By Kamran Bokhari

The annual multiday Islamic pilgrimage known as the hajj began Aug. 31. Each year, a few million Muslims from across the globe flock to Islam’s two holiest mosques, in Mecca and Medina, to perform their religious obligation. But the hajj is more than a religious pilgrimage; it’s an expression of Saudi power. Stewardship over the sacred mosques in Mecca and Medina, and thus the control of the hajj, gives the monarchy in Riyadh a legitimacy no other country that claims to be a leader of the Islamic world has, especially among Sunni Arabs. It is a source of stability at home and a foundation of its regional influence, and, as with most sources of power, Saudi Arabia won’t surrender it easily, even as it is contested in the coming years.

A Holy Responsibility

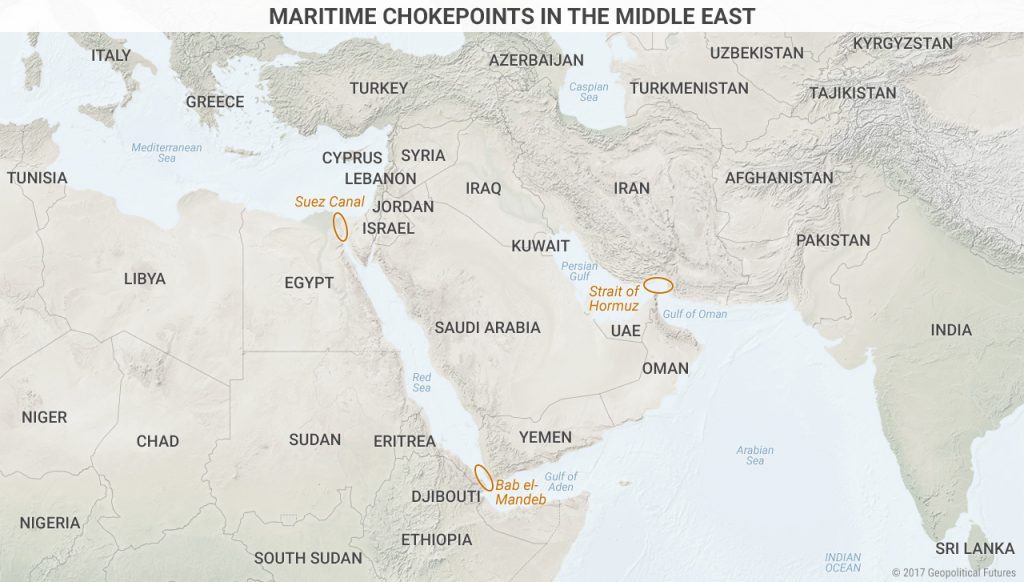

Any power that seeks to dominate the Middle East has to control the Hejaz region in the western part of the Arabian Peninsula along the Red Sea coast. From here, trade is possible north through the Suez Canal and south through the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. The area, the crown jewels of which are Mecca and Medina, changed hands numerous times over the centuries. The last time was in 1927, when Hejaz fell to the founder of the modern Saudi kingdom and father of the reigning monarch, Abdulaziz bin Abdulrehman. Abdulaziz had been expanding his territory in the region for decades, but he knew that to be truly exceptional, his kingdom had to control Hejaz and the holy cities.

Ninety years later, the Saudis realize that they can’t take their control over Mecca and Medina for granted. Their reign pales against the more than 1,400-year history of Islam. And they recall how their forefathers, in an earlier attempt to gain control over the Arabian Peninsula during the 18th and 19th centuries, lost control of the two cities. In 1808, during the age of the so-called first Saudi state, they seized Mecca and Medina from the Ottoman Empire. But they were able to hold them for only eight years before the Ottomans, through their viceroy in Egypt, took them back.

The same fate may have awaited Abdulaziz were it not for the discovery of oil in Saudi Arabia in 1938. After that, Saudi Arabia quickly became the world’s largest exporter of crude, strengthening the foundation of the kingdom. But Saudi Arabia’s control of the hajj has not gone unchallenged, especially in more recent decades.

In 1979, renegade Salafists laid siege to the Grand Mosque in Mecca for several days. The incident was a shock for the Saudis and extremely embarrassing for a number of reasons. First, the attackers – several hundred gunmen – came from the Saudi religious establishment itself. They felt that the Saudis had betrayed the state’s Salafi creed. Second, Saudi security forces proved incapable of retaking the mosque complex on their own and required the involvement of French commandos.

