By Allison Fedirka

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte took office as an outspoken critic of U.S. military involvement in the Philippines. The two countries and their militaries have enjoyed positive relations for decades, but part of Duterte’s agenda has been to reduce the Philippines’ reliance on the United States and to work more closely with China. Yet when Islamist militants laid siege to Marawi – a city on Mindanao, the Philippines’ second-largest island – and Philippine security forces were unable to regain control in three weeks of fighting, it was the United States that Manila turned to for security assistance. The U.S. Embassy in Manila announced June 10 that U.S. special operations forces were assisting the Philippine armed forces in their operations in Marawi at the request of the host government.

GPF has discussed how the Philippines, despite its efforts to play the U.S. off China, is still heavily dependent on the United States. U.S. involvement in Marawi is solid evidence of that fact. But China is still interested in exerting greater influence in the Philippines, and the manner in which Duterte has accepted U.S. support leaves the door open for continued cooperation with the Chinese.

Caught by Surprise

The Philippine armed forces are no strangers to fighting domestic Islamist extremists, but they (and everyone else) underestimated the sophistication, size and preparedness of these particular fighters. One reason the attackers caught Manila by surprise is that they appear to be a convergence of several groups – not simply members of one group – all of which have sworn allegiance to the Islamic State. Estimates of the number of fighters from the outset include 250-300 from a group known as Maute; another 50-100 from a group led by a former leader of Abu Sayyaf (Abu Sayyaf was one of the Philippines’ most violent jihadist groups for nearly 30 years); 40 from either the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters or Ansar Khilafah Philippines; and 40 foreign fighters from Indonesia, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Morocco and Chechnya.

The assailants planned their attack on Marawi for some time. In fact, the Philippine military said the attackers’ original plan was to lay the groundwork for building a caliphate in the city. They had stockpiled food, weapons and ammunition in tunnels, basements, mosques and religious schools. They possess sophisticated weaponry, including sniper rifles and anti-tank weapons. They also had ample cash to finance their activities – security forces have uncovered $1.6 million so far. Their supply lines have reportedly been disrupted, but those fighting in the city still have supplies to last them several weeks or even a couple of months.

The attackers are well trained and demonstrate a firm understanding of strategy. They have made use of tunnels and underground facilities that can’t be easily destroyed. They also have demonstrated an intimate, masterful knowledge of the terrain and surroundings. They set up trained snipers in strategic positions throughout the city to deter military advancements. According to military commentary coming out of the country, they’ve even shown an awareness of the attack points for the military and know where to find cover or defensive positions.

Any Given Day

Manila’s failure to put down the attack shows that it lacks the technical capability to retake Marawi from such well-trained fighters, so it reached out quietly to the United States for assistance. U.S. forces are not engaged in the fighting – something Manila has been quick to point out – but the U.S. has shared intelligence, reconnaissance and surveillance information and has given Philippine marines four Gatling-style machine guns, 300 assault rifles and 100 grenade launchers.

