Originally produced on June 5, 2017 for Mauldin Economics, LLC

By George Friedman and Jacob L. Shapiro

Seventy years ago on June 5, US Secretary of State George Marshall gave a speech at Harvard University. Few speeches in modern times have had as much geopolitical consequence. In just eight paragraphs, Marshall made the case for significant US involvement in Europe’s economic reconstruction after World War II.

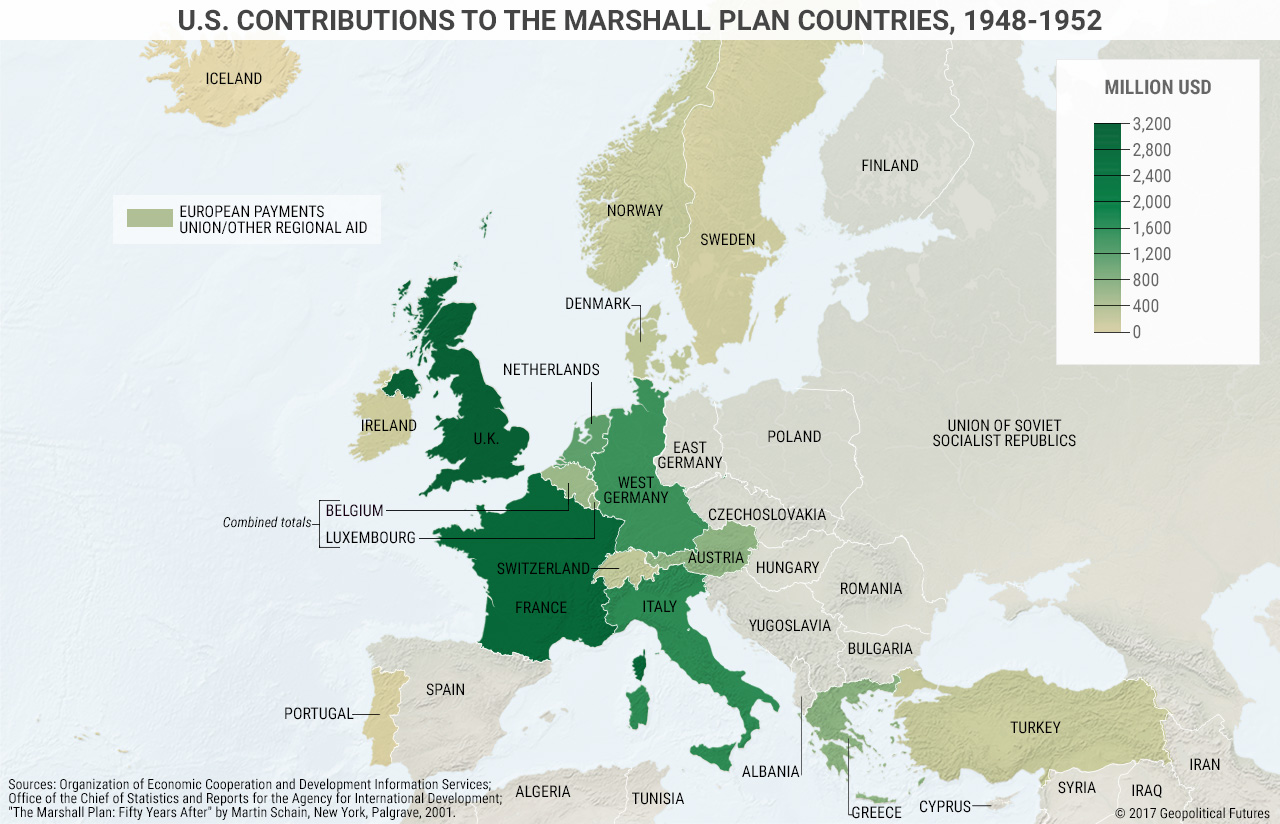

Within 10 months, the United States passed the Foreign Assistance Act of 1948. Better known as the Marshall Plan, it provided over $13 billion to 16 European countries (approximately $150 billion in 2017 dollars). According to the Congressional Research Service, the annual appropriation in 1949 alone accounted for 12% of the entire US federal budget.