Eight years later, during the 1987 hajj, several thousand Iranian pilgrims held a protest in the Grand Mosque in Mecca. Saudi security forces opened fire, killing some 400 people, mostly Iranian pilgrims. The Saudis mostly avoided serious backlash because of the sectarian divide and Iran’s stated expansionist goals at the time, which most Muslim countries opposed. Iranians boycotted the hajj for three years, but by 1991 the matter was resolved.

Losing Control

The Saudi state would not be what it is today – the region’s sole remaining Arab power – if it was not the custodian of the two holy mosques. But the geopolitical environment for the Saudis is rapidly changing. This year’s hajj comes at a time of growing instability in and around the Arabian Peninsula. For years, the Saudi kingdom has faced the challenge from Iran to the east as well as expanding jihadism in the north in Iraq and Syria and in the south in Yemen, where Riyadh is fighting its own war.

A dispute with Qatar over the past few months has added to the Saudis’ list of problems. The tiny emirate of Qatar, powered by its status as the world’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas, has pursued policies that the Saudis and their main regional ally, the United Arab Emirates, see as a threat to their interests. A coalition led by the Saudis and the UAE abruptly broke off diplomatic ties with the Qataris in June and have been trying to isolate Doha ever since, trying to bring it back into their fold. The blockade has created problems for Qatari citizens seeking to perform the hajj.

Muslim pilgrims gather at the Grand Mosque in the holy Saudi city of Mecca early on Aug. 30, 2017, during the annual hajj. KARIM SAHIB/AFP/Getty Images

Muslim pilgrims gather at the Grand Mosque in the holy Saudi city of Mecca early on Aug. 30, 2017, during the annual hajj. KARIM SAHIB/AFP/Getty Images

Matters came to a head when, on July 30, Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir denounced an alleged Qatari call to “internationalize” Mecca and Medina. After a meeting with his counterparts from the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt, al-Jubeir told reporters that Qatar’s request was “an aggressive act and a declaration of war against the kingdom.” Qatar, however, denies that it ever made the request.

Regardless, the outcry from Riyadh is in truth an expression of Saudi Arabia’s own insecurity. There are currently no serious attempts to internationalize Mecca and Medina. Although the majority of the Muslim world opposes the Saudi interpretation of the faith and the kingdom’s attempts to run the holy places in accordance with Salafism, Muslim countries have historically accepted the kingdom as the manager of the holy cities and the organizer of the hajj. Until this alleged Qatari statement, Iran – Saudi Arabia’s historical nemesis – was the only country to officially call for internationalization. Being a Shiite Islamic state, Iran doesn’t carry much weight in the majority Sunni Muslim world.

Still, there is a common theme among Muslims from all parts of the world who feel strongly that the Saudis should not use Mecca and Medina as political leverage. A great many who have performed the hajj will complain about the way the Saudis have managed the event and mistreated pilgrims. On many occasions, when stampedes have claimed the lives of pilgrims, the Saudis have been accused of mismanagement of the hajj in spite of their massive financial resources.

Now that the Saudis are in the middle of a financial crunch because of the decline in oil prices, managing the hajj and maintaining the two cities is even more critical. Depressed oil prices weaken the kingdom’s ability to maintain stability at a time of growing regional insecurity. This has obvious and serious implications for the millions of pilgrims coming to Saudi Arabia from around the world over the next few days.

In the event that Saudi authorities have a hard time dealing with domestic unrest and violence, the kingdom’s role as custodian of the two holy mosques will come into serious question. This is a risk not lost on the Saudis, which is why in October 2015, Mohammed bin Salman (the new crown prince) launched an initiative called the Islamic Military Alliance – a force composed of troops from various Islamic countries whose primary goal is to ensure the security of the holy places and, by extension, the kingdom. In other words, even two years ago the Saudis were anticipating problems that they may not be able to deal with alone. It is not impossible, therefore, that in the future military forces from other major Muslim states, such as Pakistan, Egypt or even Turkey, could be stationed in the area to at least ensure that the hajj is not disrupted. With this reliance on other Muslim countries comes an inadvertent threat to Saudi custodianship of the two holy mosques, but there may be nothing Riyadh can do about it.

The Geopolitics of the American President

The Geopolitics of the American President