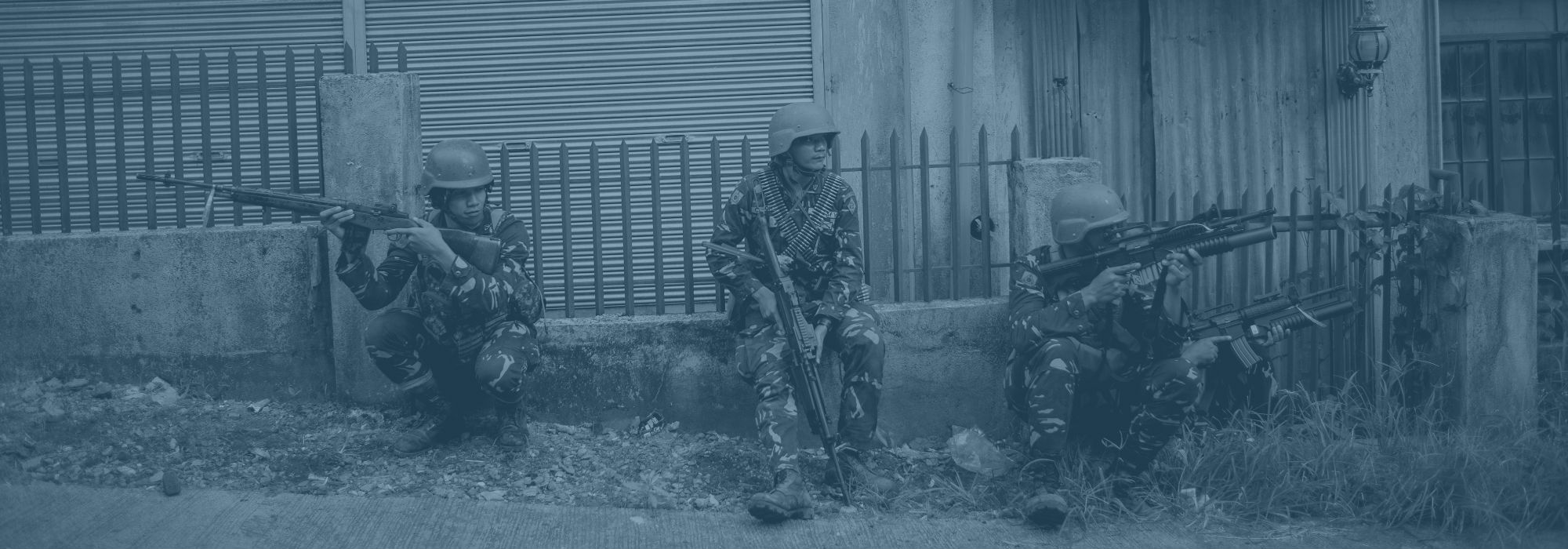

Philippine soldiers take positions during a mission to flush out Islamist militant snipers in Marawi, on the southern island of Mindanao, on June 6, 2017. NOEL CELIS/AFP/Getty Images

Philippine soldiers take positions during a mission to flush out Islamist militant snipers in Marawi, on the southern island of Mindanao, on June 6, 2017. NOEL CELIS/AFP/Getty Images

In seeking assistance, however, the Philippine government elevated Marawi from a domestic crisis to one that is tied to the balance of power in the region – particularly the competing interests of the U.S. and China in the Philippines. Not until the U.S. was involved did the Philippines make a general call for help from other foreign powers. The timing was deliberate. Manila knew the U.S. gave it the best chance to resolve the conflict, but it didn’t want to blatantly snub China or appear too close to the Americans. The Philippines knew China would not accept the invitation to step in – especially after the U.S. was already involved – but it saved face by extending the invitation. China’s Foreign Ministry issued a diplomatic response, noting that it recognized terrorism as a common enemy, reiterating its support for Duterte’s leadership and operations, and accepting “in principle” the involvement of other international players in the Philippines so long as Philippine sovereignty is respected.

But why didn’t the Philippines turn to China first? For starters, the United States’ expertise in counterterrorism and urban warfare is hard to beat. The U.S. and Philippine military also have years of experience working together, which greatly facilitated a fast response from the United States.

Second, if Manila were to invite the Chinese to help in a domestic security matter, it would set a dangerous precedent for the Philippines. China and the Philippines are engaged in territorial disputes over Scarborough Shoal and the Spratly Islands. Both sides remain steadfast in their claims because giving an inch would risk sacrificing territorial sovereignty. Inviting the Chinese military or security forces onto Philippine soil, however, would mean voluntarily offering China a powerful bargaining chip in the territorial disputes. The Philippines can’t rely on a foreign power for domestic security issues that also seeks to control disputed territory. The United States, on the other hand, is much farther away and has no designs on controlling Philippine territory; it is content to have influence.

Still, Duterte cannot appear too willing to accept U.S. security assistance. He has presented himself as a leader contemptuous of the imperialistic United States, someone who will protect the Philippines’ national interests by pursuing a foreign policy that involves more foreign partners. In truth, this is part of a strategy that allows Manila to play Washington and Beijing off one another as a way to get more concessions for itself.

To uphold his image, Duterte has sworn that he never asked the U.S. for assistance. The domestic security forces could have handled Marawi, he said, and only begrudgingly did he acknowledge and thank the U.S. for its help. The Philippine government and military have also emphasized that U.S. support is limited to technical issues and that no U.S. troops are actually participating in direct operations to retake the city.

There is, however, one other potential interpretation of events leading up to U.S. involvement in Marawi. Duterte and the Philippine defense establishment don’t always seem to be on the same page. Duterte will make an outlandish, headline-grabbing statement, and a defense official will make a follow-up statement that quietly walks back part of the president’s announcement. In fact, Duterte claims he didn’t approach the United States. If this is true – that the military reached out to Washington directly — it would underscore the precariousness of Duterte’s position.

Breaking the siege on Marawi will not eradicate the Islamist extremist threat in the Philippines. That said, the U.S. is one of the few countries with the ability to help reclaim the city. China is a virtual non-entity in international counterterrorism operations, an area the U.S. dominates, which gives Washington leverage over Manila. The Philippines still needs a closer relationship with the United States, regardless of what Duterte says on any given day.

The Geopolitics of the American President

The Geopolitics of the American President