with Iran’s financial and military assistance and Russia’s air support, Assad has been able to turn the tide and, for now, looks to be on the winning side of the war. If Turkey is to prevent the development of a strong, pro-Iran Syria, it needs to act. But as Assad continues to retake territory throughout the country, Turkey’s window of opportunity is closing.

Turkey’s shrinking timetable is why Erdogan – despite his incessant, mostly empty public pronouncements of forthcoming military action – must at this point be taken seriously when he threatens to assault Manbij, which is just east of the territory in Syria controlled by Turkey, and Sinjar in Iraq. Despite some token resistance from fleeing YPG forces, Afrin has fallen and is in Turkish hands. (Turkey has employed both its own army and Turkish proxies in its invasion of Afrin.) Most of its population has fled, clearing the way for the Turkish strategy to repopulate its border regions in Syria with Turkey-friendly, Sunni neighbors.

Turkey’s acquisition of Afrin, combined with the territory acquired in its 2016 invasion of northern Syria and territory held by Turkish proxies in Idlib, gives it near-contiguous control of the northwest of Syria with no adversary threatening its rear. Assad could deploy forces to the north to block Turkey’s advance, but this would require splitting his forces while he continues to struggle with rebels in key cities in central and southern Syria, such as Damascus and Homs.

With Afrin taken, the path to Manbij and greater control of its border with Syria is almost wide open for Turkey. Except, of course, for one major complication: the U.S. presence in northern Syria and its alliance with Kurdish militias.

Impasse in U.S.-Turkey Relations

Though the U.S. effectively greenlighted Turkey’s invasion of Afrin, it made clear that it would not withdraw its support from the Manbij-based Kurds. This is exactly what Turkey is demanding from the U.S.; Turkey sees no difference between Kurdish forces in Afrin and those in Manbij. For its part, the U.S. remains concerned about a resurgent Islamic State, which it was able to contain in part through its military cooperation with the YPG. This is no idle threat – while Kurdish forces were diverted from anti-IS operations to Afrin to combat Turkey, IS has been re-emerging and is again gaining control of territory.

This is the fundamental impasse in U.S.-Turkish relations. The U.S. needs a ground force to fight IS, and so far groups consisting primarily of Syrian Kurdish militias have been the only ones willing to follow U.S. orders. Yet it is those same Syrian Kurdish militias that Turkey feels it must eliminate to extinguish the threat along its border.

One of two things can happen: Either Turkey and the U.S. reach an agreement regarding Manbij and the Kurds, or they don’t. If they do, there will be some form of U.S. withdrawal from Syrian Kurdish territories. Turkey would enter provinces formerly occupied by the U.S. and its allies, with the blessing of the U.S., in exchange for agreeing to cooperate with the U.S. in its war against IS. In other words, another Kurdish group would be sold out by a former ally.

Such an arrangement would pose its own challenges to the United States. Unlike the Kurds, Turkey will be willing to cooperate with the U.S. only when it does not require subsuming its own interests in the process. And as the quagmire in northern Syria demonstrates, the U.S. and Turkey no longer find themselves consistently on the same side of the table. Turkey has also repeatedly shown itself willing to work with jihadists who would be distinctly unpalatable allies to the United States. Further, there is the risk that Turkey, harnessing the legacy of its Ottoman past to identify itself as the rightful heir to the caliphate, could even find ways to cooperate with IS or other such groups in an attempt to coalesce the disenfranchised Sunni Arab majority in Syria to further challenge Iran’s position there and in Iraq.

The other potential outcome, that Turkey and the U.S. do not reach agreement resulting in a withdrawal of U.S. forces from northern Syria, would severely constrain Turkey’s military option there. Though Turkey’s military is strong enough to defeat Kurdish militias in Afrin, it is not about to risk a conflagration with the United States. In this case, Turkey would be forced to pursue a near-term solution with Russia and Iran that allows it to cordon off the Kurdish corridor spanning northern Syria and Iraq, even if it is not through direct application of force. The proxy war would continue, but Turkey’s objective would still be the same: splitting off the U.S. from the Syrian Kurds and imposing Turkish, or at least pro-Turkish, control of the area.

Turkey would be extremely bitter about this eventuality, especially if Iran continues to improve its position in Syria, but it would probably not immediately break relations with the United States. After all, despite its ability to reach pragmatic tactical solutions with Russia, Turkish power has historically threatened Russia and will continue to do so as it grows stronger, making Russia a long-term adversary to Turkey. This was the strategic calculation that drove U.S.-Turkish cooperation during the Cold War, and it does not yet appear that Turkey is strong enough to take on Russian military power alone. In other words, if Turkey could not depend on the U.S., neither could it depend on Russia, which will force Turkey to balance cautiously between the two for the time being rather than sever relations with the U.S. outright. Even so, Turkey would not forget the slight. It would continue to accelerate the development of its domestic weapons industry so that it would no longer need to depend on the West’s protection from Russia.

Turkey’s invasion of Afrin represented a turning point in the Syrian war and its implications for the Middle East. Now that Turkey has conquered Afrin, U.S.-Turkish relations have reached a critical moment. Whether the U.S. and Turkey find a way to cooperate in northern Syria or not will substantially alter the regional balance of power, which in turn will shape how the major powers involved in the conflict – Russia, Iran, Turkey and the U.S. – craft their Middle Eastern strategy as well as their strategies in relation to one another. U.S.-Turkish relations, and the role that northern Syria plays in them, therefore have global implications spanning far beyond the region itself.