The Marshall Plan became a significant instrument of American power. It represented a substantial sacrifice for the US, but one that paid dividends long after the US stopped providing funds to Marshall Plan recipients.

At a time when the world is divided on the merits of nationalism versus internationalism, it’s worth reflecting on why the Marshall Plan worked.

Strategy, Not Charity

Marshall made two key points in his speech to Harvard graduates. The first was the call for the rise of technocracy. Marshall said rebuilding Europe was a task of such “enormous complexity” that it had become difficult for “the man in the street” to make sense of the situation and what had to be done. His second point was that rebuilding Europe was in the United States’ economic interest. The return of “normal economic health in the world” was the precondition for political stability and peace. It couldn’t be offered piecemeal; it had to be backed by the full faith of the US government.

In effect, Marshall announced that the US was open for business. European countries heard the message and lined up.

By economic indicators, the Marshall Plan was a success. According to the Congressional Research Service, by the end of 1951, industrial production for participating countries had increased by 64%, and gross national product had risen by 25%. European countries set up entities like the Organization for European Economic Co-operation (which would later become the OECD) and the European Coal and Steel Community (the forerunner of the European Union).

But more important were the steps taken toward greater Western European integration. As Marshall said in his speech, at stake was a fundamental US interest: political stability and peace on the European continent. The Marshall Plan was not American charity; it was US strategy. Rebuilding Europe with US dollars and remaking it more in America’s image was the tactic the US used to achieve the strategic end of limiting the spread of Soviet power.

This was the heyday of what is now called liberal internationalism, a doctrine that argues for the intervention of international institutions to promote liberal values. The Marshall Plan is just one manifestation of the types of policies associated with liberal internationalism. The doctrine is most famously embodied in the United Nations, NATO, and the European Union. These are massive, well-known institutions—the faces, really, of liberal internationalism—but it shouldn’t be forgotten that they are made up of individual nations.

The United Nations was formed on the basis of the national sovereignty of its member states. This was the compromise embedded in the institutions the liberal internationalists created: Global bodies that used national power to promote liberalism throughout the world.

The Afterglow

But bureaucracy has a way of taking on a life of its own. After the fall of the Soviet Union, some international institutions saw an opportunity to take integration further. That the Cold War had been won seemed to validate their legitimacy.

There was, however, another interpretation: that the Soviet collapse meant the mission had been accomplished and that the extraordinary circumstances that had defined the post-World War II world were no more. The international institutions had served their purpose, and the world could finally return to state-to-state relations rather than concerning itself with alliances against a potential enemy.

These competing conceptions are straining the institutions that liberal internationalism dreamed up. US President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw the United States from the Paris climate agreement has dominated headlines in recent days. Before that, German Chancellor Angela Merkel suggested that Germany, and by extension, Europe, could no longer rely on the United States. Meanwhile, the disparate interests of EU member states have grown beyond Brussels’ ability to harmonize them.

This is not an unprecedented moment or a sign of the apocalypse. It’s the return of history. The US and Germany have different interests. Europe is a diverse continent of many different nations and has never been united under one banner. The US has resumed its traditional wariness of international agreements and suspicion of international obligations.

There is no Europe to rebuild, and there is no enemy to defeat. If George Marshall were speaking at Harvard’s 2017 commencement, he would be unable to find an issue to discuss that is as dire today as the need to reconstruct Europe was in 1947. There is no single issue today that requires America’s undivided attention, but rather several smaller issues that require America to divide its attention.

After World War II, Europe was beset with problems in search of solutions. It found the solutions in collaboration through newly minted international institutions. But these institutions have become solutions in search of problems.

On this June 5, then, it is useful to consider what made the Marshall Plan so successful. It was rooted in the national interests of all the countries involved. Its goals were clearly articulated. Its strategic interests were readily apparent. Its administration was focused, and its implementation well defined. There were mechanisms for accountability and enforcement. These are the things that must be considered when evaluating the strength and viability of an international institution or agreement in the future.